My childhood memories of a summer in St Lucia have never left me. As a six-year-old from London, being suddenly transported from cold, grey streets to lush, rampant nature and a vibrant, jocular culture left indelible images emblazoned on my mind. It still surprises me how vividly I can see it all without even having to close my eyes.

Colourful minibuses crammed with people hurtling along winding roads. Ice-cream sellers wheeling wooden trolleys full of rum-and-raisin. The women in the Sulphur Springs bathing my baby sister in the bubbling volcanic water. Locals sternly warning us not to touch the manchineel trees. Giant breadfruit falling on the ground and rotting where they fell. Stalk-eyed crabs scuttling towards us on the beach at dusk. Eating mangoes in the sea. My first roti. Swimming all day, pounded by waves. Boys catching crayfish in the stream. The hammering of the rain on the galvanised roof.

It was the summer of 1986, and my mother took me and my siblings on our first and only family holiday outside Europe. Normally, our summers meant packing our car with camping equipment, crossing the English Channel, and driving down to the south of France for two weeks in a tent.

In St Lucia, we stayed for the entire school holiday in a house with a small pig farm on a piece of verdant, overgrown land overlooking Vieux Fort. The house belonged to my mother’s friend’s father. My mum had managed to scrape together enough money for our plane tickets on the understanding that we had a free roof over our heads, not too far from a beach. As it turned out, the beach was a good half-hour’s walk every morning across open fields, where my brother would invariably turn over a cowpat with his shoe, to inspect the underside.

Mum’s friend — a St Lucian woman named Rose, who lived in Stoke Newington in northeast London — was somewhat estranged from her father. When we arrived in Vieux Fort, we discovered why. He was wildly eccentric, bad-tempered, and a drinker. A comical looking character, stick-thin with wispy hair and thick glasses, “Jockey”, as he was known, would nudge wandering cows out of his path with the bumper of his rusty old jeep. One day, he sliced open the stomach of a dead field mouse and showed us its intestines to see what it had been feeding on. Another day, his dog Lucy got ill and, thinking she’d been poisoned, Jockey decided the antidote was more poison — with disastrous effects.

These dramas simply added to the wonder of that Antillean awakening in my young life. At an age when memories were beginning to be permanently formed, exposure to the delights of the Caribbean must have shaped my later desire to move to the region.

But it was over thirty years before I finally returned to St Lucia, intrigued to know if everything I’d heard about tourism development in the intervening decades had changed the island I remembered.

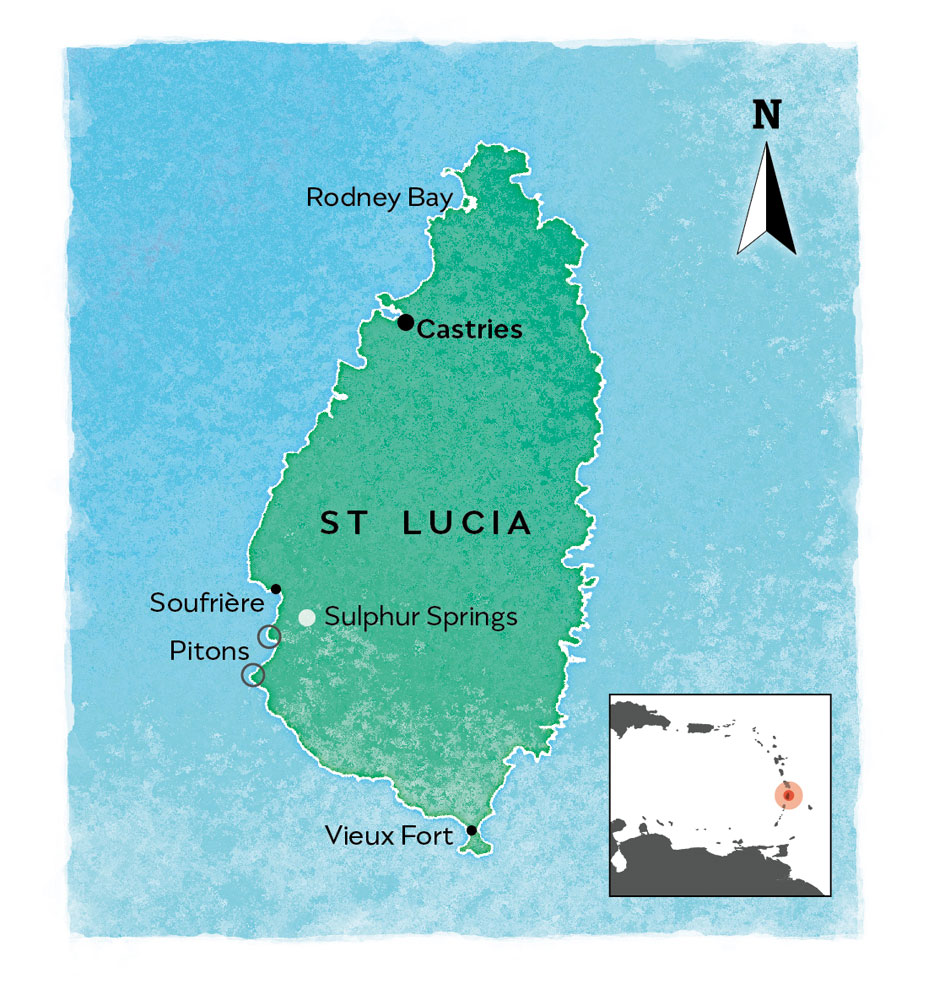

Arriving as a writer in my late thirties, being picked up by airport transfer and taken to the stunning boutique eco-resorts of Fond Doux and Ladera, nestled in the Pitons UNESCO World Heritage site, was vastly different to my childhood arrival.

Back then, after a long flight from London on which my travel-sick brother had puked on an old woman’s dress, we descended the plane down a wooden staircase on wheels and were hit by a humid tropical night air that filled my lungs and thoughts with the promise of adventure. We drove down pitch-black country lanes through swarms of fireflies to a house with a tin roof that became our home for the next six weeks.

The Vieux Fort I remembered was a place preserved not so much in aspic but in mango chutney. There’d been a constant chatter and murmur in the streets and a buzz in the air. Barefoot boys played football on pitches where the grass had worn thin, whooping and crying out. Drivers tooted hellos. The smell of curried meat wafted all about.

Had this all gone, I wondered? Vanished beneath golf courses, all-inclusive resorts, and marinas? Before my trip, I spoke to Anna Walcott-Hardy, daughter of St Lucia’s most celebrated author, the late Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott, who told me Vieux Fort was one of the few places left that kept its “old-world magic.”

I’d retained an image of its rugged fields with small cow herds grazing, houses dotted over gently rising hills, rivers overflowing in the heavy rain, and streams that trickled through overgrown wildernesses. Back then, the virtually empty beaches had strong waves but no tourists. At weekends, locals came to play volleyball. From behind Jockey’s house, we could see the airport and the jumbo jets slowly descending from the sky onto the solitary landing strip. We would play a game, first to spot if the plane was a Pan Am or TWA — airlines from a bygone age.

Returning as an adult, I was pleased to see Vieux Fort still encased in a metaphorical preserve. Unlike Rodney Bay, with its shopping mall and buses dropping off British, Canadian, and American tourists, or Soufrière, where the cinema where I once saw a karate film had been turned into a backpackers’ bar, or even Castries, where cruise ships the size of palaces disgorge flip-flopped holidaymakers in search of fridge magnets, Vieux Fort is still a town set up for local people going about their daily business.

Along Clarke Street, the main road running downtown from the airport, are solicitors’ firms, beauty parlours, mobile phone shops, barbershops, and just a handful of food places. The Food Hut is a wooden shack painted lime green and run by a woman named Antonia and her friendly staff. I stopped to watch the world go by over a hearty lunch of stew pork washed down with the local Piton beer.

After two days dining at places like Boucan in Hotel Chocolat (where the menu is entirely chocolate-based) and breakfasting at Ladera, overlooking acres of spectacular rainforest in Soufrière, Antonia’s was a different kind of fare — this was soul food.

Vieux Fort doesn’t just look, feel, and taste different to the rest of the island, it sounds it, too. You won’t hear hustlers asking if you want a jet ski or boat ride. Locals are friendly but uninterested in the tourist trade. You’ll derive more entertainment in ten minutes standing around the taxi stand listening to the drivers gossip or play dominoes than in an entire week in a foreign-owned resort.

I wandered down to the fishing port, where young men scaled, cleaned, and gutted fish whose names were written on numbered stalls in Creole: “taza” (kingfish), “bétjin” (barracuda), “chatou” (octopus), “kamo” (freshwater fish), “lanbi” (conch), and “ton” (tuna).

I passed one or two small churches, but nothing like the abundance of evangelical church halls you see travelling through the steep inland hills, with names like Sisters of the Sorrowful Mother Convent and Revival Tabernacle. Outside the beautiful white-and-carmine–painted edifice of St Paul’s Anglican Church I heard a man with a loudspeaker exclaiming jovially, “February is Black History Month — take down that picture of a white Jesus!”

With a tide of nostalgia beginning to flow, I decided to retrace my footsteps and see if I could find Jockey’s old house in the quiet backroads of La Resource.

“It’s by the cemetery,” people told me as I slowed down to ask directions. A beaming old lady handed me a bag of fruit that might have been sapotes, and pointed me onward through charming residential streets where the houses ranged from pretty to grandiose to ramshackle, until eventually I found a narrow footpath leading through soft grass and trees where a grey pony was tied up. At the end of the path was a house with a verandah, surrounded by overgrown gardens. Stacked-up chicken coops and creeping honeysuckle vines cluttered the scene.

I knew it was Jockey’s place, but it didn’t fit with the idyllic images I had stored away. I called out, but nobody came. Eventually a woman emerged from a house whose owners must have bought or annexed part of Jockey’s land. She told me Jockey’s brother lived there now, but he was out.

I wondered where the crayfish stream was, or the pigsty my brother would follow the farmhands to at six o’clock each morning to feed the pigs, smell their strangely satisfying stink, and scratch their hard, scaly, hairy backs with a stick.

What used to be open land all around the house now had several houses built nearby. My memories were of being far from any other human contact. Perhaps it was the vantage point of adulthood versus youth. Further down the road were even a couple of parlour shops.

Driving down a dusty track into a cul-de-sac, I saw houses made of unfinished breezeblock with broken windows and rusting corrugated iron surrounding them, acting as makeshift perimeter fences. The billionaires with their yachts and multinational travel companies to the north were notably absent in the south.

And yet the tranquillity of the place was something marvellous. As I made my way back to the airport to check in, I passed families sitting on their front steps, bougainvillea bushes blowing back and forth in the breeze, a winding creek passing below a bridge, mechanics taking a break in the mid-afternoon sun, schoolchildren laughing in a playground. I realised that here indeed remained that magical old world that Derek Walcott’s daughter spoke of.