On the surface, Frederick “Toots” Hibbert and Robert Nesta Marley have only a few things in common — mainly that they’re both Jamaican and both internationally recognised and acclaimed icons of reggae music.

And that, I thought, was about as far as it went. Their styles of reggae could hardly be more different — Toots’s fervent, gospel-infused, gravel-voiced, Bob’s rootsy and message-driven, with a raspy tenor that’s more sinewy and penetrating than supercharged.

So no one could have been more surprised than me when I delved a little more closely into Toots’s history the other day for a newspaper story I’d been asked to write about him. Like most reggae enthusiasts, I was familiar with the nuts and bolts of Toots’s career — but my jaw dropped when I realised how closely it paralleled Marley’s.

Consider:

They were born in the same year, 1945, in rural Jamaica, Toots in the small town of May Pen, Marley in the hamlet of Nine Mile. Both moved to the island’s teeming capital, Kingston, and found themselves as teenagers living in Trench Town just as a new and uniquely Jamaican style of music called ska was in its infancy. Both had their sights on a career in music, and both were influenced by American soul artists like Otis Redding, Ray Charles, Brook Benton, Jackie Wilson, the Drifters, Sam Cooke and Wilson Pickett. Despite being from devout Christian church-going families, both quickly embraced the then widely scorned Rastafarian movement. And that’s where it starts to get really spooky.

Toots made his first recording — a ska belter called Hallelujah — in 1962.

Marley made his first recording — a ska belter called Judge Not — in 1962.Marley released his first significant hit — as lead singer of the Wailers — in 1964, a song called Simmer Down, recorded in Studio One, the most prolific and influential music factory in the Caribbean, on which the young vocal group was backed by Jamaica’s leading session musicians of the era.Toots released his first album — as lead singer of the Maytals — in 1964, an album called I’ll Never Grow Old recorded in Studio One.

And both had so much trouble getting even modestly compensated for their chart-topping efforts by Studio One czar Clement “Coxson’” Dodd, whose genius as a producer and sound system pioneer was often overshadowed by his notorious reluctance to pay his hit-making musicians, that they were soon to part company with Dodd. Before long both were working with Leslie Kong, the producer who was also responsible for Desmond Dekker’s It Mek, one of the first songs to introduce Jamaican music to the outside world, and for whom Toots recorded a 1968 hit single called Do the Reggay — the song that’s widely credited with introducing the word reggae, albeit with a slightly different spelling.

After a frustrating period in the late Sixties — during which Toots spent a year in prison on marijuana possession charges he swears to this day were set up by a jealous rival singer, and Marley, fed up with the machinations of the Jamaican music industry, spent two lengthy periods in the United States — both were signed by Chris Blackwell’s small but influential Island Records.

The Wailers’ first Island recording, 1973’s Catch a Fire, is widely credited with being one of the two albums that introduced reggae music to millions around the world. The other is Island’s soundtrack of the 1972 made-in-Jamaica cult-hit film The Harder They Come, which features two Toots tracks, Sweet and Dandy and Pressure Drop.

That’s when their career paths started to drift in different directions. Marley went on to global superstardom, the cover of Rolling Stone and a succession of critically acclaimed and commercially successful albums and SRO live performances on every continent before succumbing to cancer at 36 in 1981. Twenty-six years after his death, he’s still known universally as the King of Reggae.

Toots was never to make it quite that big. But he lived to steal the show at the celebrations for what would have been Marley’s 50th birthday at 56 Hope Road in Kingston, where he turned Bob’s Talking Blues inside out and upside down. For something like 20 minutes, Toots made the Marley number his own.

I’ve seen Toots perform more times than I can remember, mainly in Canada and Jamaica, and this was the single most riveting of all the hundreds of numbers I’ve heard from him. “My style is different from his,” he says of his late friend Marley. “But he is my favourite singer from Jamaica.” It showed, loud and clear, on that memorable February evening in 1995.

Today, at 62, Toots continues to be revered not only by reggae fans around the world, but by a smorgasbord of fellow musicians who love nothing more than to tour and record with him.

He won a reggae Grammy, his first, for his 2004 album True Love. He’s still touring constantly, and in recent months has shared billing with the Rolling Stones in Finland, Sweden and Denmark, and with Jimmy Buffett and the Dave Matthews Band in the US.

Toots has also been around long enough, and successfully enough, to forgive, if not quite forget. His new album, Light Your Light, contains a tribute to the same producers — and particularly Coxsone Dodd — who used to short-change him and his young contemporaries so blatantly all those years ago.

“The old-time producers are good people,” says Toots, “and I always talk good about them….Even if I say they don’t pay me.”

Toots doesn’t talk quite so good about the dancehall music that’s dominating Jamaica today. In fact, he’s quite dismissive: “All these youth today, they have to listen to Bob Marley, my songs, Jimmy Cliff. They have to listen to us to learn something.”

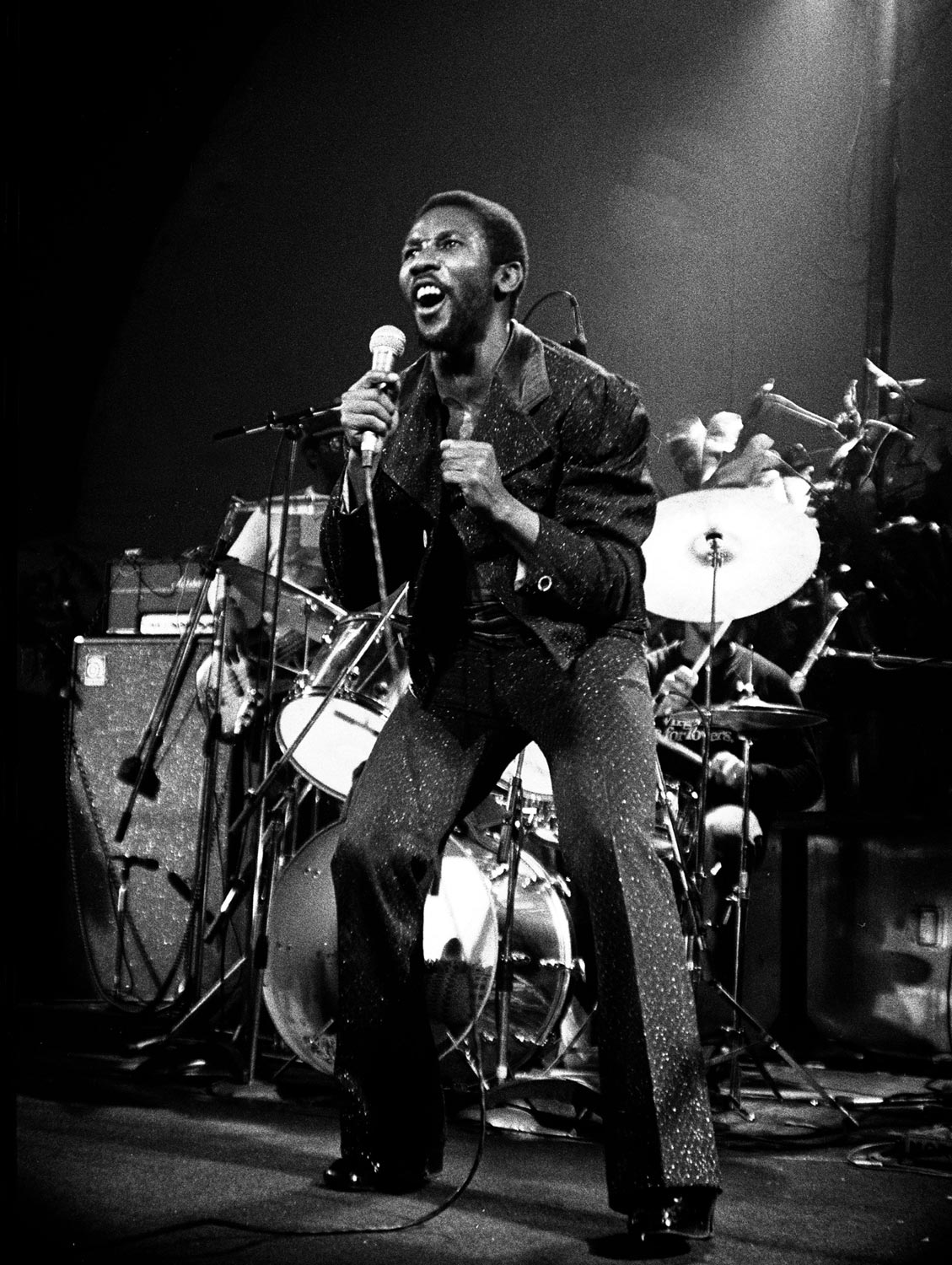

What about his stage show? I first saw him perform live in Montreal almost 30 years ago. It’s a show I remember well, largely because I was one of the promoters and managed to lose a bundle of money despite selling out the hall (counterfeit tickets, if you’re wondering…hundreds of them). Most recently, I caught him at Chicago’s House of Blues.

The difference in the two performances? Well, I have to say Toots looks older these days than he did three decades back. About three years older. And, after spending most of his adult life touring virtually non-stop he’s as fresh and enthusiastic as he’s ever been, a master of the stage, a vocal powerhouse and an extraordinary showman. Long may he continue.