Dr Jones

In her memoirs, published with the title I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, Grace Jones writes: “Trends come along and people say, ‘Follow that trend.’ There’s a lot of that around at the moment: ‘Be like Sasha Fierce [Beyoncé]. Be like Miley Cyrus. Be like Rihanna. Be like Lady Gaga. Be like Rita Ora and Sia. Be like Madonna.’ I cannot be like them — except to the extent that they are already being like me.”

Indeed, these contemporary cultural icons are all — consciously or unknowingly — following the woman who has rocked the music world to its very foundations with her inimitable style, husky voice, and boundless audacity over the last forty years. “I have been so copied by those people who have made fortunes that people assume I am that rich,” Jones writes. “But I did things for the excitement, the dare, the fact that it was new — not for the money, and too many times I was the first, not the beneficiary.”

Of course, she would have to be Jamaican. In her biographical film Bloodlight and Bami, released in 2017, Jones’s Jamaicanness is clearly one of the secrets to her success — manifested in the awesome physicality that makes her performances so hypnotic (she still works out daily, lifting weights), the scathing yet playful wit, and the absolute disdain for pretension. No other culture could have produced a force so defiant, and revolutionary, as Grace Jones. “Bloodlight” refers to the red light in the studio that is switched on when an artiste is recording, and “Bami” is the popular Jamaican bread made from cassava. The title alone lets us know how profoundly Jamaica has shaped Grace Jones.

In the film, she returns home for a family reunion which includes her brother, a well-known pastor in Los Angeles. We discover the source of much of her angst — a childhood peppered with licks and repression, exposure to a fundamentalist religiosity by her grandmother’s partner that she would later channel on stage, mimicking his mannerisms and way of speaking — exorcising her demons, as it were.

After the screening of Bloodlight and Bami in Kingston last year, Jones took part in a question-and-answer session with the literary and cultural scholar Carolyn Cooper, founder of the Reggae Studies Unit at the University of the West Indies. It was Cooper who proposed that Jones be conferred with an honorary doctorate at this year’s graduation ceremony. It’s more than fitting that UWI should honour Jones. Both born as British colonial subjects, they came of age in the early 60s with the independence movement, entering a phase of radicalism in the 70s that changed the way the people of these islands saw themselves, and gave them a newfound sense of identity and confidence.

“The film is inspiring,” says Cooper, “because it shows her as this diva, the Grace Jones persona, but also as an ordinary Jamaican girl, who had a sense of style from she was young, who had to fight against the religious conservatism of the family and just say, Hell no! I’m not going to be limited by people’s definition of who I should be — and she just buss out!”

Born on 19 May, 1948, in Spanish Town, the first capital of Jamaica (and also the birthplace of roots revival artiste Chronixx and sprinter Yohan Blake), the seemingly ordinary girl who was brought up in a strict and extremely religious household would channel all her repressed emotions and traumatic experiences into performances and videos that pushed all kinds of boundaries — of thought, beauty, expression, art, fashion, music, you name it, Grace Jones challenged it all.

She left Jamaica at the age of thirteen to join her parents in Syracuse, New York. By twenty, she had abandoned her attempt to become a Spanish teacher and instead became a fashion model — eventually dubbed “the ultimate fashion muse” by Vogue. Her dramatic bone structure and unapologetic androgyny made her a hit on the runway, adored by the likes of designers Yves Saint Laurent and Issey Miyake, and at once she was sought after as a model for big-name photographers Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin. From the moment she arrived in Paris in 1970, she became a member of the elite party crowd. In addition to sharing a flat with American actresses Jessica Lange and Jerry Hall — in Bloodlight and Bami she tells off a TV producer in impeccable French — she often tore up the dancefloor with the likes of designer Karl Lagerfeld.

Considered “a touchstone for designers in need of a muse to channel fearlessness, androgyny, and raw sex appeal,” Jones soon had a list of admirers including everyone from the Tunisian-French couturier and shoe designer Azzedine Alaïa to the Italian fashion designer Riccardo Tisci.

Jones’s statuesque flamboyance proved to be a hit in the New York City nightclub world, too — she was one of the most memorable characters to emerge from the infamous Studio 54 disco scene. An encounter with fellow Jamaican Chris Blackwell led to a recording contract with his Island Records in 1977, and the girl from Spanish Town moved from top model to pop star. She made the transition with an insouciant confidence that has not diminished in the slightest with time. While her first three albums — Portfolio, Fame, and Muse — weren’t commercial hits, gay men loved her. For her sexually charged live performances, she was dubbed “Queen of the Gay Discos.”

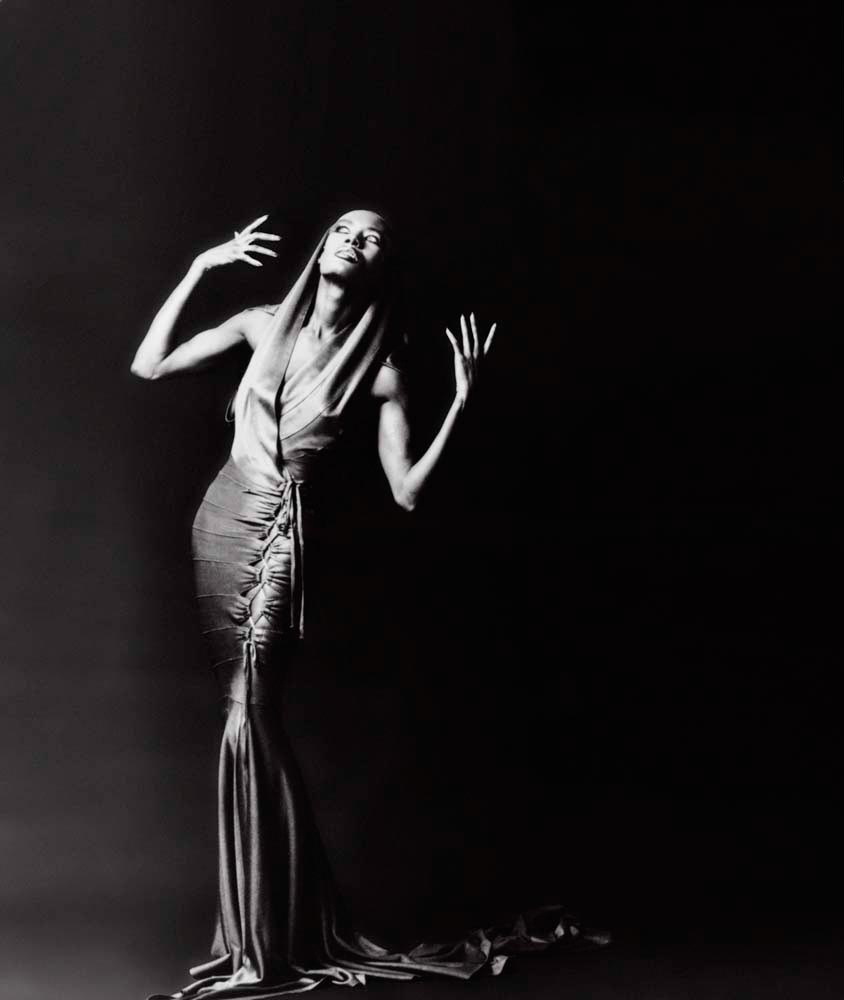

Her album covers were studies in and of themselves — the suit and cigarette on Nightclubbing, that nude arabesque on the cover of Island Life: they made you stop and think, and you never forgot them. She made the hooded scarf her own, and the geometric flat top was suddenly sexy on a woman. Then there was the body paint. Her Afrofuturist image and Cubist fashion, her close crop and dazzling makeup made her an instant icon.

The French photographer Jean-Paul Goude, her one-time partner, created some of the most iconic images of Jones. “I wanted to focus on Grace’s masculinity,” he recalls, “to use what other people thought an embarrassment, and turn it around to her advantage. I wanted to create — with her, of course — a new character. It went beyond just a haircut, it was an attitude. It was new and strong and ambiguous. You didn’t know if it was a man trying to be a girl or a girl trying to be a man. It was a revolution. I remember the A&R guys at Island [Records] saying, ‘Are you f—ing crazy? This is never going to work.’ And, of course, it did.”

“It made me look more abstract, less tied to a specific race or sex or tribe,” Jones has said. “I was black, but not black; woman, but not woman; American, but Jamaican; African, but science fiction.”

The 1980s and the end of the disco era led Jones to New Wave and more experimental work, including the albums Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing, produced by the “Riddim Twins” — Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare. This was also the decade when Jones would launch out into film, landing roles in Conan the Destroyer and the James Bond movie A View to a Kill. She was also a favourite with the tabloids, who were obsessed with her romantic involvement with Rocky IV star Dolph Lundgren.

In 1985, she unleashed Slave to the Rhythm and Island Life. The following year, Inside Story spawned one of her last successful singles, “I’m Not Perfect (But I’m Perfect for You).” After 1989’s Bulletproof Heart, Jones continued to record singles and collaborations with performers as diverse as operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti and rapper Lil’ Kim — but for almost two decades Jones released no new albums. Then came 2008’s Hurricane, “classic Jones,” according to one review, featuring a slew of guest performers. “This being Grace Jones,” wrote the music magazine Pitchfork, “she easily upstages her contingent of helpers. Indeed, Jones isn’t so much a singer as a force of nature, a black hole that pulls all attention right to its centre.”

But despite her undeniable diva status, and her elusiveness as a subject (“Grace only does press when she feels she has something new to say”, according to her agent), at home in Jamaica, she can be herself. “I immediately warmed to her,” recalls Carolyn Cooper. “She didn’t have the vibe I was expecting. You know, when you hear Grace Jones, you think she’ll be full of herself. But she was just cool. I admire that about her. She wasn’t caught up in the hype.”