Some years ago, if you sent Brian Lara an e-mail, chances were he’d respond personally. It is a sign of how things have evolved that now his correspondence is managed by his recently hired English communications manager, who confessed that she knows little about cricket – and it is striking that such knowledge was not a job requirement.

It suggests that following his retirement from international cricket in 2007, Lara is constructing a life that may reside in the house that cricket built, but is certainly spreading out to encompass more diverse activities.

One of them is his role as a fete promoter, a domain where he can operate within something of a comfort zone, given his love for partying, and his awareness of the premium value of celebrity. Right through the 16 years of his international cricket career, everyone wanted a piece of Brian Charles Lara. An autograph, a smile, a touch, a howdy, maybe even a handshake, anything from the superstar was worth the jostle.

Famously aloof, but remarkably entrepreneurial, Lara realised he could kill many birds with one stone by hosting massively hyped Carnival parties at his Chancellor Hill mansion in Trinidad. He is the type locals would call a Carnival baby, and he knew that people would pay handsomely to say they had been to his house and partied up close to him.

Those events were such a success that he soon extended his Carnival spirit to the mid-year Crop Over in Barbados, where he hosts similar ones at his Ebworth Plantation in St Peter. His annual fetes have become calendar musts for the socially mobile, and take a sizeable chunk of his time. That’s part of the post-cricket image that Lara has invested in heavily as he seeks to reposition himself and to ensure that he loses none of the opportunities offered by his fame as a batsman.

About five years ago, together with friends, he set up the Lay Management Group to organise such events, intending it to fund not just the Pearl and Bunty Lara Foundation (in memory of his deceased parents), but to help young athletes as well. Party management entered his portfolio readily – he’d been doing it for years while still active in cricket – but it has grown, as has the range of his activities.

At 40, Lara is much more than a retired cricketer. He still endorses products like bmobile telecommunications and Angostura’s LLB in Trinidad and Tobago, but he has found ways to weave his cricket celebrity into affiliations that project him as a role model for youth. He is an adviser to the University of Trinidad and Tobago, where he graces many of their sporting programmes with his presence and inspirational words to students. It is within this framework that he fulfils most of his sponsorship deals: attending events, addressing young athletes, cutting ribbons, patronising charities, and making occasional appearances on a cricket field.

It sounds very statesmanlike. Certainly, Lara is aware that, having bestowed on him its highest honour, the Trinity Cross (as it was then known), his country expected him to carry himself in an ambassadorial and diplomatic manner henceforth. The same was expected regionally after he was honoured with the Order of the Caribbean Community.

As he marked his 40th year on May 2, Brian Charles Lara, TC, OCC – for whom a promenade was named in Port of Spain, as well as a massive sports complex (admittedly five years in the making and still incomplete), in whose honour a series of special stamps were issued to mark his Test record of 400, whose name is associated with a cancer foundation in Trinidad, whose career was celebrated in 2007 with an exhibition at Lord’s Museum – knows that this life after cricket owes everything to the cricket he made and gave to the world.

His journey was a deep and complex one, fraught with extremes of adventure and misadventure, and deeply textured by magisterial performances shadowed by inexplicable behaviour, so that even now, when he no longer participates in its hurly-burly, his story is still a fascinating one, and his absence has affected the game’s future in the West Indies as profoundly as his presence did when he was “the Prince of Port of Spain”.

A brief look at his career illustrates some of its complexity.

Halfway towards his 22nd birthday – in November 1990 in Karachi – he slipped into his dream team. It must have been a turbulent entry. He’d been captain of Trinidad and Tobago’s national team for a couple of years. His talent had already been heralded, but he had remained at the periphery of West Indies captain Viv Richards’ victory-loving team, which had only lost eight of 50 Tests.

He finally made his Test debut in the third match in Lahore, and though he put his head down and scored a patient 44 off 89, he was upstaged by the man of the match, Carl Hooper, with 134. He wasn’t in the team captained by Richards that next toured England for five Tests from May 1991, but after that Lara became a constant on the West Indies team.

But he had entered a team that, though still high, was no longer ascending. Indeed, history records that it was just slipping off its plateau and was beginning a long descent.

The team hit bottom in May 1995, during the fourth and final Test against Australia at Sabina Park. Symbolic of the twist in the tale were the scores: the Waugh brothers, Steve and Mark, made 200 and 126 respectively; Lara was out for a duck. It was the end of an era.

It is against this background that many of his accomplishments stand out. Lara drew international adoration after his extraordinary performance in 1993 at the Sydney Cricket Grounds in Australia (source of his daughter Sydney’s name) when he scored 277 runs of such majestic pedigree that commentator Tony Cozier immediately dubbed him the new prince of cricket. The following year, on April 18, he finished the job he’d started 538 balls before, and broke the world record for highest Test innings with 375 at the Antigua Recreation Ground. That innings was packed with 45 boundaries, and the spotlight now focused on him permanently.

Shortly after, he took off for England to pick up his new £40,000 contract with Warwickshire. In his debut on April 29, 11 days after the Antiguan spectacle, Lara scored 147 against Glamorgan. By May 23, he had collected five first-class centuries in a row, and another world record for consecutive first-class centuries was in sight. He missed it when he was out for 26 at Lord’s, but in the second innings he recovered enough to make 140 off 147 balls. The next month, he broke the first-class individual record with 501 runs at Edgbaston. He had become the first player to score seven centuries in eight first-class innings.

No cricket lover would ever want to miss a Lara innings again: the possibilities were too rich. He’d shown he had the moves, and now he was showing a phenomenal appetite for runs, bringing a level of discipline and concentration not normally associated with the flamboyant stroke-makers of West Indies cricket lore.

His record suggests a mind that conceives in epic proportions. Of his 34 Test centuries, nine were over 200 (including his first, 277, and his 375 and 400 not out); 19, which is more than half, were over 150; and only nine were under 130. None of the other leading Test centurions come even near to his massive accumulation of 5,889 runs off his centuries alone. His final Test tally was 11,953 runs; just under half of them came from his centuries. Of his 34 centuries, nine crossed 200, and 19 were over 150. It is a phenomenal set of figures.

Lara’s ability to concentrate and the stamina and discipline to keep going could not have come with a cavalier approach to his cricket. Rather, they speak of something ingrained in the child who would set up potted plants as fielders so he could aim for the gaps, and who would practise his strokes long after other boys had lost interest.

Although he was making all these runs – ten years after the 375 world record, he reclaimed it with 400 not out, after Australia’s Matthew Hayden had held it for only a few months – Lara’s team was still a losing team on the Test table. Each personal victory must have been bittersweet.

His role on the team shifted more than any other player in West Indies history. He went from star batsman to holding the captaincy three times – a sign of the transience and volatility of the team itself.

Captaincy, after Viv Richards, had been a series of short terms: Richie Richardson, Courtney Walsh, Brian Lara, Jimmy Adams, Carl Hooper, Brian Lara, Shivnarine Chanderpaul, then Lara again. So many players passed through the team that more were capped in that period than in the first 50 years of West Indies Test cricket.

One criticism of the team in that decade was that players did not have a disciplined approach to preparation for games. They were thought to shirk training sessions, ignore nutritional guidelines, and to have a casual approach to physical fitness. The team went through an appalling slide to the lower end of the rankings, and Lara, as captain, faced much of the criticism for poor performances. The pressure on him had always been great, even when he was not captain – in 1995 he had famously declared that cricket was ruining his life – but as captain he bore the brunt of accusations that he promoted divisiveness among the team, that he was only interested in money, that he was selfish and could not see past his own interests.

Whether or not there was truth in these statements, post-Lara, the nature of the problems besetting West Indies cricket remain so unchanged that he could scarcely have been the source.

His presence did generate some change, and his shrewdness in money matters created an awareness of financial values that was never quite so pronounced in the regional game. Like his methods or not, it was primarily through Brian Lara that West Indies cricket lifted its ante and became a sport with money for players. What Kerry Packer pioneered in the late 1970s with his World Series Cricket, which revolutionised income levels, was taken to maturity by Lara’s success and his close attention to maximising revenue. No other player in West Indies cricket history has benefited as handsomely from sponsorships and endorsements as Lara. The West Indies Players’ Association (WIPA) was fortified by it and the West Indies Cricket Board was forced to accept that it now had to negotiate with players. It created a whole new dynamic in the relationship between players and the WICB, but more specifically, Lara, as both a player and as captain, was a powerful force, who could not be ignored.

As his player days drew to a close, his relationship with the WICB became more openly confrontational. In an interview with Cricinfo magazine, he’d said the West Indies cricket problem was not simply a player problem, but “can stem from deep-rooted problems in the administration. I don’t think you’d see an indisciplined team if you have a disciplined board. If you have a disciplined board, they would know exactly what they want from their players. You need to see the whole spiral, where it starts from.”

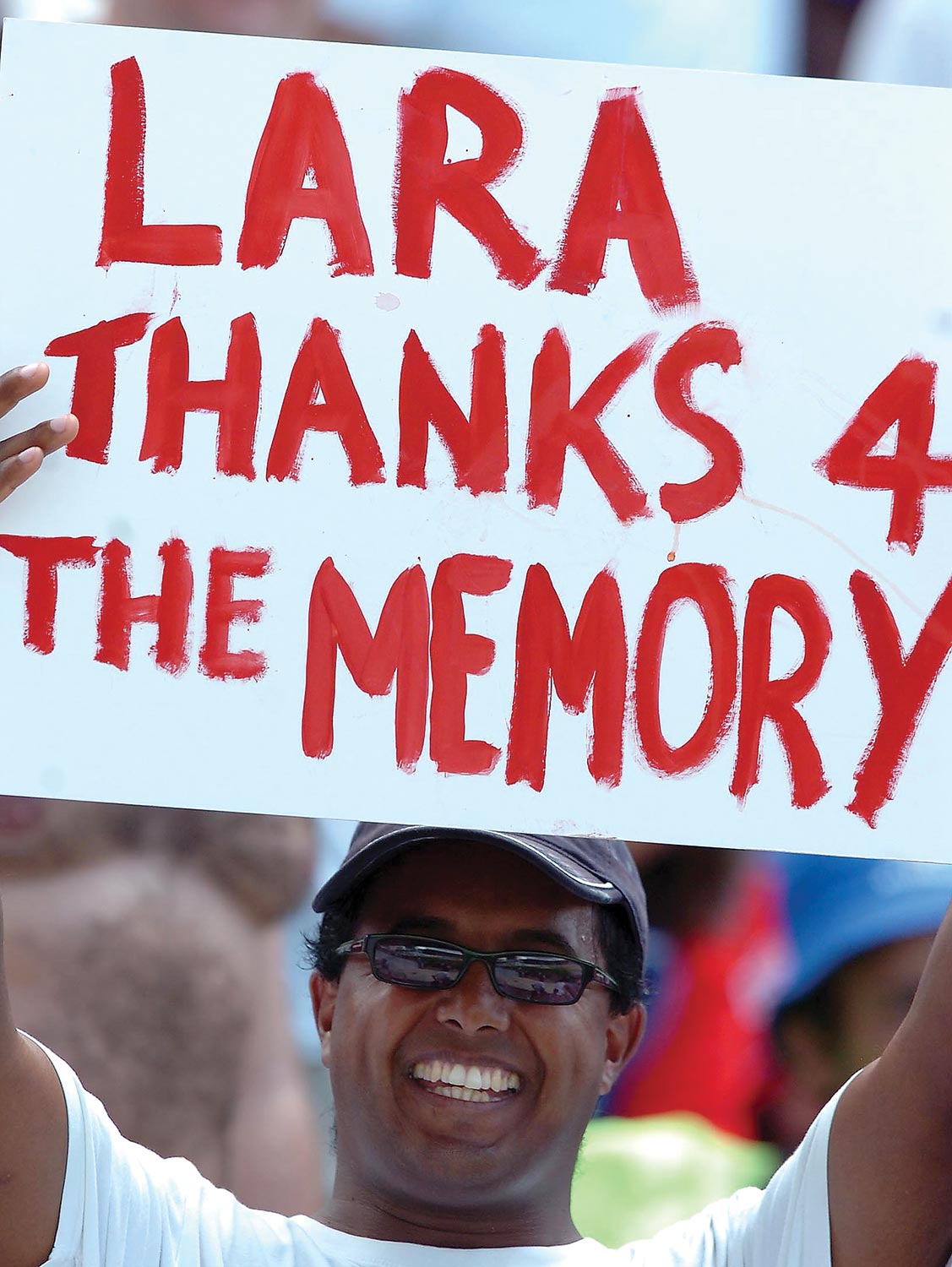

This did not win him friends within the administration. So by the end of the 2007 World Cup series, hosted by the West Indies, it came as no great surprise when he announced his retirement.

“My life has been played out in public,” he said in a poignant farewell address that many absorbed as the closure of a remarkable era of world cricket. Those who’d followed his resolute career and watched him feed his enormous appetites understood that his love of the limelight would ensure that he was just turning to wheel and come again.