On May 30, 1845, a small sailing ship of 415 tonnes, the Fatel Rozack, tied up at the lighthouse jetty in Port of Spain, Trinidad after a 96-day voyage from Calcutta, around the southern tip of Africa and across the southern Atlantic.

On board were 217 Indians, under the impression that they were heading for a better life on the sugar estates of Trinidad. Most were under 30, and all but five were men. The eldest, Ruchparr, was 40; the youngest was a girl of four, Faizan. Five had died on the voyage; but not to worry, the Port of Spain Gazette reported, “the general appearance of the people is healthy”.

In British Guiana (now Guyana), the importation of Indian labour had begun seven years earlier. But this was a new experience for Trinidad. People crowded the jetty to watch; planters, desperate for dependable labour, waited to claim their new workers.

Over the next 72 years, 143,939 Indian labourers were shipped to Trinidad; about 240,000 were sent to Guyana (then British Guiana), 36,000 to Jamaica, and smaller numbers to St Vincent, Grenada, St Lucia and Martinique. They came from large areas of India – notably Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Oudh and Bengal – through the port of Calcutta (and in the early years through Madras). Most were Hindu, with a minority of Muslims. They were recruited by unscrupulous sub-agents working on commission for a British-appointed Emigration Agent based in Calcutta, armed with requisitions from the Caribbean planters.

They were easy prey for the recruiters. It was not hard to dream of escaping from the harsh economic conditions of India in the 1840s: drought, debt, famine, low living standards, political tensions. Recruiters encouraged people to put their thumbprints on the contract papers, telling them stories of lands across the ocean littered with gold. Some were simply kidnapped; others were glad to flee from hunger, or from the clutches of Indian moneylenders. Many single women wanted release from the shame of prostitution or widowhood, or from the brutality of their menfolk. They bearded the ships at Calcutta, expecting new lives.

The 11,000-mile voyage, first under sail and later in steamships, took an average of 100 days, and mortality rates in the early years were high. Of the nearly 144,000 who landed in Trinidad, only 29,448 returned to India. By 1871, Indians formed a quarter of Trinidad’s population. By 1990, by a small majority, their descendants had become the single largest ethnic group in Trinidad and Tobago, as they had long been in Guyana.

In 1838, the Africans who for two centuries had been shipped across the Atlantic in their millions to work the colonial sugar plantations of the Caribbean were finally emancipated. For the plantations, the immediate result was a labour crisis: liberated slaves left the plantations in droves, or demanded proper wages for their work.

The British tried importing labour from neighbouring islands, from the United States, free Africans from Sierra Leone; they lured French and German immigrants with talk of high wages, recruited Portuguese workers from Madeira, shipped labour across the globe from China. But nothing worked; none of these groups settled down to service the vital sugar estates with the necessary docility. Eventually the British turned to India. India was already a British colony, which simplified arrangements; there was plenty of spare labour accustomed to Caribbean-like conditions; and it was a lot cheaper than China.

The first shiploads arrived in Guiana in 1838, followed in 1845, 150 years ago, by the Fatel Rozack in Trinidad.

At first, there was little thought of a permanent Indian population for the Caribbean. This was short-term migrant labour; there were to be free return passages. But gradually the estates had that changed. They wanted control of their workers, they wanted sanctions against desertion, control of movement. And they got it.

Trinidad soon established a tough indentureship programme: recruits had to put in ten years’ labour to earn their passage home, or buy themselves out with a lump sum or special tax payments. They had to carry passes when off the estate; there were jail terms for offenders. The return passage was replaced with grants of state land.

The early days of the scheme were harsh. “Take a large factory in Manchester or Birmingham,” wrote the English commentator Edward Jenkins in 1871, “build a wall round it, shut in its people from all intercourse with the outside world, keep them in absolute heathen ignorance and get all the work you can get out of them . . . and you would have constituted a little community resembling a sugar estate village in British Guiana.

Nor did conditions improve much over the years. Sixty years later, in the 1930s, Jock Campbell (later Lord Campbell, Chairman of the British sugar giant Booker), was devastated by what he saw in British Guiana, where he inherited a sugar fortune. “The condition in which past members of my family had pursued profits and made considerable fortunes came as a great shock to me. The Indians lived in the same disgusting circumstances as farm animals.”

The British historian, Hugh Tinker, saw it as “a new system of slavery”. Suicide, disease, degrading living conditions, repressive terms of employment, political restriction, low wages, back-breaking labour in the canefields, a hostile environment, all this formed the fabric of the “new life in the Caribbean. Hindu and Muslim marriages, for example, were not officially recognised until the 1940s, causing generations of Indians to live their lives in technical illegitimacy.

How to survive was the primary concern. One way was through the maintaining of tradition and identity, and sometimes using it as a way of confronting the colonial authorities. The Muslim Hosay festival is a good example.

During the first ten days of Mohurram (the first month of the Islamic calendar), Shi’ite Muslims commemorate the martyrdom of the grandsons of the Prophet Mohammed. Hundreds of worshippers and participants of all ethnic groups would follow the procession of their tadjahs (huge decorated replicas of the martyrs’ tomb) to the riverbank.

It was a religious ceremony, but also an occasion for drinking and dancing, especially among those who were not devout Muslims – Hindus, Christian Africans and Chinese immigrants. The participants vented their frustration against the colonial police and other personnel.

During the 1884 Hosay in San Fernando, Trinidad, rioting broke out; more than 100 people were shot, and 12 died. By 1904, Hosay was a full-blown, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural affair full of defiance; the colonial authorities condemned it for having “gradually degenerated into a saturnalia in which Hindus, Mohammedans and Negroes mingle promiscuously and rum and ganja add to the religious fervour of the processionists.”

Survival for the Indians took other non-violent forms. They maintained their diet of rice, dhal(lentils), roti and, of course, curry. Indians gave the Caribbean a taste for curry, and it is this taste which, some say, unites the region more effectively than any edict from governments or other official bodies.

The Indians also strove to replicate, as far as possible, scenes of village India within the environment of the plantation and later on their own lands. They kept cows. They planted rice and garden vegetables. They introduced Indian trees and shrubs to make their landscape bearable. They struggled to maintain a strong family structure.

Men and women laboured ceaselessly, ate little and saved their money to benefit their children. They sacrificed health and nutrition so that their children could thrive. There is hardly a testimony from colonial officials of the day which does not dwell on the dedication of Indians. When Walter Rock, a District Commissioner in British Guiana, spoke of Indians as a “thrifty, persevering and hardworking lot of families”, he was stating a view which had become standard.

A few Indians achieved spectacular success by their industriousness. Resoul Maraj, for instance, the first known millionaire in the region, started off in the 1880s as a “coolie” in British Guiana; he invested his indenture wages in a horse and cart, starting a humble transport business. By 1917 he owned a general store.

He diversified into rice production, eventually buying up four abandoned plantations and exporting rice, cocoa, coffee, coconuts and coconut oil. Rich as he was, he never forsook the needy and unfortunate. When he died in 1929, the Daily Argosy described him as a man “of a very genial disposition, and very much loved by the poor of all races on account of his benevolence.”

But it was in the field of religion that the cane-cutters proved most resistant to colonial transformation. Faced with the apparatus of Christian missionary endeavour, they argued the articles of their faith and defended Hinduism and Islam. H.P.V. Bronkhurst, a 19th-century Methodist preacher, confessed to his lack of success in winning Indians over to Christianity. “In preaching to the coolies whether in sugar estates, in the yards, villages and publicly, in large numbers or privately in their houses, we meet with endless objections brought before us again and again.”

In Trinidad, the Canadian Mission schools which opened as early as 1868 had more success in converting and westernising Indians – by 1921, 11.8% were Christian (though in that same year, four years after the indentureship programme ended, there were only 187 Indians who had entered the official or professional classes).

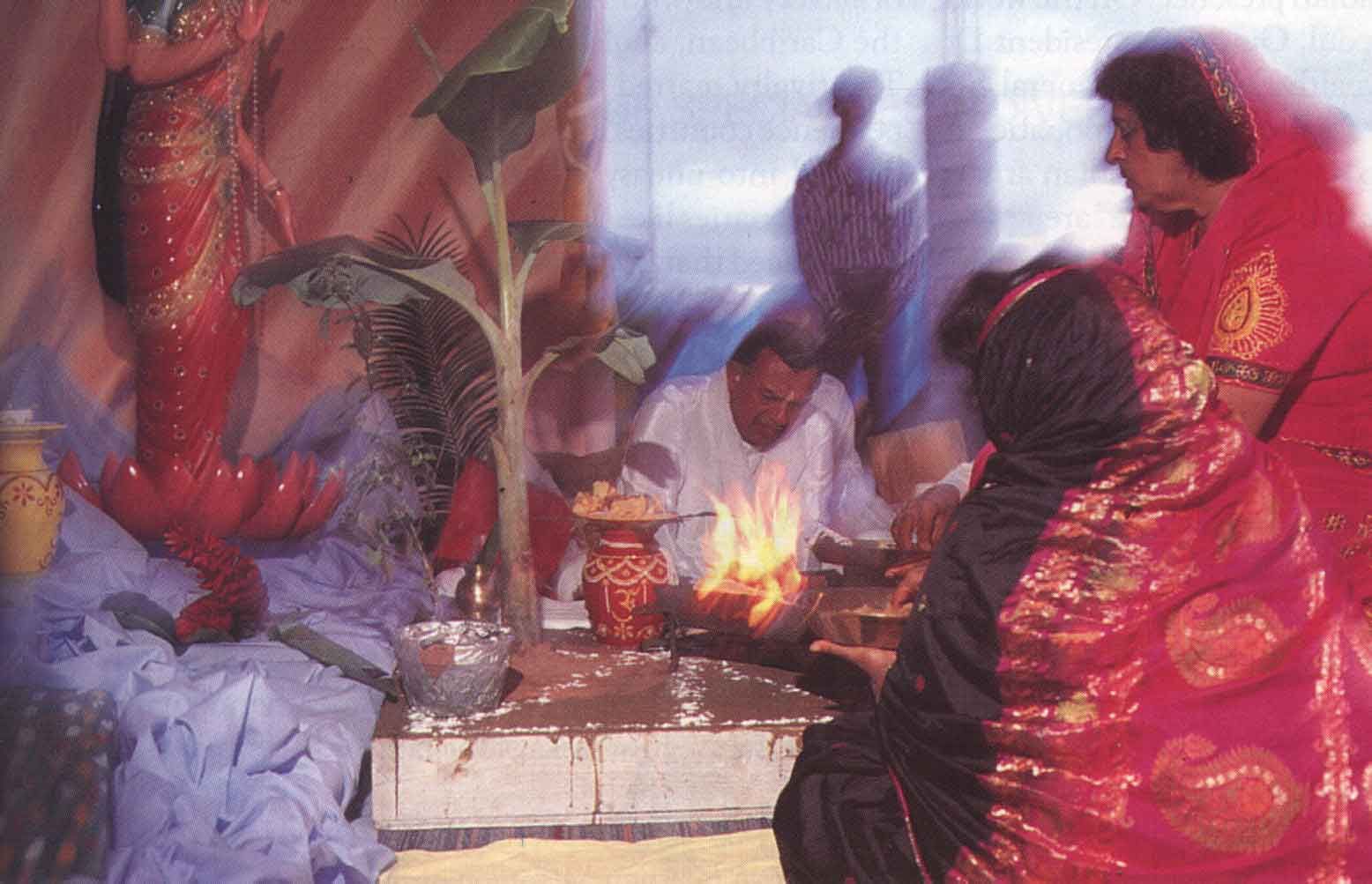

Indians built mosques and temples to sustain their religions. Holy men from India visited the Caribbean colonies regularly to replenish the faiths of the indentured labourers. They supplemented the efforts of pundits and imams from within the workforce (for among the half-million shipped to the Caribbean region were people of priestly status).

Muslims organised recitals from the Koran in mosque and bottom-house, teaching the children Urdu and Arabic and selecting a few to be returned to India for religious training. Hindus celebrated Divali (the ceremony of lights, in devotion to the Goddess Lakshmi) and dramatised the life of lord Rama and Lord Krishna as narrated in the sacred texts of the Ramayana.

If the 19th and early 20th century phases of Indian settlement were characterised by resistance to the values of the plantocracy, the modern period has seen rapid creolisation. In Trinidad, the exploitation of oil resources led to rapid urbanisation and semi-industrialisation. Indians moved from their garden patches to seek their fortunes in the factory and the office. By the turn of the century there was an established Indian community living in villages and settlements; in the 1940s and 1950s a professional class formed, comprising doctors, lawyers, teachers, civil servants, politicians and merchants.

Today, there is hardly an area of Caribbean culture and society – literature, academia, politics, economics, business – that has not been affected by the Indian presence. On the world stage, think of novelist V.S. Naipaul, Guyanese president Dr Cheddi Jagan, former Commonwealth Secretary-General Sir Shridath Ramphal; the success of calypsonian Droopatie in Trinidad and Tobago shows the extent to which Indian artists have established themselves in the national, “creole” arena. No less crucial to Caribbean progress are the hundreds of thousands whose agricultural skills saved the sugar industries of Trinidad and Guyana, and still produce the bulk of our locally-grown food.

As George Lamming, the Barbadian novelist, put it: “The Caribbean is our own experiment in a unique expression of human civilisation, and there can be no creative discovery of this civilisation without the central and informing influence of the Indian presence. There can be no history of Trinidad and Guyana that is not also a history of the humanisation of those landscapes by Indian labour.”

Which brings me to the activity dear to all West Indian hearts – the game of cricket. George Lamming’s assessment of the Indian dimension to Caribbean life is best supported, to my mind, by the career of the cricketer Rohan Kanhai. Born on a sugar estate in colonial Guiana, of peasant parentage, Kanhai rose to become a world-class batsman and captain of the West Indian cricket team. In his 79 test matches over nearly 20 years, he scored 6,227 runs, including 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries.

He was, according to C.L.R. James, the most electrifying batsman of his day, and was credited with single-handedly inventing a new sweep stroke. Clem Seecharan, in his book on Indo-Caribbean cricket, describes it as “a cross between a sweep and a hook, the execution of which required impeccable footwork, supreme timing, immense self-confidence and an instinctive sense of theatre.”

Even before Kanhai became a household name in the region and abroad, another Indian, the Trinidadian Sonny Ramadhin, was terrorising the world’s batsmen by the cunning of his spin bowling.

Ramadhin was also from humble origins, and wholly untutored. He made his international debut in England in 1950, helping the West Indies to their first Test and series victory against England. He dominated West Indian cricket at Test level for ten years, and still holds the world record for the most balls and overs bowled in a test match – 774 balls in 129 overs against England at Edgbaston in 1957.

Indian progress, however, has always been controversial. Early Afro-Caribbean leaders in the 1920s and 1930s expressed their fear of Indian political domination, in view of the rapidly growing Indian populations. The Africans, who had died in such appalling numbers in the period of slavery and who had made stupendous sacrifices in shaping the Caribbean, could not tolerate the prospect of Indian rule. The rivalry marred the efforts at decolonisation, and at independence countries like Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago were divided into uneasy ethnic enclaves. Caribbean intellectuals and visionaries like Walter Rodney and George Lamming have long argued that, for healing to occur, we have to know who we are, where we came from, how we evolved.

The narratives of the African experience of the Caribbean are still too few and relatively recent; those of the Indians have barely begun to be researched and written. The histories of the other peoples who helped to shape today’s Caribbean (the native Amerindians, the Chinese, the Portuguese) are only now beginning to emerge.

Colonial education systems ensured that we knew more about the feats of outsiders than we knew about ourselves. How to remember the past so as to avoid dismemberment in the future is one of the greatest tasks of the late 20th-century Caribbean.