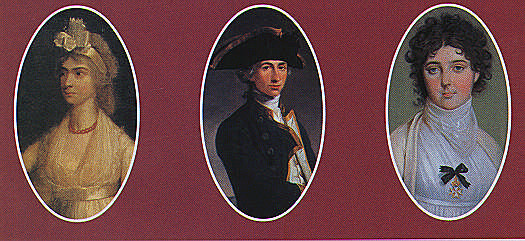

All the world loves a lover. The love between Lord Horatio Nelson and Lady Emma Hamilton has passed into the realm of mythology. But what of Fanny Nisbet, Nelson’s wife of 18 years, of whom he said: “I find my domestic happiness perfect. I am possessed of everything that is valuable in a wife”?

It is true that the final disintegration of the marriage was due to Nelson’s affair with Emma. In 1801, when after 14 years of marriage Fanny and Horatio were living apart, Fanny heard that Emma had given birth to the child she had always hoped for with Nelson, and wrote to him: “Do my dear husband, let us live together, I assure you again I have but one wish in the world: to please you. Let everything be buried in oblivion, it will pass away like a dream.” The letter was returned to her with the words “opened by mistake by Lord Nelson but not read”.

Fanny could simply have accepted his relationship with Emma, thus remaining in contact with the man she loved. This was a common choice in the 18th century, when divorce could only be obtained by an Act of Parliament; there were many convenient ménages à trois, including that of Lady Emma Hamilton, Sir William Hamilton and Lord Nelson. It was commonplace for a naval officer, away at sea for years at a time, to be unfaithful to his wife.

But perhaps she could not bear her husband’s flaunting of his mistress. William Haslewood, Nelson’s solicitor, recorded a scene at the Nelson household, which in effect began the separation. They were all seated at the breakfast table, where Nelson was recounting a story which included mention of Emma Hamilton. Fanny, greatly agitated, jumped to her feet and declared: “I am sick of hearing of dear Lady Hamilton and am resolved that you should give up either her or me”, to which Nelson replied: “Take care, Fanny, what you say, I love you sincerely but I cannot forget my obligations to Lady Hamilton or speak of her otherwise than with affection and admiration.” Fanny left the house; shortly afterwards Nelson went to stay with Sir William and Lady Hamilton at 23 Piccadilly.

The Admiralty made him a Rear Admiral of the Blue and gave him the command of the Channel Fleet. Before he left to take up his new post, he visited Fanny at the house she had rented for them in Dover Street. She had taken to her bed, and when Nelson entered the room she held out her hand to him, which he took. She then said: “There is not a man in the world who has more honour than you. Now tell me, upon your honour, whether you have ever suspected or heard from anyone anything that renders my own fidelity disputable.” “No,” Nelson replied. These were the last words they ever said to each other.

Fanny lost the battle for Nelson’s heart, but, to Emma Hamilton’s chagrin, she stood her ground in society. She still attended the Levees given at St James’s Palace by King George III and Queen Charlotte, and often went to Court. She remained a favourite with many of Nelson’s naval friends. Eventually, she was ostracised by Nelson’s family, with the exception of his father, the Reverend Edmund Nelson. The settlement of £1,800 a year which Nelson gave her must have gone some way to ease the sting of his betrayal, but it must have taken a great deal of courage on Fanny’s part to stand tall, as she did, in the face of all the gossip.

The real key to Fanny’s strength lies in her upbringing and character. Born in Nevis in the West Indies in 1761, she was just two years old when her mother Mary Woolward died giving birth to a son, William. In the Caribbean, the custom among the governors and sugar plantation owners was to send their sons to school in England, so Fanny grew up to be her father’s constant companion and the apple of his eye. He was the Senior Judge in Nevis and the partner in an export business.

The West Indies was, at this time, under English rule, and trade was brisk and profitable. Fanny received a good education under the careful eye of an English governess and soon became accomplished in French (the court language), painting, drawing, playing the harpsichord, singing and dancing. In short, she achieved everything to make her desirable and attractive company, and was soon very much sought after by the eligible bachelors on the island. Being a dutiful daughter she promised her father never to marry anyone of whom he disapproved.

Among the beaux who courted her, she favoured a successful young trader, Daniel Ross (her father’s favourite), and Dr Josiah Nisbet. It was Dr Nisbet who attended her father when he suffered a fatal attack of lockjaw in January 1779. Perhaps this community of grief brought the two together. Whatever the reasons, Fanny fell in love with the eccentric Josiah, who had obtained his doctorate in rheumatism at Edinburgh University before returning to his home in Charlestown, Nevis. He was often to be seen prowling around the island looking for plants and shrubs with which he made medicinal compounds.

Their marriage in June 1779 was a big society event; Fanny was given away by her adoring uncle, the President of Nevis, John Herbert, at whose grand house, Montpelier, the couple held their wedding breakfast. They were radiantly happy together for the first six months of their married life.

But then Josiah became ill. His symptoms included fever and delusions, but no one could find a cause or a cure for his ailment. It was decided that Josiah should return to England, where the cooler climate might be beneficial to him. The Nisbets set sail for Southampton and, on arrival in England, settled in Salisbury, near the home of Josiah’s uncle, George Webbe. In May of that year, 1780, their son, also named Josiah, was born.

His poor father failed to make a recovery and died in October of the following year. So within the space of two years Fanny had buried a father, married, given birth to a son and buried a husband. As soon as her uncle, John Herbert, heard of Josiah’s death, he asked Fanny to come back to Nevis to live at Montpelier and supervise his household. So, Fanny, now 22, returned to Nevis as a mother and a widow.

Three years later, Captain Horatio Nelson arrived in the Leeward Islands as a senior officer of His Majesty’s Navy. He had already gained a reputation as a bold, dutiful and patriotic officer. He was second-in-command to Richard Hughes, but found him lacking in discipline. He complained that Sir Richard, who lived in Barbados, spent more time practising on his violin than he did attending to his squadron.

It soon came to Nelson’s notice that Sir Richard had been badgered by the West Indian traders into turning a blind eye to the Navigation Acts, thus allowing them to trade with American ships. Even before the American War of Independence, these Acts, designed to protect English shipping, were almost impossible to enforce. However, Nelson with his fierce sense of duty could not let this pass. He mounted protest after protest, first to Sir Richard Hughes and then to the Admiralty in England.

Eventually he seized four American merchant ships which had refused to depart from Nevis waters. The islanders were furious at this threat to their livelihood, so they collected money to enable the owners of the American ships to sue Nelson for assault and wrongful arrest. Nelson was forced to stay on board his ship, the Boreas, for two months in order to avoid being arrested and thrown into prison. The cost of his defence was met by the Treasury, and Nelson’s seizure of the American ships was upheld in court.

He may have won his case, but he now found that he was persona non grata at nearly all the merchants’ houses in Nevis — all, that is, except Montpelier, for John Herbert admired the way the sprightly Captain Nelson had remained true to his principles. Nelson’s early morning arrival at Montpelier gave the householder a surprise. “Good God!” he reported. “If I did not find that great little man of whom everyone is so afraid playing in the next room, under the table, with Mrs Nisbet’s child!”

Nelson was soon to declare himself in love with Mrs Fanny Nisbet, and she was soon won over by his disarming honesty and his code of honour and duty. He was persistent and very persuasive. “My whole life shall ever be devoted to make you completely happy,” he declared, though adding “whatever whims may sometimes take me. We are none of us perfect.” Fanny was relieved to have found a surrogate father for Josiah. Nelson always spoke of Josiah in his letters to her. “How is my little Josiah?” he would ask.

John Herbert gave his consent to the marriage, providing the couple waited until he had handed over his house and estate to managers, who would run his affairs in Nevis while he spent his retirement at his mansion in Cadogan Square, London. The marriage took place at Montpelier on March 11, 1787, with Prince William (the future King William IV), who was under Nelson’s command at the time, standing in for Fanny’s father.

Although Horatio wanted Fanny to sail back to England with him on the frigate Boreas, she decided to accompany her uncle on a merchant vessel. This caused a few raised eyebrows among Nelson’s crew, especially in view of the fact that on the voyage back, Nelson became so ill that at one point he was not expected to survive the journey.

Fanny and Horatio went to live with his father Edmund at the vicarage of Burnham Thorpe in Norfolk. Fanny found her health suffered in the cold East Anglian climate, but she was sustained by her love for Horatio, his father and young Josiah.

In 1793, after war was declared with France, Nelson was recalled for service, and this time he took with him his 13-year-old stepson. Fanny was very distressed at the idea of losing both her husband and her son to the sea, when they had all been together on land for five years. Her distress led her to make mistakes in packing Nelson’s belongings, which annoyed him — “You forget to send my things,” he wrote to her.

Within the year, Nelson had won a reputation for fearlessness. In the famous battle of Cape St Vincent he boarded the enemy’s San Nicolas crying “Westminster Abbey or glorious victory”. Back in England, Fanny read the news with trepidation, and wrote to Nelson: “You have done desperate actions enough, you have been most wonderfully protected, may I — indeed I beg that you never board again.” Concern for her husband’s safety was making her ill, she said. This did not please Nelson, who wrote to her: “Why should you alarm yourself? I am well, your son is well.” Perhaps Fanny had also heard rumours about Adelaide Correglio, commonly known as Dolly, the mistress Nelson now kept in Leghorn.

After he was injured in Santa Cruz and his arm was amputated, Nelson returned to England, where Fanny nursed him back to health. According to Lady Spencer, wife of the First Lord of the Admiralty, the couple were very much in love. Nelson told her that Fanny was beautiful and accomplished, and that her angelic tenderness toward him was beyond imagination. He even asked, against protocol, to be seated next to his wife at dinner.

In March 1798 Nelson was back at sea, chasing the French fleet through the Mediterranean. Needing permission to provision his fleet at Syracuse, he called upon the help of Lady Hamilton, wife of Sir William Hamilton, Ambassador to the court of the Kingdom of the two Sicilies, at Naples. She had a close relationship with Queen Carolina and was able to obtain the necessary letters from her. Nelson was thus able to sail on to Abu Qir Bay where the famous Battle of the Nile took place, wiping out all but two of the French fighting fleet.

On his return to Naples, Nelson found himself feted as a hero. He also found himself falling in love with Lady Hamilton. He wrote to Fanny: “What can I say of her and Sir William’s goodness to me. They are in fact with the exception of you and my dear father, the dearest friends I have in the world.”

A year passed, and Nelson showed no sign of coming back to England. Fanny suggested visiting him in Sicily, but Nelson wrote back to her saying that she would certainly regret leaving England to come to a wandering sailor who would be unable to look after her. He finally arrived back in England on November 6, 1800, accompanied by Sir William and Lady Hamilton. Fanny’s first meeting with Emma was not auspicious; Emma wrote that Fanny greeted her with “an antipathy not to be described.”

After her final separation from Nelson, Fanny continued to look after his father, who died in her presence at the age of 80. Nelson did not attend the funeral. Fanny’s son Josiah went on to marry one her godchildren, Frances Evans, and to become a rich stockbroker in Paris.

After Nelson’s death, Fanny divided her time between her home in Exmouth and her son’s home in Paris. One of her three grandchildren, Georgina, recounted that her grandmother slept with a miniature painting of Nelson under her pillow, which she always kissed before going to sleep. Once her grandmother had said to her: “When you are older, you too may know what it is to have a broken heart.”

Fanny died in 1831 at the age of 70, 27 years after her husband and 16 years after Lady Hamilton. She was buried at Littleham in Exeter, on the south coast of England, where there is a fine, carved, white marble stone to commemorate her passing. Perhaps, in death, Fanny did have her revenge over Emma Hamilton, who died in abject poverty in Calais with only a wooden cross, long since gone, to mark the place where her remains lay.