“Turn her out!” “Turn her in!”

The traditional orders for stopping and starting the Caribbean’s only operational sail-powered sugar mill echo once again across Antigua’s Betty’s Hope Estate between the months of February and June. The Estate, one of the island’s most prosperous sugar plantations for about 300 years, is now preserved as a heritage site and open-air museum.

During a fair to mark the occasion in mid-June this year, the sails of the mill will be taken down for the duration of the hurricane season, just as they were for almost three centuries. They will be put back up in February, as they were every year at the beginning of the sugar cane harvest.

It is sugar, with its by-products molasses and rum, that is at the core of West Indian history. Sugar created the African slave trade, the countless regional European wars, hundreds of incredible fortunes and centuries of abject misery. Except in a few islands like Barbados and Trinidad, sugar is no longer king; indeed on some islands it is no longer grown at all. Faced with declining prices and stiff competition from the European sugar-beet industry and the establishment of huge sugar cane plantations in the southern United States, the Caribbean sugar industry went into decline in the late 1800s and was never to recover. The last cane to be ground at Betty’s Hope was in the mid-1920s, and by the 1940s the estate’s gradual decline had become terminal.

But when sugar was king, Antigua was one of its castles. And Betty’s Hope was its premier knight. British colonists from nearby St. Kitts settled Antigua around 1632.

As was the custom in those unenlightened days, the forests and undergrowth of the island were cleared to make way for cash crops — cotton, spices, tobacco and sugar were among the chief commodities. A few decades later, sugar pushed all the other crops into the background and emerged as the dominating industry, where it remained for nearly 300 years.

Leeward Islands Governor Christopher Keynell established Betty’s Hope Estate, named after one its founder’s daughters, around 1652. He died in 1663 and left the estate to his widow, Joan. In 1666, the French seized the island and with it Joan’s 60 slaves and her estate. For unknown reasons, they torched the buildings and the plantation and either slaughtered the slaves or spirited them away, probably to even worse fates on a French-owned island. Joan Keynell fled to Nevis.

When the invaders left in 1667, Joan returned from her exile to find a plantation in ruins, deserted and in fact not even hers anymore. The British Parliament had annulled all land claims in existence before the French incursion, and in 1674 Betty’s Hope went to Colonel Christopher Codrington of Barbados — whose family name is one of the most prominent in the history of the British West Indies.

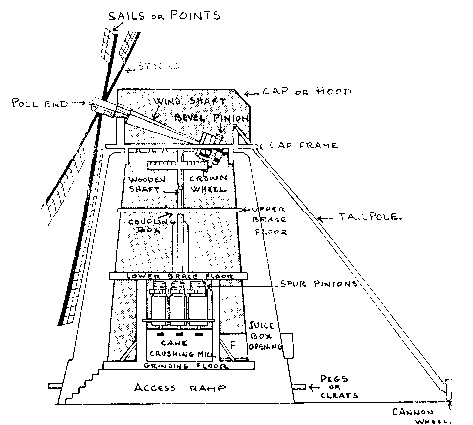

The colonel moved to Antigua that same year and resurrected the estate, which until 1944 remained in the hands of the Codrington family, long since repatriated to England (in about 1710). Betty’s Hope sugar mill was built by the Codringtons — or more accurately their “attorneys,” who oversaw the business — in about 1700 or shortly thereafter. Now Betty’s Hope has been revived from the grave yet again, this time not for the profit, to be sure, but for the enjoyment of tourists and locals and as a living piece of Antiguan history.

Betty’s Hope Trust, which is responsible for the ongoing restoration work, won the prestigious Islands magazine Ecotourism Award in 1996. Michele Henry, executive director of Antigua’s Historical Society, which operates the Museum of Antigua & Barbuda, said the restoration of Betty’s Hope is being undertaken in stages. The first phase, the creation of the Interpretation Centre, was completed in 1991. The second part — to get the 17th-century mill back in working condition — began in 1993, with crushed cane being produced again beginning in June 1998. Henry credited Antiguan historian and archaeologist Reg Murphy and American millwright Jerry Bardoe for their dedication to the project.

The third phase of the project will be to build a replica of the slave village, which will feature three different styles of ethnic architecture. June’s final turn of the sails will feature an educational fair with specially bottled souvenir Betty’s Hope rum on sale.

Access to Betty’s Hope is via a short dirt road on the south side of the main road to Willikies and Long Bay. Look for the low-key signpost on your right as you head east. The visitors’ centre is open Tuesday to Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Phone 268-462-1469 or the Museum of Antigua and Barbuda at 268-462-4930 for more information. Contributions to the restoration project can be sent to Betty’s Hope Trust, P.O. Box 103, St John’s, Antigua, West Indies.