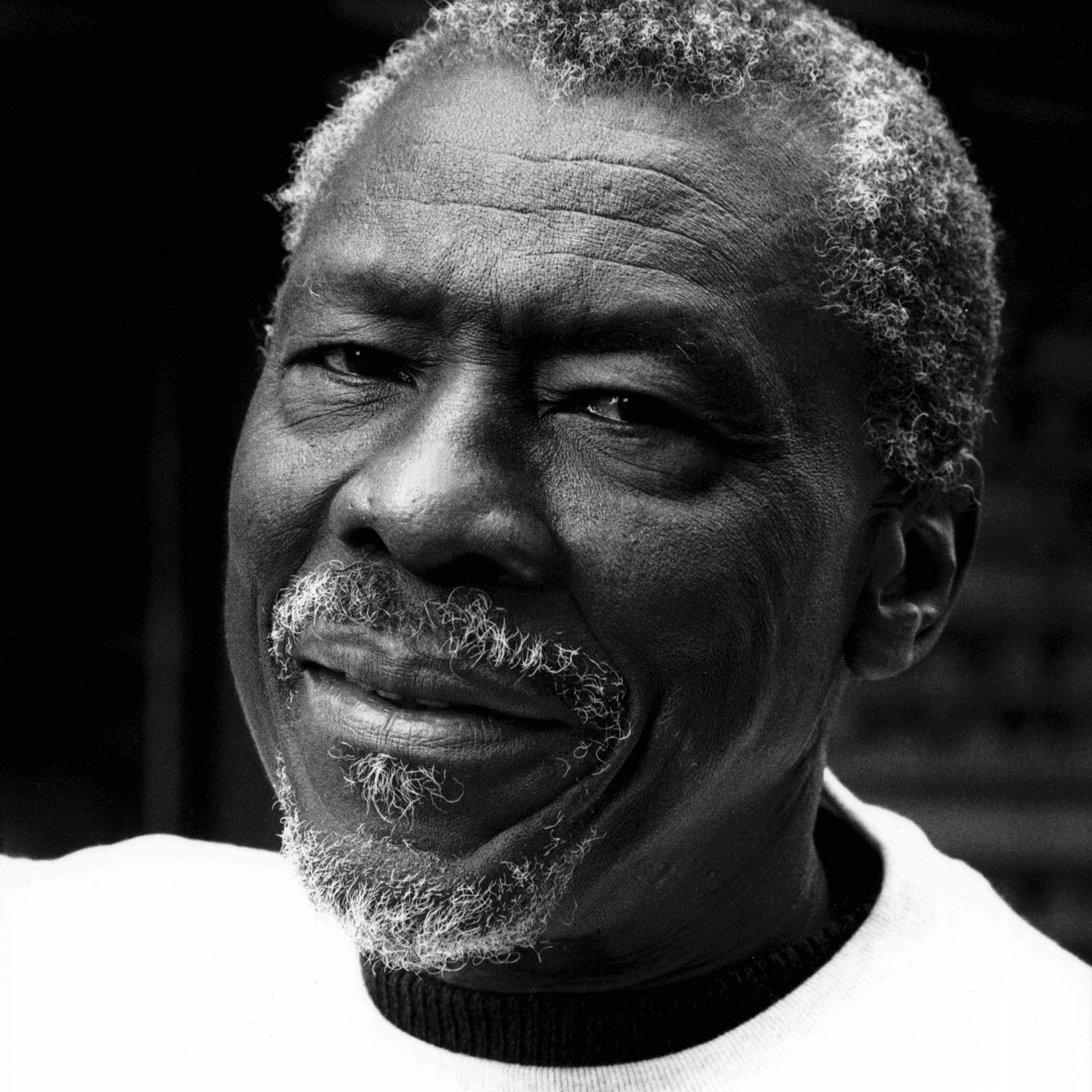

Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd, who died in May, aged 72, was one of the most important figures in Jamaican popular music for over 50 years, a legendary record producer who nurtured the career of nearly every internationally renowned reggae artist. He was one of the first producers to record local talent; he was an integral force in the development of ska, Jamaica’s first truly indigenous popular form; and he oversaw numerous musical innovations at his famed Studio One recording facility during the reggae, roots, and early dancehall phases. His contribution to the evolution of the island’s music is simply enormous.

Born in Kingston in 1932, Dodd spent some formative years in the eastern parish of St Thomas, before returning to the capital to learn cabinet-making and to train as an automobile mechanic in the Ford garage on Church Street. His father was a mason who helped build the Carib Theatre, a landmark building in the Kingston business district known as Cross Roads; in the early 1950s, Dodd’s mother ran Nanny’s Corner, a restaurant located at the busy downtown junction of Lawes Street and Ladd Lane, where customers were entertained by Billy Eckstein, Sarah Vaughan, Lionel Hampton, and Louis Jordain, played on the family’s Morphy Richards radio. In the early 1950s, Dodd worked as a farm labourer in the American South, and began contemplating an entry into the music business after seeing money being made at outdoor block parties. He returned to Jamaica with a collection of highly prized jazz and blues records, which made this entry possible.

From the late 1940s, the Jamaican music scene was based around sound systems, huge sets of portable equipment that played hot rhythm and blues for the masses at open-air dance events. In the early 1950s, the leading sound system was “Duke Reid the Trojan”, established by former policeman Arthur Reid, a close friend of Dodd’s parents. Dodd began to do guest spots spinning his rare records on Reid’s set, but became Reid’s biggest competitor by establishing “Sir Coxsone’s Downbeat” sound system, named in reference to a noted Yorkshire cricket batsman, whose skills in the field Dodd was said to emulate.

Dodd quickly rose to prominence, thanks to a superior selection of rhythm and blues and hard-to-find jazz discs; he also had toaster Count Machuki, a wisecracking DJ whose rhyming jive-talk helped ensure the set’s popularity. Sound system rivalry was particularly fierce in this era, and having the right men on your side could make or break a sound. Several internationally renowned figures worked for Dodd, including Prince Buster — a former boxer who staved off many attacks from Duke Reid’s henchmen before striking out on his own in 1957 — and Lee “Scratch” Perry, who began working for Dodd as a vocalist, talent scout, and general dogsbody in 1961.

In 1956, Dodd began recording local artists such as Bunny and Skully at the Federal studio, usually local versions of rhythm and blues. But an early hit, Theophilus Beckford’s Easy Snappin’, had a markedly different beat, pointing the way to the ska sound that Dodd would champion by the end of the decade. By the early 1960s, he ruled Jamaica with countless ska hits by Toots and the Maytals, the Gaylads, and the Jiving Juniors, while the Skatalites, Jamaica’s premier ska group, was formed at Dodd’s request to propagate the ska form islandwide.

In October 1963, Dodd opened the Jamaica Recording and Publishing Studio, close to the Carib Theatre at 13 Brentford Road. The site of a former nightclub called The End, the facility has always been referred to as Studio One. It was here that Dodd cut the first recordings by Bob Marley and the Wailers, whom he signed to an exclusive contract; he gave immeasurable guidance to the group, selecting Marley as leader and scoring several number-one hits with them. He acted as something of a surrogate father to Marley during this period, even giving him a place to live on the premises, and Marley actually met his future wife Rita at the space when Dodd gave Marley the task of coaching her harmony group, the Soulettes.

When the rocksteady form briefly supplanted ska in 1966, Dodd found Duke Reid overshadowing him, but when the new reggae style came to the fore in 1968, Coxsone was back on top, with enthralling recordings by the Heptones, the Abyssinians, Bob Andy, and Marcia Griffiths. In the early 1970s, Dodd was one of the first producers to release material proclaiming a Rastafarian worldview and speaking of black pride. Though he remained a devout Christian himself, cutting gospel music on Sundays for issue on his Tabernacle label, he often explained that aspects of the Rastafarian message made sense to him, which is why he permitted its free expression — unlike rivals like Duke Reid, who refused to issue material that made any reference to it.

Dodd subsequently brought Dennis Brown to prominence, and made innovative forays in the dub form, in conjunction with his chief engineer, Sylvan Morris. Though re-cuts of Studio One hit rhythms recorded at the rival Channel One and Joe Gibbs studios later found greater favour, he beat the imposters at their own game with a Studio One renaissance in 1979, voicing new material on re-vamped rhythms with proto-dancehall singers such as Sugar Minott, Johnny Osbourne, and Freddy McGregor, plus DJs Lone Ranger and Michigan and Smiley.

After armed bandits attacked his Brentford Road headquarters, Dodd transferred Studio One to a new base in Brooklyn, New York, where he made sporadic recordings for much of the 1980s and early 1990s, including dancehall works with Frankie Paul and JD Smoothe, sometimes voiced on new mixes of old rhythms. A re-issue programme instigated by Boston’s Heartbeat records also kept his vintage material in focus. In 1991, he received the Order of Distinction, Jamaica’s third highest honour, for his services to the Jamaican music industry. Following the death of his mother, Dodd moved back to Kingston in 1998, to reopen the Brentford Road facility for a further set of new recordings with veterans and young talent alike, while the high-profile reissues and documentary DVD released by London’s Soul Jazz Records brought Studio One’s popularity to an all-time high.

Through it all, Dodd remained an avid lover of music and an astute businessman, with a wry and disarming sense of humour. In recent years, he was plagued by arthritis, which made physical movement difficult, although recent treatment provided some improvement.

In May 2004, Brentford Road was officially re-named Studio One Boulevard by the Kingston municipal authorities — a fitting tribute. Less than a week later, Coxsone Dodd died of a heart attack at his studio, the place where so much Jamaican musical history was made. His wife Norma and six children survive him.

“Don’t be downhearted,” Norma Dodd said to a group of Studio One associates a couple of days after Dodd’s death. “Things will go on, because that is what Mr Dodd would have wanted me to do, and I have to do it.”