It started out from a little restaurant at Lawes Street and Ladd Lane, “Nanny’s Corner”, in Kingston in the ’50s: we used to play music in the place on a Morphy Richards radio, play Billy Eckstein, Sarah Vaughan, Lionel Hampton, Louis Jordain.

I was a cabinet-maker, and I did a course in automobile mechanics, used to train at the Ford Garage on Church Street, and I attended a lot of orchestra dances in the early days. But then the rhythm and blues came in about ’53, and the highlight of the sound system was after I came in it.

I used to attend dances when Duke Reid was playing, and play some of my sides, and his fans always look forward to seeing me coming with my little case of records, so I eventually went into the sound thing myself. Duke was a close friend of the family, and the rivalry was clean: I respected Duke because he was my senior by a couple years, but I was more musically knowledgeable. With importation, I had the stronger set of records, and when we started recording locally, I had the stronger set of records; but Duke was so strong financially that, even if I had a contracted artist, Duke would still insist and use them, and that kept me on the ball, trying to produce better stuff. Duke was in it because it was a business, but music is really the love of my life; Duke had to depend on somebody to tell him, “This is a good tune,” whereas the first couple bars that you sing, I could identify whether this would be a hit, and I thank God for that blessing.

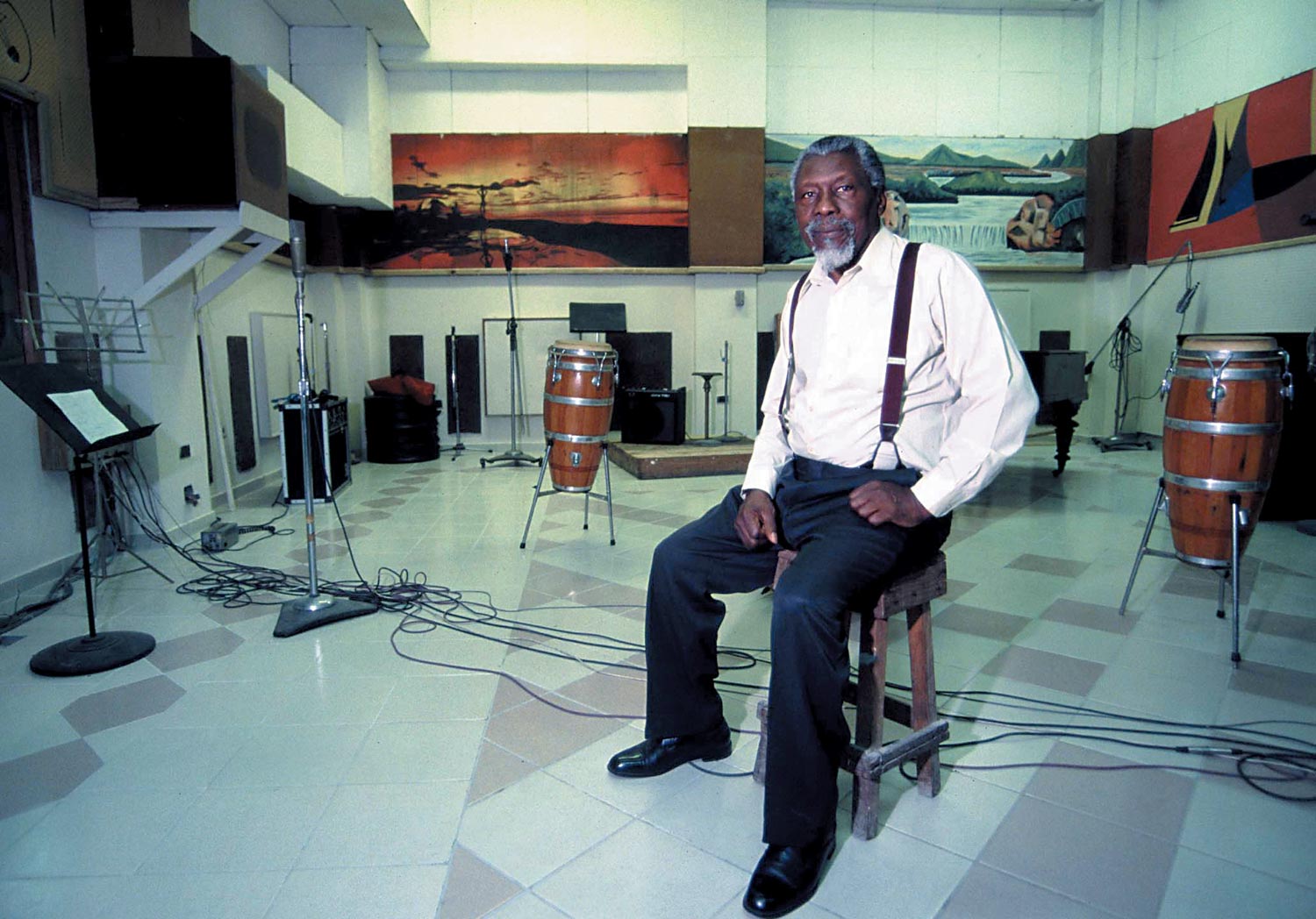

As a matter of fact, I am the person who discovered the musicians, then the other producers would use the same musicians that I use. From 1961, Jackie Mittoo, Roland Alphonso, Jah Jerry, and Don Drummond was contracted to Studio One, and Tommy McCook, Lloyd Knibb, Lloyd Brevett, and Johnny Moore played weekly sessions; after the ska became dominant and these musicians was the major recording backing band, I decided to form the band the Skatalites. I really had the edge, because of all the other sound system men, I was really in the studio more often, and had a lot of releases that hit, so anybody looking for a producer, most would head to me. Ken Boothe and Stranger Cole did a couple of tracks, and after hearing Ken’s voice in Artibella and World’s Fair, I encouraged him to go solo.

With Bob Marley and the Wailers, [percussionist] Seeco Patterson brought them here, and I was amazed; it knocked me out because I admired the harmony that they had. They came as the Juveniles, and two girls was in the group; they had that team sound, so I was crazy about them, because we had nothing like that before in Jamaica — that was coming like a Frankie Lymon kind of thing.

Junior Braithwaite was the lead singer then, but he had to join his parents in Chicago, then I selected Bob as the leader; looking back, and seeing that he’s such a big star, I feel good to know that I’d seen that in him at a very early stage. When Burning Spear came here in 1969 the group was a duo; the styling again hit me as something new and different, but the guy singing with Winston Rodney wasn’t saying nothing, so I had to take him to one side and say, “I’m willing to invest in you, but the other guy . . . don’t worry about harmony, because we always have house harmony in the studio.” There again, I am really happy to know that I can pick a winner.

We had already recorded Rastafari music, because I was the first person ever to use Count Ossie on a recording session with Rockaman Soul and Another Moses. At that time Prince Buster was working for me, then Buster came long after and used them for Oh Carolina. I also used to invite them to dances that we had, away from the sound system: we would have them coming on and chanting, so we knew the Rasta thing was popular and would make sense to invest into.

I believe in God, so I founded the Tabernacle label to record church music; I was happy being part of getting the message around, and even the part of recording spirituals on Sundays, I said that I was doing God’s work. The more current work at Studio One, we did albums like Brother to Brother with Glen Washington, which is a top seller, and we have a release with an American singer by the name of J.D. Smooth, and also an LP labelled Reggae A Go Jazz, with American tenor sax player Cliff Jordan and trumpeter Roy Burrows. I will produce some dancehall stuff, but some of the deejay material of dancehall, I don’t know what to do with it.

I’m more from the old standard: I love a full band sound with horns and arrangements, so to just have the drum going there — that tin-pan thing — and the bass not playing something melodious, I can’t stand it. You have quite a few deejays today, but don’t bring them, ’cause I don’t know what to do with them — I wouldn’t even try, I just stick to the old format.

As I see it, God is what I depend on; the Lord holds the future for me, but in the meantime, I will keep on recording and producing vintage artists and new artists. I’m just working on the feel, hoping to please the world with music as usual, and I’m thankful for that.