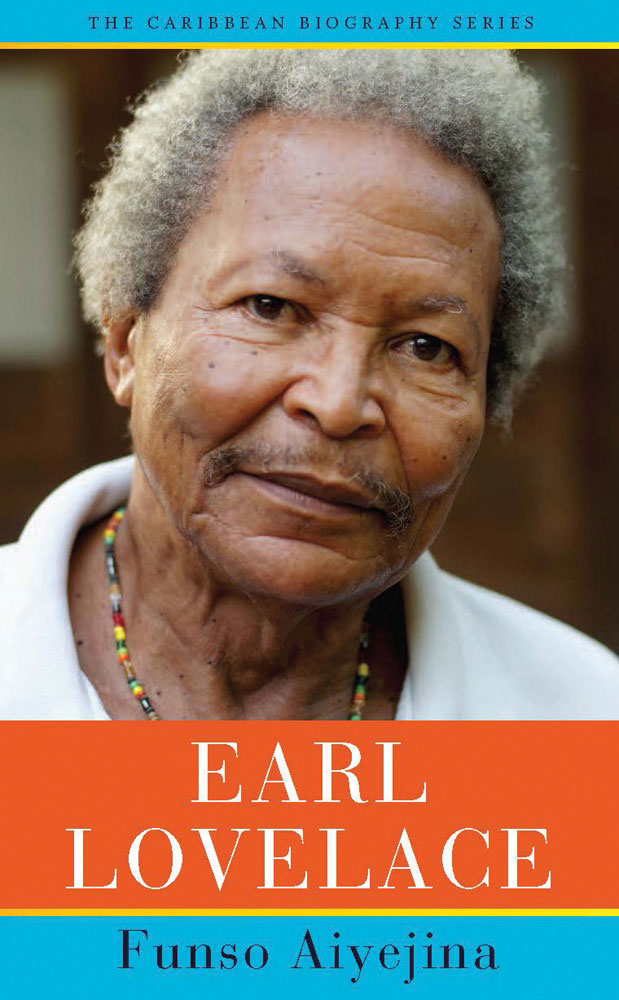

Earl Lovelace

by Funso Aiyejina (The University of the West Indies Press, 114 pp, ISBN 9789766406271)

Derek Walcott

by Edward Baugh (The University of the West Indies Press, 112 pp, ISBN 9789766406455)

Marcus Garvey

by Rupert Lewis (The University of the West Indies Press, 112 pp, ISBN 9789766406486)

Beryl McBurnie

by Judy Raymond (The University of the West Indies Press, 122 pp, ISBN 9789766406783)

Two writers, with a treasury of awards between them. The leader of the Pan-Africanism movement. The dancer who founded Trinidad’s Little Carib Theatre.

These are the first, often declarative statements that historians and schoolchildren alike can make of Earl Lovelace, Derek Walcott, Marcus Garvey, and Beryl McBurnie. The Caribbean Biography Series, undertaken by the University of the West Indies Press, considers the gaps of knowledge between these vast, sweeping definitions. The series, which pairs one Caribbean icon with one skilled biographer, pivots on an ambitiously practical axis, to serve multiple needs: these biographies are archival, instructive, crafted for maximum cultural resonance in clear, unpretentious tones.

To pore over, assemble, and present the structure of an extraordinary life requires an unflinchingness of vision and a discipline of focus in the biographer. In that regard, Aiyejina, Baugh, Lewis, and Raymond are committed curators of human experience. Lovelace, Walcott, Garvey, and McBurnie are served up with their laurels, and not without their attendant warts: their biographers are not intent on mounting hagiographies, and each book shines with the specificity of this nuanced, tempered devotion.

This is not a devotion of ardour, always: for these four biographers — themselves each eminently respected in their fields of academia and journalism — the focus, the intensity of reportage, is an activated attention in each work. See how Aiyejina reports from close quarters on his own relationship with Lovelace, marrying personal anecdote with information gleaned from hours of recorded interviews, immersion in formally housed archives, and the scrutiny of Lovelace’s manuscripts. Raymond, in constructing several complementary (if not always complimentary) images of Beryl McBurnie as she was — visionary, self-possessed, temperamental — transcribes the voices of other researchers and experts, producing an enriching myriad of perspectives on La Belle Rosette.

Garvey, ever the larger-than-life figure, is animated with a sensitive candour via Lewis, who works superlatively to bring “The Black Moses” within accessible reach: “Garvey had no illusions as to where his vision came from. In a reply to a Costa Rican evangelist who was his supporter and saw him as a prophet, he said his vision was based on the practical side of life.” As Aiyejina did with Lovelace, Baugh reaches deep into the caverns of Walcott’s writing, puzzling and working at its majesty of significances with a generosity that benefits the reader first. Everything is done for the benefit of the reader of these Caribbean Biographies, assuming nothing about who might pick up one of these slender, unassuming volumes: professional or dilettante.

Not only will you understand Lovelace, Walcott, Garvey, and McBurnie better, following these readings: you will be inspired to read their biographers, too.

Tentacle

by Rita Indiana, translated by Achy Obejas (And Other Stories, 160 pp, ISBN 9781911508342)

In this audacious, utterly necessary novel of the dangerous future, the Dominican Republic’s Rita Indiana gives us a dystopia bleeding just on the fringes of our worst — and wildest — imaginings. A trans sex worker of abusive origins, Acilde Figueroa is tasked with saving the fate of the planet’s ecologically distressed oceans, a feat which necessitates a trip through time itself. If this blistering, vertiginously intense prose sounds fanciful, elements of magical realism are layered in the exposition, but you’d be unwise to pass this off as a pale García Márquez knockoff. Losing none of its dark urgency in Obejas’s virtuosic translation, Indiana animates a future we must avoid, even as sea levels rise in warning.

Where There Are Monsters

by Breanne McIvor (Peepal Tree Press, 192 pp, ISBN 9781845234362)

In this shapeshifting debut, McIvor’s Trinidad is a land of secrets and concealments as old as the mountain ranges. These short stories not only show us what people are willing to do in the dark; they map (in)human complexity — and the psychology of finding oneself to be monstrous — in prose that pulls taut with the control of a nocked arrow. McIvor locates her storytelling targets repeatedly, with a carefulness that belies her certain talent: she writes of women and men made desperate and clumsy by love, of a centenarian cannibal matriarch, of a Midnight Robber turning macabre in the Botanic Gardens. That very Robber incants, convincingly, “Trinidad, I walk on water to you.”

Bookshelf Q&A

T&T born, US-based Krystal Sital’s memoir Secrets We Kept: Three Women of Trinidad (Norton, 352 pp, ISBN 9780393609264) has earned critical acclaim for its raw, unflinching unveiling of family trauma. Sital talks to Shivanee Ramlochan about writing into, and confronting, legacies of domestic violence in the Caribbean.

The women in Secrets We Kept are your family: was it uniquely challenging to access their stories?

Yes and no.

Yes, because I had to figure out just how to do it, and that was all trial and error. In one of my earlier attempts at figuring out how to nail the interviewing process, I tried recording my mother while we spoke. What a mess that was, because she kept staring at the recorder, even if I moved it from view, and then slipped into this pseudo-American accent that wasn’t how she spoke, no matter what world she was inhabiting at the time.

And no, because once their stories started to flow, they flooded. It was like me trying to contain the sea in a bowl.

In this memoir, you’ve renamed everyone but yourself. Tell us about this singular, genre-challenging choice.

I changed everyone’s names to protect their privacy and identities, but also because my lawyer advised that I do this so I wouldn’t get sued.

One of the things I hoped to accomplish with this book was stop the silencing of women’s voices, stories, and histories. To honour that, I entered into an agreement with my readers, and therefore I didn’t want to change my name or hide my identity. That, to me, would be another form of silencing myself, and I refused to do that.

Your book dismantles stereotypes of Indo-Caribbean trauma survivors. Which cliché was it most valuable for you to tackle?

That we are not actively breaking these cruel cycles of violence. From one generation to the next, these women were working against the cultural norm. My grandmother fought back. My mother not only hit but beat my father who was a policeman. What they were doing was dangerous and could’ve cost them their lives.