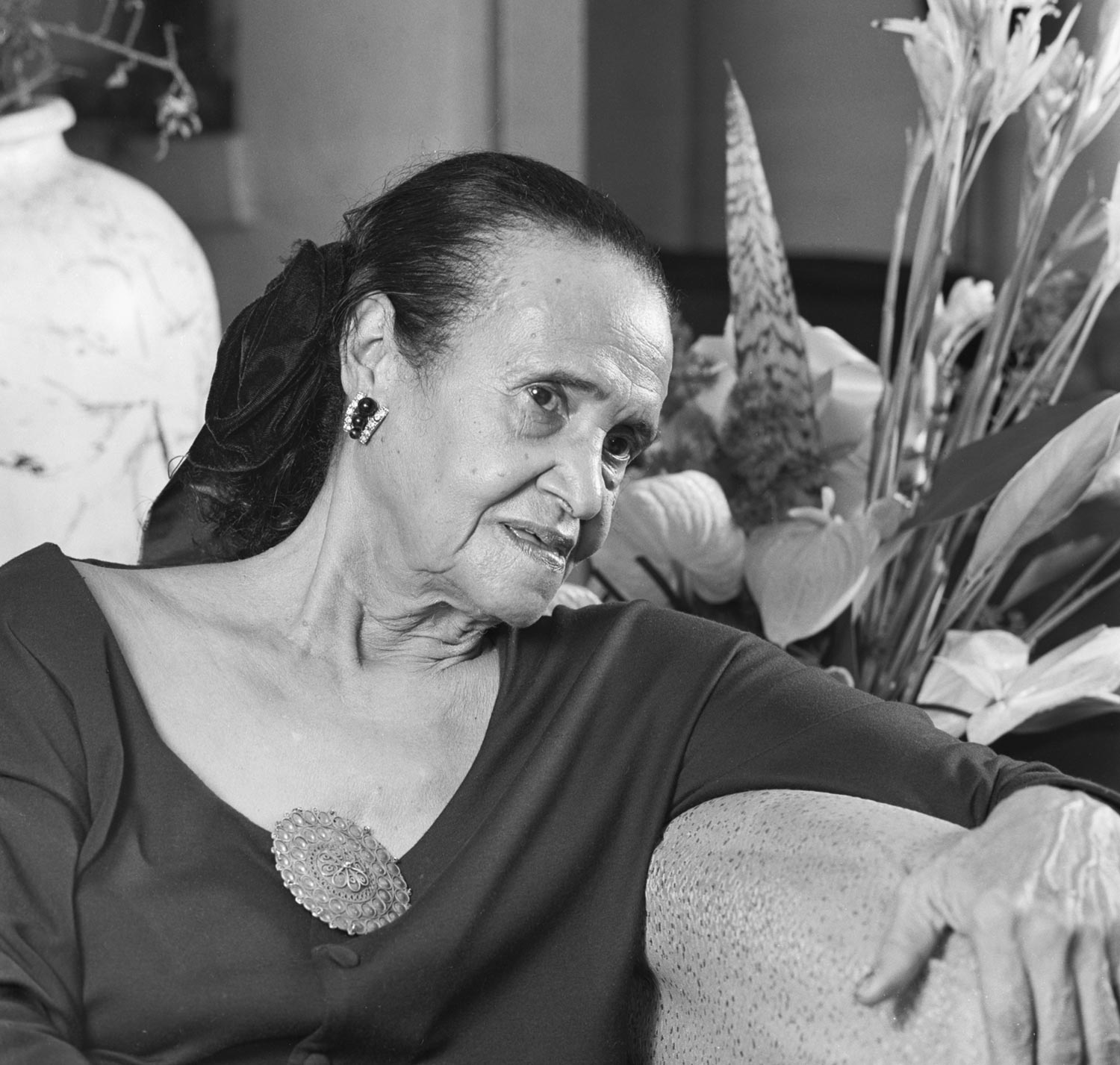

Last year, the brewers of Trinidad and Tobago’s best-known beer introduced a smaller-sized bottle. It immediately became known as a Beryl McBurnie, in a strange but logical tribute to the woman who is often called the grande dame of Caribbean dance.

The smaller beer, you see, was a Little Carib — and that’s also the name of Trinidad’s first theatre, established by Beryl McBurnie in 1948. The Little Carib Theatre is still indissolubly linked with McBurnie; and her name is legendary in the Caribbean performing arts. Almost 50 years after she founded the Little Carib, she is known as a pioneer in the preservation and — equally importantly — the appreciation of local art forms. Her honours include a national award and an OBE (Order of the British Empire). Molly Ahye, a former pupil and herself a leading dancer, has written a book about her (Cradle of Caribbean Dance: Beryl McBurnie and the Little Carib Theatre, Heritage Cultures, 1983). A local foundation for the arts gives scholarships in her name to practitioners of the arts.

McBurnie had a distinguished career as a dancer and choreographer as well as being the founder of the Little Carib. She has influenced and inspired dancers in her native Trinidad for decades; her example led Rex Nettleford to found the Jamaica National Dance Theatre Company, which has a world-class reputation, and in 1978 she was one of three pioneers in black dance to receive special tributes from the Alvin Alley Dance Company of New York.

But she also encouraged local musicians and other artists. André Tanker, whose music draws on folk traditions, recalls that it was at the Little Carib that he first heard the master drummer and Orisha priest Andrew Beddoe and began to understand the African roots of local music.

McBurnie was the first person to put a steelband on a stage – Invaders, who played at the opening of her theatre. Their panyard was within earshot of the Little Carib, in the middle-class district of Woodbrook, but in those days all steelbands were considered disreputable gangs of good-for-nothings, not real musicians. McBurnie, herself a natural rebel, was undeterred. She went so far as to choreograph a ballet, Jour Ouvert, to music by invaders’ leader Ellie Mannette. She bridged the gulf between theatre and Carnival: her theatre was the mas camp — the base — of Peter Minshall’s first Carnival band, Zodiac, in 1978.

The Little Carib and the work she did there inspired theatre practitioners to found “little theatres” throughout the Caribbean. And it was at the Little Carib that poet and Playwright Derek Walcott founded the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in 1959, 33 years before he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

As a performer, McBurnie could have been an international star. She worked professionally in the United States in the 1940s, after she finished her studies at Columbia University, under the stage name “La Belle Rosette”. She was, in the words of an enraptured English reviewer, “amusing, satirical, informative, occasionally naughty and altogether wonderful.” A New York reviewer wrote of a show she gave in 1942: “Rosette combined her abilities as dancer, interpretative artist and comedienne to great advantage. A year from now she’ll probably be one of Broadway’s great stars. She is different, definitely different.”

Part of McBurnie’s “difference” was in using West Indian dance, even then, at a time before independence when the West Indian islands were still attuned to colonial culture and indigenous forms were ignored or despised. The reviewer noted: “Her interpretations of folk songs and dances of the West Indian islands were masterpieces.” McBurnie’s work was always deeply rooted in the Caribbean, and it was to the Caribbean that she returned, giving up the bright lights, the fame and the money, to become a pioneer in the art she loved, and a mentor to countless others.

When she began, local dance was in danger of disappearing. Only European folk dance and ballet were being taught formally, and local dance was frowned on. It was thought primitive, insignificant. It wasn’t respectable. But McBurnie was convinced that dance was the most significant West Indian art form, since it contained the greatest variety of raw material.

“The question is,” she said in a lecture many years later, “are we prepared to accept what is originally ours, and not be afraid because it is simple and given to cottons and not silk? Or are we afraid because most of the vital expression of our folk material is of African origin?”

McBurnie was never afraid. She was always a showman — at eight she was reciting poetry in charity concert, and soon after that took to organising performances in the back yard of her parents’ home at 69 Roberts Street, where one day the Little Carib would stand. Young Beryl danced, played the piano and sang. At school she was taught the folk dances of Britain — the Highland Fling, the hornpipe. “I saw the irony of that,” she recalls. “I’m very interested in the classics; nothing can be more beautiful than Tristan und Isolde, nothing. But,” she goes on, impassioned, “you can’t give a little girl an aria from the Meistersingers to sing in a competition for her country when there’s a gallery of folk songs or even calypso, you can’t.”

McBurnie became a teacher after leaving school, and worked on school concerts, plays and operettas. In her free time she would go out into the country with folklorist Andrew Carr, who was researching local traditions.

This work was interrupted in 1938 when McBurnie’s father, a printer, took Beryl, the eldest of his four children, to New York to study medicine. She didn’t think it was a good idea. “I don’t have the organisation, the discipline,” she says. “That would be a straitjacket.”

She wanted to be a dancer, though her family thought it was a “terrible, terrible” idea.

But on the voyage to New York the ship’s captain took her side and persuaded her father to let Beryl study acting. Not that McBurnie had doubted that she would get her way. “I must do exactly as I want to do,” she says matter-of-factly. And it’s that determination, her indomitable will, which has helped her overcome innumerable obstacles — and which, turned to obstinacy, has also got her into trouble.

In New York she studied the arts and learned dance from Martha Graham. It was during a break from her studies that she returned home to stage her first major production, in 1940: A Trip through the Tropics. It was a great success. The Port of Spain Gazette reported: “Crowds were forced to return home due to the limited space in the theatre and with one voice, the public is clamouring for a repeat.”

McBurnie had catered for all tastes, including not only West Indian dances but also classical European music, and perhaps those not kindly disposed to local dance were nevertheless won over, like one critic, by the “ease, spontaneity and freshness” with which they were danced and by the “artistry and creativeness” of McBurnie’s work.

She returned to New York to continue her studies and to teach West Indian dance, leaving behind her a group which would be led by Boscoe Holder in her absence. Before she returned home in 1945 she told a New York reporter that she intended to found an academy for the arts in Trinidad.

Once back in Trinidad, McBurnie took a job as a dance instructor with the Education Department and introduced folk dance in the schools. The press reported approvingly: “Miss McBurnie is doing for these West Indies exactly what Diego Rivera did for Mexico when he rescued its artistic heritage in the graphic arts.”

Beryl once again took charge of her dance troupe, though she left them to travel to the Guianas, Suriname and Brazil to research dance. While in Cayenne she saw “a little intimate theatre”, which she sketched as a model for a theatre of her own.

The Little Carib Theatre was formally opened in November 1948. The foundation stone was laid by the great black American singer Paul Robeson, who was visiting Trinidad and whom McBurnie had known in New York. The programme included the limbo and bongo of Trinidad, the saramacca and djukas of Suriname, the Brazilian Terra Seca, as well as the original pieces Ah Passin, a “delightful market scene”, and Massala, “a witty aged East Indian’s dream of young love”. There was also Talking Drums, for which McBurnie had written the words:

Listen as they come across the plains,

like magic from the hills,

down the deep valleys,

bringing back a voice –Beryl McBurnie A voice that speaks of Africa!

Among the guests at the opening were government minister Albert Gomes and future Prime Minister Dr Eric Williams. As leaders of the nationalist movement in politics, both were long time supporters of McBurnie and her efforts. Gomes wrote of her: “It is Africa that is her inspiration; and the immediate fount from which she draws is the tradition of song and dance that persists tenaciously in Trinidad, despite all efforts to overlook or to besmirch it.”

McBurnie’s 1949 show Gems of the Little Carib, Williams thought, represented “the principle of self-expression by the West Indian people . . . the cause of the West Indian culture”

Unfortunately, support for the Little Carib from these quarters wasn’t given any more concrete expression. Aubrey Adams, a founder member of the Little Carib Dance Company, and later leader of his own company, remembers the first theatre as a shed made of sheets of galvanised iron and palm leaves. Costumes were equally basic: “We would use banana leaves or drape ourselves in a piece of cloth.”

The Little Carib wasn’t so much a building as an idea — a Big Idea, wrote the artist Wilson Minshall (father of designer Peter Minshall). “Those who know the Little Carib will appreciate the contrast between its physical structure and accessories … and the self-opening, expanding, inexhaustible, unfailing spirit of the place.”

McBurnie was the presiding genius. “Beryl inspired us all,” says Adams, still enough of a disciple to organise a show in honour of McBurnie, La Belle Rosette, to mark the Carib’s anniversary three years ago. “She lectured us on the arts, on morals, values. She had a library. She got her supporters to come and visit us.”

Molly Ahye, who followed McBurnie’s example and studied the performing arts, was a principal dancer with the Little Carib company from 1952 to 1965. “Beryl gave you the feeling that there was more to know. The love and passion for dance that I got motivated me to do deeper research.”

There was drumming and dancing every night at the Little Carib, plays and poetry readings and frequent performances. But McBurnie couldn’t always be there. “Beryl was always begging,” Ahye recalls. “Whatever we needed, Beryl had to get it.”

Luckily, McBurnie had great powers of persuasion. Ahye recalls: “I worked with BWIA, I had children, but I’d rehearse until one in the morning, I danced while I was pregnant… Beryl could get you to do anything.”

But it wasn’t easy, for all McBurnie’s charm and energy. She was an artist, not a businesswoman or a bureaucrat, and raising funds and organising were distractions from her vocation as a dancer and teacher. The Little Carib suffered because she had to spread herself so thin.

Besides, the dancers were amateurs — you couldn’t make a living as a dancer in Trinidad — and rehearsals had to be fitted in whenever the demands of their jobs permitted. Aubrey Adams remembers how embarrassed he was when McBurnie came to the government office where he was a young clerk, and persuaded him to rehearse for a show in his lunch hour — on the spot. The other clerks watched, while McBurnie, unfazed, beat time on a desk.

In 1957 McBurnie, accompanied by some of her dancers, went to teach at a summer school in the arts at what was then the University College of the West Indies in Jamaica. One of the participants was a young St Lucian writer called Derek Walcott, who saw in McBurnie’s work the possibility of using folk material to create genuine West Indian theatre. His Ti-Jean and His Brothers, which is based on St Lucian folklore and incorporates song, dance and dialect, was written shortly after this encounter.

By 1959 Walcott had moved to Trinidad and was holding weekly theatre workshops at the Little Carib. The Little Carib Theatre Workshop gave its first public performances in 1962, and Walcott wrote in the programme that the company hoped to inspire the same “interest in drama as there is in dance at this theatre, and is experimenting with the possibilities of fusing the two into an indigenous West Indian form”.

But McBurnie wanted her theatre reserved primarily for dance, and the Theatre Workshop’s stay was a stormy one, with dramatic clashes between the two powerful personalities of McBurnie and Walcott. More than once the actors arrived for rehearsals only to find that McBurnie had locked them out. The eventual split had unfortunate long-term consequences for both groups: since then the Trinidad Theatre Workshop has had no permanent home, and for more than a decade, the Little Carib has had no resident company in either dance or drama.

The Little Carib Theatre still stands on the corner of White and Roberts Street in Woodbrook. It’s still used for shows, and it’s still small, cramped and ramshackle. Sometimes you have to strain to hear above the barking of a dog in the street outside or the sound of Invaders practising in their panyard around the corner.

But the Little Carib remains what it always was, a Big Idea, and that has spread far and wide. Dance companies build on the foundation that McBurnie laid, rooting their work in the fertile Caribbean earth. The folk dances that were in danger of being lost when McBurnie began her work are now carefully preserved and proudly displayed by companies like the 80-strong Malick Folk Performers, who tour the region and beyond, as well as performing in the Best Village Competition, which involves folk dance and drama groups from all over Trinidad and Tobago. More avant-garde dance companies whose origins can be traced back to McBurnie’s pioneers produce work that combines the folk and the modern.

As for McBurnie, she’s still a trouper. Dramatically gowned in scarlet or black, hat tipped rakishly over one eye, she turns out for performances and exhibitions by fellow artists — she knows them all — sometimes even working to promote their efforts. Last year during Carifesta, the Caribbean arts festival, staged in Trinidad, she held a reception in honour of Rex Nettleford. The guest list was a who’s who of Caribbean artists, from Walcott to Minshall to musician and artist Pat Bishop, novelists Earl Lovelace and Lawrence Scott; and every one acknowledged a debt to McBurnie.

Paying tribute to her on behalf of Caribbean artists a few years ago, Rex Nettleford spoke of her “creole fire and burning enthusiasm of the possessed artist and visionary”.

In her seventies, McBurnie has that fire and enthusiasm still. Asked what keeps her so busy, she’s surprised at the question. “The life itself,” she replies. “You have to keep pushing and prodding, you have to keep nourishing it — it’s like watering a plant. You have to keep at it, because as you get careless the weeds take over.”