“Barcelona has honoured the art form of a little island,” says Peter Minshall. Minshall is a great talker, but he does not exaggerate. The principles and techniques which he has evolved in nearly two decades of work in the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival are now being applied to Bastille Day in Paris and this year’s Olympic Games. Five hundred years after Spain stumbled into the Caribbean, the Caribbean is raising its flag in Spain.

Barcelona in late July: the Spanish summer is as hot as the tropics. The warm air embraces sun-browned skins from almost every nation, the smell of summer flowers, the voices of birds in a busy downtown thoroughfare, the vast Barcelona docks and the 200-foot monument of Christopher Columbus which dominates the Plaza de la Paz on the seafront.

The Spanish port is full of echoes. The spired, beehived towers of the church of the Sagrada Familia (Holy Family), undertaken by the Catalonian architect Antonio Gaudi some hundred years ago, look almost like fancy clowns or fancy sailors from the Trinidad Carnival. No part of Barcelona is far from the sea and the ancient Mediterranean trade routes; this was a coast and a city Columbus and his successors knew well, as they opened up other oceans to other ports of Spain.

This year – in Barcelona for the Olympics, in the ’92 Expo in Seville, in Madrid’s Year of the Arts – Spain welcomes back to her shores the people and cultures dispersed over the new world since the Genoese sailor set sail under the Spanish flag. Among them is a Trinidadian sailor, Harold La Borde and his family, who has been sailing Columbus’s route eastward, from the new world back to the old; and a controversial designer bringing Caribbean Carnival techniques to the ritual of the Olympics.

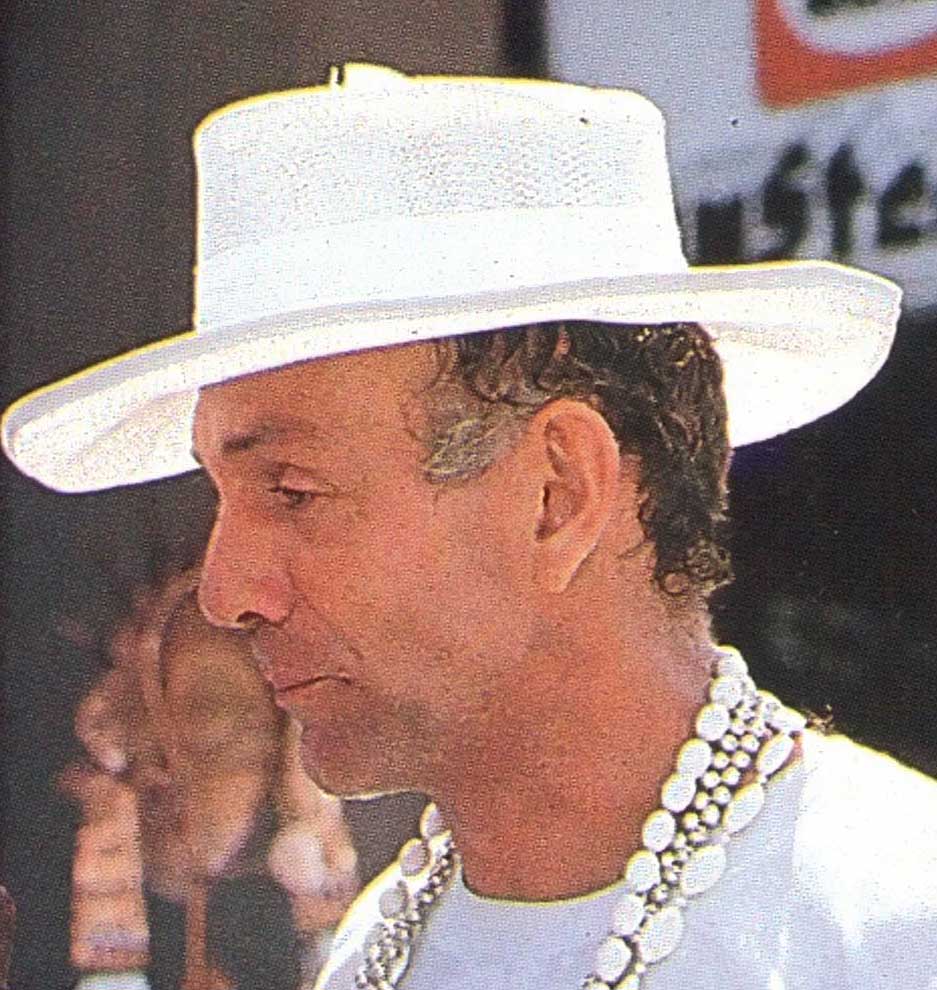

Peter Minshall, now 51 and the most talked-about artist in Trinidad and Tobago’s mas (Carnival), spent a year in Spain designing part of the spectacle that launched the Olympic Games on July 25 for the 65,000 people in the Olympic stadium and hundreds of millions watching on television. On the instigation of the Spanish conceptual artist Miralda, and on the strength of his portfolio in street spectacle Minshall was engaged in July 1991 to be part of the design team.

Trinidad and Tobago’s Carnival is a vast street festival incorporating the music of steelbands and calypso and thematic costumed bands. Minshall’s involvement in it lies at the root of his art. Mas (from mask or masquerade) is the multimedia, multi-dimensional art form which provides the artist with his palette. In 1991, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of the West Indies in recognition of his contribution to mas as an art form. More than any other artist, Minshall uses mas and its culture to create statements of universal concern. More than anyone else, Minshall has moved the art of Carnival design into choreography.

At 13, Minshall made and played an African Witch Doctor in the Carnival. Another time, disguised in his sister’s debutante gown, covered from mask to glove to high-heeled shoes, he gloried in the liberation of the mask. Playing and seeing others play their mas-bats, jab-jabs (diable or devil), fancy sailors, pierrot grenades – he understood instinctively its power.

His father told him a story about a traditional mas character, the pierrot grenade a clown whose costume is a robe of rags, multi-coloured strips of cloth. “The strips of cloth were layered with colours and little mirrors overlapping each other, so that when (the pierrot) moved he would make the cloth dance, and you would see a flash of this, a flash of that. If my work has been about any one thing, it has been an effort to marry structure with the dancing human form, to make the cloth dance, and through this dance, to speak.

Later he observed the simple old Trinidad Carnival bat. To Minshall the bat was “the most kinetic and alive of all traditional forms. I took him apart and put him back together again, and tried to find out how to make the cloth dance.

The bat has cloth wings, supported by canes held in the masquerader’s hand’s extended into a webbed shape by a few cane ribs, and attached to the feet, as are the wings of the actual creature. All this Minshall remembered when he had to find solutions for dancers in the ballet in London, and later on when, on his mother’s command, he set out to create a costume for his sister that would be outstanding enough to win her the major carnival competitions.

Land of the Hummingbird was Minshall’s Carnival debut in 1974. “At first she looked like nothing,” he remembers, “just a little blue and turquoise triangle, bobbing along among those grand plumed and glittering chariots, a little tent bobbling along. And then, the hummingbird burst into life, like a sapphire exploding . . .” The cloth had begun to dance.

Minshall the masman draws on every tradition of theatre and dance. “The direct influences for my work come from across all the arts and from my experience of human affairs. From Star Wars to this Francis Bacon, from Milton to Matisse, from Alvin Alley to Japanese dance, from ancient history to the morning newspapers: terrorism, television, religious fanaticism, racism, pollution the nuclear bomb.”

In 1975, after designing a band for London’s Notting Hill Carnival, he was approached by the Carnival bandleader Stephen Lee Heung in Trinidad to design something profound for his band, in the face of the new fantasy concerts that had been introduced since the late sixties. They agreed that it should be Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost.

The result was a band that became the watershed in contemporary mas, presenting (as one commentator of the day put it) “a formidable challenge to all designers, to all mas men … It is doubtful that the work of any single individual has had so instantaneous and so searing an impact on the consciousness of an entire country.”

The influences of Minshall’s theatre design training were evident, but more obvious still was the desire of the designer to integrate the best memories of his childhood carnivals with the best interests of the masquerader. “Mas,” Minshall insisted, “is a visual form of communication. It is not acting, it is play.” And a carnival band “is a whole incredible kinetic form-you have music, you have colour. It is not mechanical, it is alive . . . As you listen to music, you look at a band.”

Paradise Lost began with the banners of hell, carried by the Hellhounds in Pandemonium: fireflies, fallen angels and a burning lake created by a red canopy of cloth carried on poles, “danced” by the pole bearers. This particular dancing cloth has been used and developed many times since in Minshall productions: in River, in the canopy over Mancrab, in the dancing cloths of Tantana. Wings also featured prominently in Paradise, on the archangels, the birds and the butterflies; they were explored in Zodiac, and exploded in the band of 3,000 butterflies, Papillon.

By 1982 the streets of Port of Spain were full of butterflies with 12-foot wing spans, and Minshall had become something of a cult figure. He had created a Carnival of the Sea (1979), a Danse Macabre (1980), and in Jungle Fever (1981) had introduced another innovation music specially dedicated to the band’s theme.

In all these bands, the dark side of life contrasted with the lightheadedness and lightheartedness of Carnival: the malevolent transvestite Mother Earth in 1978; the cynical commentary on the futility of human life and endeavour in Danse Macabre, also seen as an environmental statement; and the inseparable Sacred and Profane, two sides of the same butterfly’s wings, in Papillon. The artist’s need to make relevant and poignant statements through his art climaxed in a trilogy, a three-year epic that included the creation and publication of Minshall’s original folk story Callaloo and de Crab. It started in 1983 with River, evolved through Callaloo in 1984, and culminated in the ultimate band clash in The Golden Calabash (1985). The art form was being remade by the artist.

“Trinidad Carnival,” Minshall says, “is a form of theatre, except that the costume assumes dominance, so what you wear is no longer a costume. It becomes a sculpture, whether it is a puppet or a great set of wings, and once you put a human being into it, it begins to dance. This is my discipline. I have the streets, the hot midday sun. I have 2,000 to 3,000 people moving to music. And I put colours, shapes and form on these people, and they pass in front- of the viewer like a visual symphony. The artist in carnival becomes a medium through which people express themselves.”

And like a play or a symphony Minshall’s mas began to present thematic development. In River the all-white gowns of the masqueraders presented a regal, solemn confluence on Monday, the first day of the mas. A rainbow cloth canopy was borne on poles over the band. The next day, the river was awash with colour as confetti and bright dyes were sprayed on the pure white in a frenzy of bacchanalian abandon. The pure Washerwoman, queen of the band, was bathed in blood in a symbolic rape by the evil, mechanical/technological Mancrab. The role of masmaker, more fully defined, was becoming that of puppet-master and choreographer.

The following year in Callaloo, the sequel to River, the costuming became, according to Minshall, “an unprecedented conjunction of sculpture and dance – the dancing mobile.” Minshall encircled the faces of his masqueraders with moons, hoops of fibreglass to shape the fabric. “The challenge of mobility in mas is to transmit the movement of the performer to his apparel, to magnify it … so that the mas expresses the dance and the rhythm of the music can be read high in the air.”

“It was the process that yielded not only unprecedented kinetic forms,” wrote the commentator for Minshall’s post carnival exhibition in Britain’s Riverside Studios, “but the discovery and introduction of a whole range of structural materials and techniques that have become staple elements of mas construction: cane, fibreglass rods, the lightweight and strong hollow tapered poles (fishing rod blanks), acrylic tube, garden netting, foam packing materials, reflective, coloured and opalescent polyester film, cheesecloth and the aluminium backpack.” To this has been added corrugated cardboard (Jumbies, 1988), parachute silk, nylon and pure cotton.

In 1985 Minshall made a solemn statement with his Madame Hiroshima, a costume sculpture which led the peace march through Washington on the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Madame Hiroshima personified the power of the nuclear bomb. A voluptuous, demonic, male-as-female creature with a mushroom cloud over her skull/head, she was one of the main characters in Minshall’s double band The Golden Calabash in 1985.

Minshall’s two bands that year were The Lords of Light and The Princes of Darkness, the final act of the trilogy. The battle between them would determine the winner of the prized Golden Calabash.

By this time Minshall was gaining an international reputation as designer and creator of spectacular happenings, and was being commissioned for other epic presentations, such as the opening of the Pan American Games in Indianapolis in 1987. In 1990, his magnificent puppets were the main characters in the Jean-Michel Jarre concert for the Bastille Day celebrations in Paris. In his 1990 Tantana the idea of the dancing mobiles reached its most effective form yet: with the supercharacter or puppet sitting on his head, attached wrist to wrist and foot to foot, the puppeteer was dominated by the puppet, his every movement magnified to theatrical proportions.

Minshall’s first super-puppet was The Midnight Robber (1980). In 1987 came The Merry Monarch, a magnificent grinning gaudy skeleton with multi-coloured ribbon ribs and rainbow rasta locks. The idea was further explored in 1990 by the dancing duo Tantan and Saga Boy, two puppets 20 feet high, topped with heads scuplted by Luise Kimme, wearing designer garments by Meiling and played by Peter Samuel and Alyson Browne. Apart from their Bastille Day appearance Tantan and Saga Boy have performed in Japan, Barbados and Nîmes in France.

Busy in Barcelona for 1992 Carnival, and anxious to relate his work there to the Carnival 4,000 miles away, Minshall created through his tribe (as he calls his creative and performing group at home) a band called Barcelona, Port of Spain, playing on the words and the concept of two distinct but related ports of Spain.

In June, the Whitsun weekend found him in Nîmes, France, presenting Man and the Bull in six giant fans, 5.2 metres tall and decorated with over 75,000 sequins each. These performed in the opening Carnival parade and during the festival, central to which is the bullfight.

In July, Minshall’s Olympic tribute presented the Barcelona of Gaudi, La Rambla and the Mediterranean with passion and style. Welcoming and Catalonian, universal in intent, the idiom was nonetheless rooted in the other Port of Spain whose life and vitality so permeate this artist’s ideas.

For Minshall, the most significant element in the art of mas is “the participation of people in the work of art.” “The masman depends on a family and a tribe. The family and the tribe depend on the masman. In no other discipline that I know does the artist have such a direct relationship with the community in which he does his work.” He paraphrases Lorca, who defined art as a cup filled at the well of the people, to be given back to them.

In 1993, Spain moves to Port of Spain for The Honeymoon, a Carnival collaboration with Miralda, who has already been working on a marriage of the Columbus statue in Barcelona’s Plaza de la Paz and the Statue of Liberty in New York (he has already toured the USA with Liberty’s wedding dress, rings and lingerie; the idea, so far unfulfilled, was to lower the wedding dress onto Liberty from a helicopter).

Minshall has already revolutionised Trinidad mas, by turning Carnival bands into raw material for a choreographer, and by using them to create contemporary myth about the nature of good and evil. His champions at home are legion; so are his detractors, who cannot stand the daring changes he has brought to the traditional crafts of Carnival. Now, he is applying the lessons he has learned – how to make the cloth dance – on the grandest of international stages: a new world of design invigorating the old.