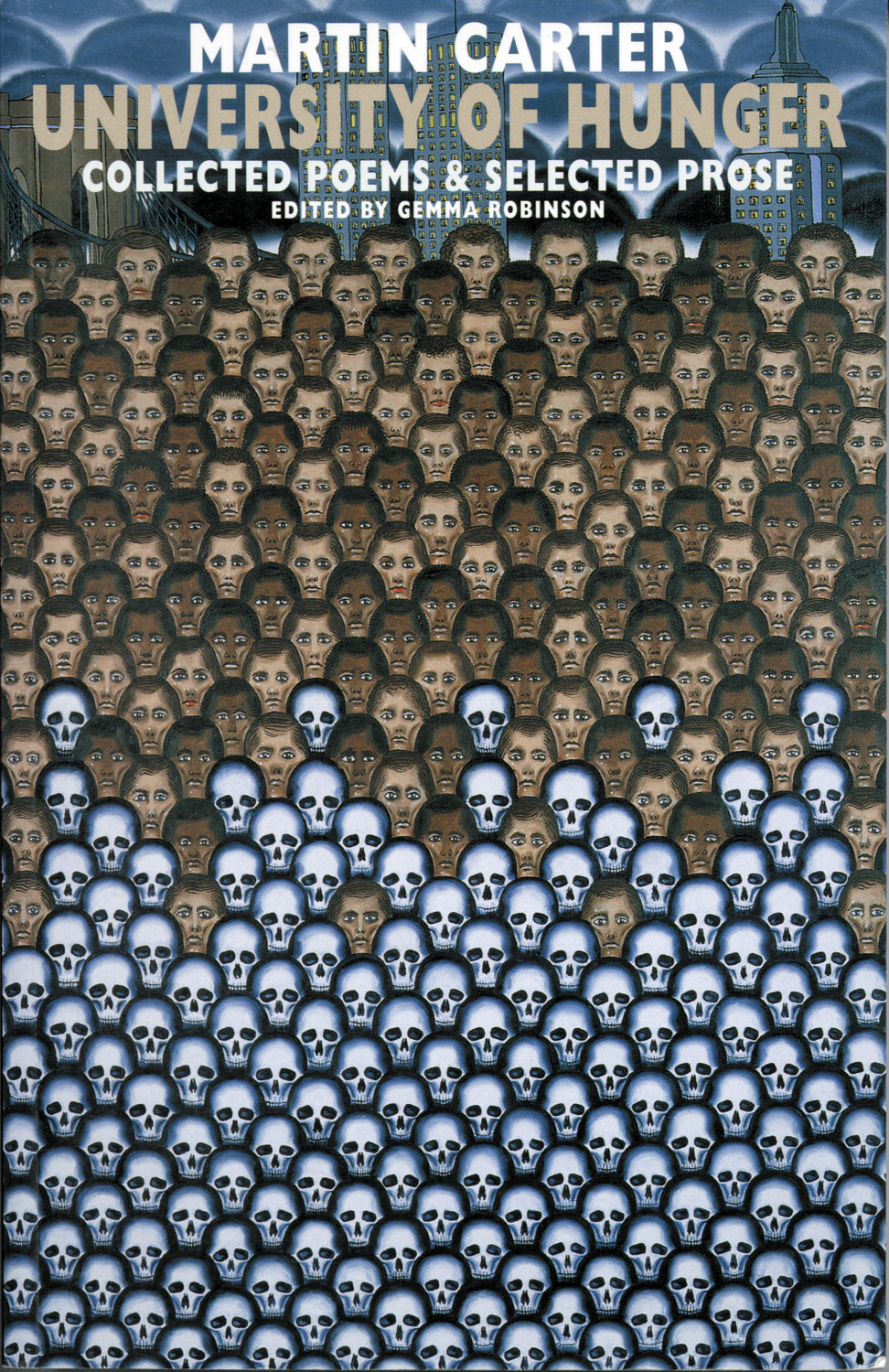

University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose

Martin Carter, ed. Gemma Robinson (Bloodaxe Books, ISBN 1-85224-710-X, 320 pp)

For the individual reader, poetry’s true avoirdupois is known only to the heart’s shivering scales. But how do we measure a poet’s enduring worth to a society, a nation, a people? One way is to count his phrases and lines that have entered the common language, that ordinary men and women have come to think of as their own, that seem, as all true poetry seems, to have found a way to express something crucial and otherwise inexpressible. By this standard there is no West Indian poet, not even Derek Walcott, whose poems have been so vitally important to so many as Martin Carter’s.

The British literary scholar Stewart Brown tells the story of a reading Carter gave in London in 1991. Many in the audience were Guyanese expatriates of no particularly literary bent. “As he read from those poems,” Brown remembers, “that audience began to recite them with him — not to read them from a book, but to recite them from memory.” For to read Carter’s poems is to encounter a sequence of lines that have become the everyday possessions of many ordinary people in Guyana and elsewhere in the Caribbean, possessions no less everyday for being lyrics of rare power and rhythm: “is the university of hunger the wide waste”; “Death must not find us thinking that we die”; “I come from the nigger yard of yesterday”.

After his death in 1997, Carter’s work fell not entirely but nearly out of print. It is a pleasing coincidence that 2006 brings two separate new editions of his poems. Ian McDonald and Stewart Brown’s Poems by Martin Carter, based on the text of the 1997 Selected Poems, will shortly arrive from Macmillan; and University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose, edited by the young British Carter scholar Gemma Robinson, appeared a few months ago on the list of the eminent poetry publishers Bloodaxe.

University of Hunger is the most comprehensive Carter edition yet, collecting 169 poems, including every one of his published poems and some previously unpublished. It is scrupulously annotated, providing for each poem information about surviving manuscripts or typescripts, place and circumstances of first publication, explication of puzzling references, and major variant readings, so that the reader can follow a poem’s revisions between successive appearances in print. Few Caribbean writers have enjoyed such careful editorial attention, and University of Hunger will be the definitive Carter for the foreseeable future. It is usefully fleshed out with a selection of fifteen essays on anti-colonialism, race, the meaning of nationhood, and art and literature, and Robinson has written a lively introduction combining biography with thoughtful literary analysis.

For longtime readers of Carter, this is a chance to engage with the poems afresh, to see at once the whole shape of the arc of his poetic career. Carter’s earliest work is still his best known: the flag-waving poems written in the 1950s around the time of the first electoral victory of the People’s Progressive Party (of which Carter was then a member), the short experiment in self-government in pre-independence British Guiana, the state of emergency of 1953 (when Carter was arrested) and the occupation of Georgetown by British troops when the colonial authorities decided the PPP was a Communist threat. The poems of The Hill of Fire Glows Red (1951) and Poems of Resistance (1954) express better than any politician’s speeches the hunger for freedom that drove the independence activists of British Guiana — and, for that matter, the rest of the British West Indies. But they also express a more subtle but no less visceral hunger for self-understanding — self as human being, as citizen, as poet.

Poems of Resistance from British Guiana — the full title of the book’s original edition — was published by Lawrence and Wishart, a prominent firm of left-wing London publishers, and eventually translated into Russian and Chinese. It won Carter the reputation of a “political poet”. It’s true that Carter’s was always, in Gemma Robinson’s phrase, “a poetry of involvement”, but the “political” badge, attracting some readers and repelling others, also obscured his real lyrical gifts and the keen spiritual curiosity that always animated his poems. Early protest poems like “Not I with This Torn Shirt” and “A Banner for the Revolution” hammered hard at the bells of social change. Later, quieter poems, like “Our Time”, which opens his Poems of Affinity (1980), show us that Carter’s delicate, fine ear was inseparable from his delicate, fine moral sensibility.

These poems are often angry, often inspiring; just as often they are puzzling and melancholy. Robinson reminds us that Walcott found in Carter’s poems a quality he called “tenderness”. It is a good word for a poet who could describe how “a sweet child smiling with innocence / still wonders why a frown is not so ugly”. But these poems are never comforting. The urgency of Carter’s drive to understand the imperfect world left no room for comfort.

— Nicholas Laughlin

Our time

The more the men of our time we are

the more our time is. But always

we have been somewhere else. Muttering

our mouths like holes in the mud

at the bottom of trenches. Looking

for what is not anywhere, or certain.

Is it only just a misfortune

to be as we are; bad luck

carefully chosen? In parallel seasons

if rain is any hour; if trees abandon

wind, what of the others? Badly abused

we fail to curse. Our fury pleads.

Yet fury should be fire; if not light.

And what is the mother of fury

if not ours. For any man

and for any time, one dream

is enough. This is true.

— Martin Carter

Eric Williams and the Making of the Modern Caribbean

Colin A. Palmer (Ian Randle Publishers/University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 976-637-244-6, 354 pp)

“A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma” — Winston Churchill’s famous description of Stalinist Russia aptly summarises the life and career of Eric Williams, pioneering historian, anticolonial theorist, and first prime minister of independent Trinidad and Tobago. Twenty-five years after Williams’s death, we are still waiting for a scrupulously researched full-scale biography; it is one of the major omissions in contemporary Caribbean scholarship. Colin Palmer’s new book — part political history, part intellectual biography — is not that long-awaited grand tome, but it is an insightful, rigorous study of Williams’s thought and action in the key period between 1956, when he became chief minister of Trinidad and Tobago, and 1970, when the Black Power Revolt seriously challenged Williams’s authority and shook his political confidence. Palmer pays special attention to Williams’s struggle to assert sovereignty over Chaguaramas (site of a US military base since the Second World War), his relations with Africa, his involvement in the British Guiana crisis of the 1960s, and his wider role in anticolonial politics in the Anglophone Caribbean. “His personal limitations notwithstanding, Eric Williams was the greatest leader his people produced in the twentieth century,” Palmer writes. “His domination of the political arena, though at times halting and unsteady, was no historical accident.”

— Philip Sander

Iron Balloons: Hit Fiction from Jamaica’s Calabash Writer’s Workshop

ed. Colin Channer (Akashic Books, ISBN 1-933354-05-4, 281 pp)

The Calabash International Literary Festival, held in Treasure Beach in south-west Jamaica every May, is the centerpiece of what’s become perhaps the most successful (certainly the most savvy) movement in contemporary Caribbean letters. Steered by novelist Colin Channer and poet Kwame Dawes, the Calabash “brand” now extends to an intensive, free-form writing workshop based in Kingston and a series of books and pamphlets produced in partnership with several international publishers. In 2005 a Calabash Chapbook Series presented the work of six Calabash poets; now Iron Balloons does the same for six of the workshop’s fiction writers — Marlon James, Alwin Bully, A-dZiko Simba, Rudolph Wallace, Konrad Kirlew, Sharon Leach — whose stories are presented alongside contributions from some of the workshop’s instructors: Elizabeth Nunez, Kaylie Jones, Geoffrey Philp, and Channer and Dawes themselves. In his energetic introduction, Channer explains that Calabash models its modus operandi on Jamaica’s music industry, which for forty years has channelled the talents of Jamaicans of all social classes into international hits. Can they do the same for Jamaican writers? Well, the Calabash workshop has already scored one big hit: two years after he joined the fiction workshop in 2003, Marlon James’s debut novel John Crow’s Devil was in print in hard covers and racking up prize nominations.

— PS

Trinidad Carnival: Photographs by Jeffrey Chock

with text by Tony Hall, Hélène Bellour, Samuel Kinser, Karmenlara Seidman, and Kim Johnson (Medianet, ISBN 976951374-1, 190 pp)

Trinidad Carnival is essentially ephemeral. For two glorious, riotous days the streets are filled with bodies, colours, music, mud, feathers, voices, human beings transformed into creatures beautiful and ugly, ethereal and terrible, in a communal ritual both sacred and profane. Then on Ash Wednesday morning the garbage and broken pieces of costumes are carted away, and what survives are memories — and photographs.For close to thirty years, Jeffrey Chock has been photographing Trinidad Carnival, patiently manoeuvring through crowds, over barriers, across stages, and finding in the chaos images that, at their strongest, do far more than document. Spontaneous yet deliberate, finding the eerie in the pretty and the beautiful in the debased, and filled with faces transfigured by an emotion far more complicated than mere joy, the best of Chock’s photos embody Carnival’s true aesthetic (gritty east Port of Spain version). There are quietly comic images here, like a shot of a group of young masqueraders wolfing down their lunch in Woodford Square; there are images of great formal beauty; there are images of stick-fighters and panmen and blue devils that get the adrenaline pumping; and there are images, like the dramatised death of the Washerwoman from Peter Minshall’s 1983 band River, that leave you transfixed and speechless.

— PS