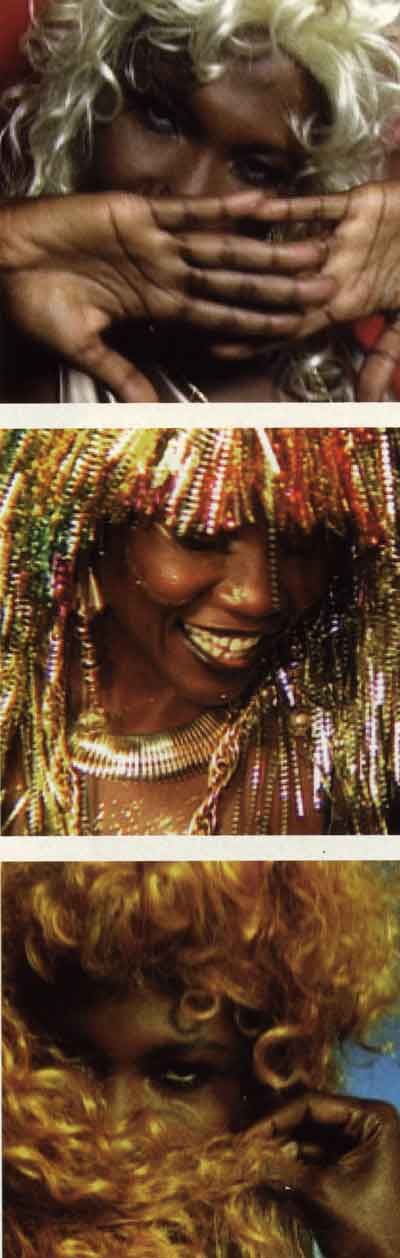

Before the movie, there was Carlene. Chris Salewicz looks at the queen herself and the phenomenon of the aggressive Jamaican divas known as the dancehall queens

Onstage at the African Star club in Kingston is Olivine, the dancehall queen, dressed in satin next-to-nothing. Languorously, she rubs her hands between her legs, grabbing her crotch and squeezing it, her hips humping to the piston-like digital dancehall beat: Olivine makes the hitherto scandalous onstage movements of Madonna look like those of a nun. And this spectacle isn’t confined to the stage. In the audience there is just as much lubricious sensuality in the untrammelled dancing of the onlookers, some going so far as to mime the sex act with their partners.

This, in fact, is a scene from the climax of the film Dancehall Queen, in which the reigning monarch is about to be deposed. But it could be any number of weekly contests, of lesser or greater weight, in Jamaica. The success of the movie, the most popular picture in Jamaica ever (eclipsing even Home Alone 2), is a reflection of what these contests represent: an escape for women from grinding ghetto poverty and a route to a new life. Starring Audrey Reid as Marcia, the street vendor who succeeds in toppling Olivine, the film presents an archetypal scenario. “I know it seems like a Cinderella story, but it’s also the truth of what happens,” said Suzanne Fenn, the film’s writer. “The whole point about the idea of becoming a dancehall queen offers hope, even if it’s only an idea of a way out.”

Dancehall dancing manages by turn to be undilutedly sensual and warmingly funny — as good sex should be, of course. “A night out at a dancehall club can be absolutely hilarious,” said the Dancehall Queen co-director Don Letts. “None of these girls are regarding themselves totally seriously. Or at least the ones who win aren’t. It’s all very much tongue-in-cheek — or wherever,” added his directing partner Rick Elgood.

In the very concept of the dancehall queen, which has become internationally recognised with the relative success of the film, can be read a typically Jamaican twist on female empowerment, replete with the habitual number of paradoxes that seem requisite for most matters on the island. Distinguished academics like the University of the West Indies’s Carolyn Cooper, for example, trace the line from Nanny, the female Maroon chief, to dancehall queen; but others see this heritage as going back no further than to the influence of the island’s raunchy go-go clubs in which tomorrow’s dancehall moves may be seen today (and often much, much more . . . ) and the favours of the dancers are frequently for sale.

“There are links between dancehall fashion and go-go,” said one dancehall queen contest winner. “It’s the same thing: it’s all dancing to Jamaican music. So it comes under the same line. Go-go dancing is something that’s been in Jamaica for years, long before my time. And I think will always be here, even when dancehall is gone. Go-go is not degrading to me because I can accept people for doing what is an honest job. There is little difference between dancehall and go-go: you’re just not paid in a dancehall. We’re both representing reggae music and sexiness.”

Although dancehall queen contests were happening long before Dancehall Queen hit the cinema screens, the success of the film has given a new impetus and urgency to the regular competitions. In the audience at one such contest in Montego Bay was the international boxer Lennox Lewis, there to view a bevy of dancers anxious to let the audience see how long they had spent on their nails, hairstyles and costumes.

“At that contest,” remembered Rick Elgood, “there was some absolutely outrageous dancing — some of them just wound and ground and flashed their pumpums and some of them wore very revealing costumes. But the ones that won weren’t like that. In fact, some of them were very good dancers. There were about 20 contestants, who were cut down to 10 and then to four. The girl that won, a local girl, went on to win another competition, when they had a music convention in Montego Bay. The event itself was very long-winded, starting off with a fashion show, with Stone Love sound system in charge of the music.

“When the girl was crowned it was a major event going on for about half an hour. It was done by an enormous woman who stood in the way with her massive bulk, stopping anyone in the audience seeing what was going on. The girl was in tears, she won something like a thousand US dollars. There was a very big crowd, and the event went on too long. I noticed a lot of grabbing of girls backstage.”

But any dancehall night at Portmore’s Cactus, Liguanea’s Mirage or New Kingston’s Asylum will see an army of wannabe queens, gangs of girls from all over the city letting it all hang out, courtesy of such dancehall designers as Ouch and Lexxus. Lexxus, a fey character with dyed blond hair, plies his designer and tailoring trade from small premises in Half Way Tree that are highly popular with visiting Japanese tourists. “Dancehall fashion comes from an African thing,” he said, as a model demonstrated a dress made of see-through vinyl, the perspiration on her back soon fogging up the material. “And things have gone so far with exposing parts of the body that the next fashion is bound to be pure nakedness.”At any of these clubs you might even find the one and only original dancehall queen herself, the self-titled “Carlene, the Dancehall Queen”. Some — especially Carlene — will claim this very Jamaican cultural phenomenon is all her fault, for it turns out that Carlene’s regal position was not bestowed on her, but created by the woman who would be queen.

In 1986, when Carlene was only 15, she had worn a three-inch mini-skirt whilst out in Kingston, causing traffic chaos in Half Way Tree Road; the phenomenon was even reported on the radio. “I always had it in me to wear little of whatever. I didn’t think of it as rude. I just thought of it as what I like for me.”

But Carlene’s reign did not begin until February 1992. That month, at a fashion clash at Cactus, Carlene’s crew faced a team of four of Jamaica’s top models, including the then Miss Jamaica, all clad in swish evening dress — in contrast to the dancehall styles sported by Carlene and company.

The next day headlines in the press bestowed on her the tag of Carlene the Undisputed Dancehall Queen. “All this came because of my unique designs. It was never a dancehall clash that made me dancehall queen. It was a fashion clash.”

When I called on her at her modern house in Portmore, Carlene the (Undisputed) Dancehall Queen was in character, wearing a one-piece fishnet outfit over a vinyl bra and panties set, and thigh-length boots: as she talked she reclined on a fake zebra-skin that covered her bed. A Bible lay open by the side of it. Downstairs was the dancehall superstar Beenie Man, with whom she has had a well-documented long romance, and some of his crew.

A surprisingly hefty girl, Carlene looks as though she might pack quite a punch. From an uptown background, with a Lebanese father, Carlene started out with a beauty salon in Negril aimed at the tourist trade before graduating to become a designer of dancehall clothes. Needless to say, in relentlessly, troublingly colour-conscious Jamaica her light skin complexion has led to criticisms that that is the main secret of her success: “I am half-white, half-black, but I’m still Jamaican and I consider myself very black, even though I am so clear,” she said. “Wearing a blonde hair is something that I consider sexy. A lot of people said I reigned and got accepted because I am upperclass, very clear-complexioned, and my nose is straight.” There’s more than a hint of pride. “That’s the advantage they think you have over a black girl. Kind of yes. But I worked hard for where I am. I worked hard for what I wanted said and done. If a girl is so clear she doesn’t usually have the body I have: she’ll look more flat-chested, with no bottom.

“I’ve never gone nude. I’ve never exposed my private parts. My buns has been there — that’s part of my assets, my breasts and my bottom. In Jamaica men like that.”

Whatever these complexities of colour, however, Carlene picked up her royal title and ran with it. “Dancehall Queen has become a full-time job for me, because I made it that. I sat and I thought of what I was doing, what I wanted to do. How far I wanted to go, exactly what limit I wanted to reach — all of this.

“People think, ‘Oh, she’s so lucky!’ No, it wasn’t luck. I had fight from the media, from church people, everybody. I decided I was going to fight back. This is why what I’m doing is still alive. I love that people are taking my image and utilising what I do today. It’s been five years that I’m dancehall queen.”

Why did Carlene want this job? What was in it for her, apart from ephemeral stardom? She seems to understand her position as an archetype: “I had to put aside a lot of things that I wanted to do. Because I am living for a lot of people.

“A lot of people out there have put down dancehall as gun-and-violence — and it’s not so. For the kids who look up to me as a role model I want to always let them know that what I do onstage is a job. And that offstage I’m a normal person and that the media has done a lot of injustice. I didn’t know all this was to come with the title Dancehall Queen.”

Stories about dancehall are rarely absent from Jamaica’s press — and are often far more favourable than Carlene suggests. The genre has even spawned its own publications; specifically a pair of weekly tabloids, X News and Hardcore, both filled with scantily-clad girls and newsbite stories.

“There is something about Carlene that defies explanation,” said Milton Williams, publisher of Hardcore. “She has been around for a long time: in dancehall to have any longevity is quite unusual. But she has a certain degree of class and attitude in the way she portrays herself that keeps her popular.”

Needless to say, dancehall’s in-your-face X-rated sexuality hardly fits the view of womanhood as perceived by feminism.

“I say to those people who think what I am doing is sexist,” commented Carlene, “enjoy life for what it is and what you can make life to be. Do not let other people’s happiness be sadness for you. A lot of people look at what I do for encouragement. I know this for sure, especially the ghetto society: I have made girls who would have probably had three or four babies think, ‘Well, I can dance, so I can make something of my life. I don’t have to wait on a man, or think if I don’t have a baby, that’s it for me. Dancehall dancing has gone to the highest level: you have Janet Jackson dancing the Butterfly. So to those people who think it’s sexist, I say, ‘Get a life!’”

But isn’t it sexist just to consider the role of women in dancehall? What about men? “Men are outdoing us sometimes now: men now go out of their way to look good,” said Carlene. “The women of Jamaica also want the men to look good. Jamaican men have become much more fashion-conscious than ever before. They’re going to the gym, they’re bleaching their skin to look cool.”

And how long does Carlene intend to reign for?

“People have tried to dethrone me. I have never had a real challenge to say, ‘Give me this title!’. Because there is no real dancehall queen. I planned this, I started it. When I’m through making this statement I want to make, I will have to give up my title. But I’ll be Carlene the Dancehall Queen for life. I think I’m going to go down in history as the dancehall queen: there is no competition there.”

Presently Carlene is “endorsing” one of Jamaica’s newest products, Slam condoms. “They’re studded, like Rough Riders, but don’t have that rubbery smell,” she explained thoughtfully.

On the television advertisements for Slam, Carlene breathily intones the tag line, “Feel the rhythm, feel the ride.”

It could almost be a high concept one-line summation of the life of Carlene The (Undisputed) Dancehall Queen.