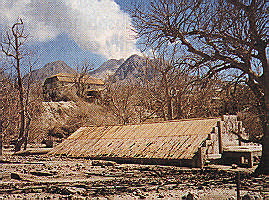

It was difficult to grasp the fact that it was possible to walk across the verandah and through the shutters straight into a first-floor sitting room with its elegant chaise-longue, television and other comfortable items of late 20th century life: apart from a thick covering of ash, the room was undamaged. Outside, the scene was of the aftermath of war and the stillness of sadness.

This was in Plymouth, the once agreeable capital of Montserrat, where ash now literally fills the streets up to the arm-pits of buildings, months after the Soufrière Hills volcano sent its pyroclastic flows to burn out the heart of the town. The sitting-room into which we had walked belongs to the family of a Montserratian lawyer. It was his first sight of the devastation of Plymouth. He had known from photographs that it was incredible; now he was seeing it for himself and it was just that.

For strangers, the short journey — with a police convoy — from the safety of northern Montserrat to Plymouth, from green to grey, from the normality (even under crisis conditions) of Caribbean street life into emptiness and lifelessness, is both touching and macabre. It is hard to imagine the range of sensations experienced by Montserratians.

Before walking into the desolation of what had once been George Street, we had parked the truck on the bay front, close to the British red telephone box now three-quarter buried. Then a sharp bird’s cry came from one of the almost leafless coconut trees: a beady-eyed thrasher darted away. Or perhaps it was a phoenix. For there is talk that the grass is already pushing up through the burned acres of eastern Montserrat while, all over, the tough old oleanders are flowering pink among the ash. The old clichés about renewal are not only true but necessary.

After nearly three years of displacement and loss (two-thirds of the population of 11,000 or so have left since the volcano first began to stir in July 1995), and with only one-third of the island habitable, the development of the north now becomes a priority. By April, there had been no “ashing” for some time and the volcano was “quieter” than it had been for months. Could it be the beginning of the end? It was too early to say, but fingers were crossed.

Homes are the greatest need, and the lack of them is what has forced so many Montserratians to leave. In April, 512 souls were still living in shelters: schools and churches hastily turned into what were meant to be temporary homes. But there was nowhere else for people to go and, for those who didn’t “relocate” to the UK or to other Caribbean islands, shelter life was often the only alternative. It was not much of a choice, as the trenchant Chief Minister David Brandt has pointed out on many occasions.

“We’re only here because we couldn’t do any better,” said a dignified elderly lady on the porch of St Peter’s Anglican Church, where clothes were hung out to dry in the churchyard. There were bunk beds, plastic bags and, for the lucky ones, screens to divide them from other families and crying children. They sit on their beds, eat there, children do their homework there. Some may have a precious possession, rescued from their home, others have nothing. So many had to leave taking only their clothes and documents (a British passport, with its limit codicil, “Colony of Montserrat”).

Slowly, too slowly, the British-financed new accommodation is going up: box-like pre-fabs at Davey Hill were completed in January; the 50 (nicer) homes at Look Out were still not finished in April. And Montserrat awaits Caricom’s contribution: more pre-fabs to be put up by the Jamaica Defence Force. Another need is for access to cheap mortgages (promised by the British last year, but the islanders are still waiting), opportunities to buy land and start-up money for small businesses (another promise).

Even so, trucks loaded with cement and timber line up outside builders’ yards, roads are being re-tarmac’d, and Little Bay, once a sleepy hollow, has become the island’s only point of entry (apart from the helicopter pad). It may be a mass of containers and makeshift buildings at the moment, but Little Bay is pinpointed as the site of a new town, a new capital.

The charm of this delightful (if shrunken) island cannot be repressed. There is an open, breezy feel to the north, in the ghauts (the dry ravines) that divide ridge from ridge, where breadfruit and mango rustle hopefully. There are no hotels yet (all were in the south), but there is some bed and breakfast accommodation. Visitors are welcome: to see a living volcano, to visit the Volcano Montserrat Observatory or just for the curiosity of going to a bank relocated in a former bar or to a government office squatting in the former kitchen of a smart villa.

Montserratians who once lived in Plymouth and the south are now beginning to discover the north of their island, which was always poorer and less fertile. They are exploring trails — up the Bunkum River, for example, with its great overhead cliffs clad in tree ferns and lianas; or the hard hike up Katy Hill; or to the wild valleys and oceanic views beyond the Silver Hills. Whatever has happened, said a taxi-driver, “we love this little island of ours.”

Those who remain are determined to stay. They want to be in Montserrat. All have tales of great loss, shoved this way and that by the volcano (and by politics). All are looking to face the challenges of a new Montserrat. As a senior civil servant, with her own stories of dislocation and separation, said from her overcrowded office: “Well, whatever it’s been, it’s never been boring.”