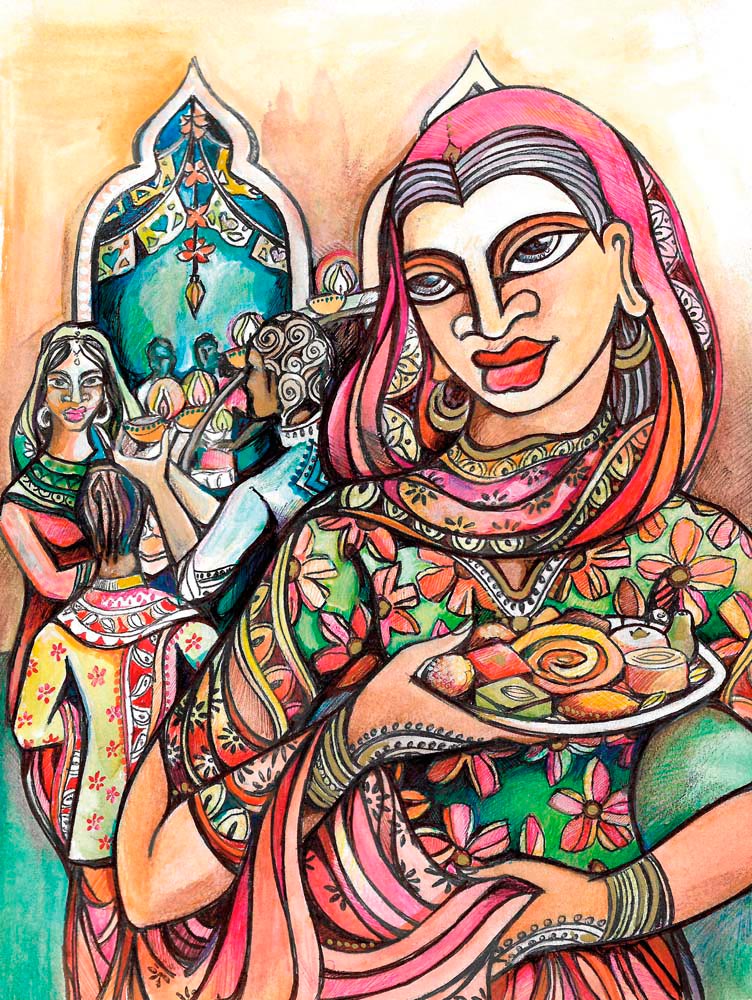

I always look forward to Divali, especially to enjoying the festivities with my good friend Roger and his family. They always welcome his rag-tag band of friends as if we were also relatives. His mother is an impeccable host, and she spares no effort to make sure we’re comfortable and well-fed. She’s also an awesome cook, and every year I look forward to her Divali menu: the curried vegetables and silky roti followed by a dessert of traditional Indian sweets like barfi, gulab jamun, peera, ladoo, and khurma.

With talk of Divali in the air — radio and newspaper adverts, deyas for sale in the markets, and gorgeous newspaper photos of Ramleela being re-enacted at grounds around Trinidad — I’ve been wondering about Divali food. If I had the opportunity to cook for Roger and his mom, for example, what would I prepare?

The Indian food we enjoy in the Caribbean is strongly influenced by North Indian traditions, as most of the Indians who came to the Caribbean were from Uttar Pradesh. So essentially we’ve become accustomed to one style of Indian food. The meal I’d cook would take influences from different parts of India — especially the sweets. For a greater appreciation of traditional and modern Indian cooking, my main point of reference is the London-based Indian chef Vivek Singh. I met Singh in 2007, and my first memory is of him giving me many samples from a booth manned by the team from his world-famous restaurant The Cinnamon Club. I’ve eaten at his restaurant several times, and through his many books and articles, he continues to inspire me.

In his book Curry: Classic and Contemporary, Singh starts by explaining that although curry is popular worldwide, he hardly came across the word in his old menus from India. In fact, his search for an “authentic definition” led Singh to travel through India to find out what curry meant to people there. In Mumbai, he said, there was a “palpable hesitation” from most people, and he saw only one reference to “curry” on the many menus he scoured. When Singh visited Bilaspur in Central India, most people thought his question was “absurd,” because you could “not group such a large variety of wonderful dishes under a single umbrella.”

And now for my ideal Divali menu. For starters, I would re-create Singh’s Punjabi chickpea fritters in yogurt curry, to pay homage to North India. His recipe is closest to the ones used in Uttar Pradesh. Pakoras are made from chopped onions, spinach, chillies, fresh coriander, fresh ginger, and other seasonings, with gram (chickpea) flour as the binding agent. The yogurt curry — yes, yogurt is amazing in curry — includes gram flour, turmeric, ghee, red chillies, cumin, fresh curry leaves, and lemon juice.

To take advantage of the great seafood found in Caribbean waters, the main course would be a kingfish curry. This particular recipe, nadan meen kootan, is from South India. Kingfish, as a robust fish, would go well with the combination of tamarind and coconut milk called for in the recipe. I’d serve this dish with our customary sides, like curried channa, bodi, pumpkin choka, basmati rice, and roti.

Now, what about dessert? While there’s always space for traditional sweetmeats, I want to take it to a different level. I have a chat with Singh via Skype about Indian sweets and their origins, as well as modern twists on the traditional.

He explains that at Divali, the goddess Lakshmi is venerated along with the elephant god Ganesh. “Lakshmi brings fortune, while Ganesh brings good luck, prosperity, and wisdom,” he explains.

And the sweet attributed to Ganesh is ladoo, made with chickpea flour. “You will find ladoo all over the country. People exchange boxes of ladoo. It is considered to be an auspicious dessert — it’s got a lovely warm golden colour from the chickpeas and the saffron.” Another traditional sweet is barfi, a fudge-like confection made from powdered milk. It is common in Trinidad as part of the typical bag of sweets distributed at Divali, and it’s so ubiquitous here that it’s unusual to hear Singh say that in India only families with “some means” actually make barfi. He notes there’s been some evolution to this dessert. “People are now adding pistachios and chocolate, and they’re also doing a kind of marzipan-type barfi to which cashews are added.”

Another alternative? “If you were down in the south of India, in Mysore or Bangalore, you’d encounter a sweet called Mysore Pak,” Singh says. “It is made out of chickpeas cooked down with sugar, ghee, and cardamom. Some baking soda is added so it can set like rock sugar.”

Singh also does special desserts for Divali in his restaurants. He makes the North Indian specialty halwa, described by food writer Felicity Cloake as “a sweet, buttery pudding made with everything from mung beans to pineapples, but which is often carrot-based,” and adds a twist. “I serve the traditional halwa inside a spring roll pastry, make it like a samosa. It’s deep fried, and we serve it hot with ice cream.”

This sounds like the kind of thing I would try. Halwa is pretty easy to make, and the ingredients are accessible. Singh’s recipe calls for evaporated milk, but some chefs use a mixture of whole milk and cream which gives the texture of a rich pudding. There’s also the option of adding fruit and nuts — almonds, pistachios, desiccated coconut, and raisins can all be used. I want to try some dried fruit, maybe some chopped dates that will soften and lend a great flavour and sweetness to the recipe. If you’re able to use different coloured carrots for the halwa, that would be perfect for presentation, and would create a dessert that gives a nice end to a satisfying meal.

I hope Roger and his mother would approve of my menu, which would look like this:

Punjabi chickpea fritters in yogurt curry

Kingfish curry served with pumpkin choka, curried bodi, and channa

Basmati rice

Paratha roti

Mixed green salad

Dessert

Carrot halwa spring rolls

Recipe: Carrot halwa spring rolls

Carrot halwa in its traditional form must be India’s most recognisable dessert, as it’s cooked in most Indian homes in winter. It’s a great dessert for Divali, and not very difficult to make.

60 g ghee or clarified butter

500 g regular carrots, peeled and grated

250 g black heritage carrots, peeled and grated

100 g sugar

2 tablespoons raisins

3 green cardamom pods, ground

250 ml evaporated milk

6 sheets of spring roll pastry (or filo pastry sheets)

30 g butter, melted, for brushing

vegetable oil, for frying

Divide the ghee between two separate pans and heat it up. Add the two different grated carrots to separate pans and sauté for ten minutes over a low heat until the juices from the carrots evaporate. Add half the sugar, raisins, and ground cardamom to each pan, and cook until the sugar melts. Divide the evaporated milk between the pans and cook until each mixture takes on the look and texture of fudge.

Spread the mixtures on two trays and let them cool. Divide each mixture into six equal parts.

Take a spring roll pastry sheet and brush the edges with melted butter. Place on a diagonal on a work surface. Place one heap of orange carrot fudge and one heap of black carrot fudge towards the corner closest to you. Take the same corner of the pastry, fold it over the carrot mixture, and continue rolling it until you reach almost to the middle of the strip.

Tuck in from both sides, then continue rolling until you reach the end of the pastry. Seal the edges with a drop of water. Repeat the same process with the remaining sheets.

Heat a deep pan of oil to 160° C and deep-fry the spring rolls for four to five minutes until they are golden brown. Drain on kitchen paper.

Serve hot with ice cream of your choice.

Serves six.

Recipe courtesy Vivek Singh, from Indian Festival Feasts