How does the sheltered daughter of a suburban community in Trinidad come to be one of the most decorated principals in Canada? What is it about Sandra Dean that qualifies her to talk to teaching congresses in Norway, Sweden, Egypt, the USA, and persuade the leaders of Grenada that hers is the way to shape a new national education policy?

At first glance, there is a cool inscrutability about her smooth round face. Not plump, but madonna-like. Somebody’s wife — husband Ishwar Dean is Professor of Physics at George Brown College in Ontario. Somebody’s mother — sons Shiva and Rishi are on the thresholds of their own careers. A pout suggests she is accustomed to her own way; headstrong, wilful. Then something sparks her interest, and she smiles: the eyebrows go up; the corners of her eyes disappear; and her mouth is wide, generous.

Sandra Dean has risen from star student in the Ontario Public School system to star principal. Twenty years have passed since she started working on the Durham District School Board in Whitby, Ontario, with the mentally handicapped, and being transformed from one “learning to teach” to one “teaching kids how to learn.” It featured a “change of heart,” and that is what she desires for children today: a change of heart.

Working in special education since the late 70s, Sandra has learned how to help children with special needs. “I taught students to read that they said could never read. I made them authors: reading, writing and reading their own work. I developed the Literary Guild — a programme that now involves all schools.”

She was made vice-principal of a model school in Whitby, Ontario, a brand new school in a new community. The staff were hand-picked; everything that the Board believed in was provided. The children came from happy environments: bright, well-motivated, eager to learn. “It was a totally wonderful experience. And we saw what could happen when everything is in sync for the children.”

Then in September 1991 she was appointed principal of a very different institution, South Simcoe Public School. “It was a school I never wanted to go to. I didn’t see what I could possibly do there. I didn’t see it as a place where I could make any impact. When they phoned me to ask me if I would go there, I asked if they could move me at the first possible opportunity. My superintendent said to me, ‘Sandra, you will shine there. You should go.’ I even went to my director to ask, ‘What did I do wrong. Did I step on somebody’s toes?’ I had been referred to as one of the bright lights on the Board. But the reaction was like, ‘You’ve been lucky to have had that school . . .’ And I went. And struggled in the first few months, because I went with all my ideals, and wanting to do all these things. It was culture shock. I had had a very loving and supportive staff and community. I had never faced any situation like this in my life. That December, my father died, so I figured on top of everything, what else can go wrong?”

By the start of the new year, her relationship with the school had not improved. Sandra made up her mind to quit: not just the school, but the Board, everything. “Ishwar called a friend to talk to me. He’d never seen me like that. Fortunately, I have always been lucky to have mentors, people from whom I could learn. She was very clever. She said to me, ‘What will happen to the children when you leave? There will be no one to fight for them.’

“I couldn’t face that. I took myself in hand, and I stopped feeling sorry for myself. I went back with a different kind of determination. I went back in charge. I wasn’t this nice little girl asking for people to do things. I was the principal. All my training kicked in. Once you’ve decided to be in charge of your life, it changes.” A friend introduced her to another Trinidadian principal, Stephen Ramsankar, working in Edmonton. “I had him come out and speak to my staff. From then on was a turning point. He helped me articulate what I wanted to do.”

In the first year, the changes were slow but gradual. Sandra sought out members of the community, found comfort with teachers who accepted her vision and students who were beginning to learn that “respect” is life’s vital lesson. Respect of self, of fellow man, of all living things, of the order of the universe. “Every human has the right to be respected: that is one of the core beliefs of our programme.” This required teaching teachers how to be respectful to the children; how to teach and to discipline without screaming and yelling.

By the end of the second year, there were others to share her vision. She introduced “sunshine calls” — the first calls that teachers made to parents would be positive, warm, welcoming, so when there was need to speak about helping the child, interaction was more likely to be beneficial. She challenged teachers, parents, students and leaders in the business community: “What does the school stand for?” She reminded them of the old African proverb: It takes a whole village to raise a child.

The youngest child at South Simcoe today will reply, “Respect” — and explain what it means. Teachers and students work out differences through clear, direct dialogue. A younger student said to an older one who was trying in vain to get a game organised, “We don’t scream at kids here . . .” Children have stood up to abusive adults with the words, “You have no right to do this to me, I am a human being . . .” The entire community has understood what the school is doing and has begun to support it.

There are sessions on the “respect” system not only for children, but for teachers, parents and businessmen. “If someone makes a mistake, we don’t leave them with, ‘Don’t do it again!’ but the more positive ‘What will you do next time?’ There’s a reward system too, in which children who have demonstrated respect are served a wonderful lunch by teachers, police, community leaders. They like that. And it’s not just the children, all members of the community are constantly learning.”

“Wonderful Wednesdays” feature informal lunchtime talk-sessions with her staff. “Each member of staff has a responsibility to keep himself up and to lift others who may be down. Even a child at South Simcoe will sometimes approach an older child or adult to raise a glum mood.”

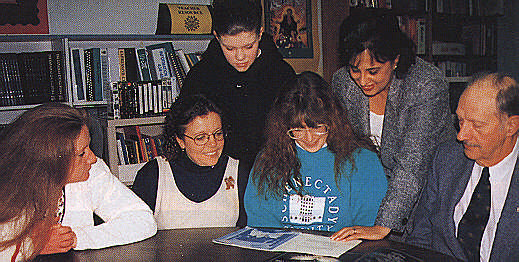

No-one loses sight of academic goals: in testing throughout Ontario, the school has moved from a 20% performance level to above the provincial average. The school is teaching people to learn, and to live, from the deepest spiritual level — with values and respect — and employability is high among the life skills. Business partners in the South Simcoe community are fully committed; visitors move regularly in and out of the classrooms. There is a special spirit here, they report, warm and comforting and generous.

Business partnerships mean that students are not insulated from the realities of the wider society. “By introducing kids to the business world,” says Barry Kuntz, an executive at General Motors, “we are showing them how to improve their position in life. Students learn practical skills and start to see connections between what they learn at school and what happens in the work world.”

The transformation of South Simcoe, and the awards and publicity that followed, might have impressed the Prime Minister of Grenada, Dr Keith Mitchell. But it was Sandra herself that Dr Mitchell signed on to an education programme aimed at “knitting back the fabric of Grenada; bringing everybody to work on the common goal; raising the consciousness of the society; rebuilding from the inside out.”

Sandra is exhilarated by the prospect of working in the Caribbean again. She welcomes the opportunity to build a bridge back to roots. She remembers her sheltered growing-up as the beloved first child of middle class parents: “Things we learned from sitting round the kitchen table, from our grandmothers or Sunday school, are no longer being passed on to children,” she recalls. A Caribbean childhood meant warmth, family, security. To speak with a group of Tobagonian principals two years ago “was like touching home.”

In 1970, when young Trinidad was stirring with political ferment, she completed her first degree at the University of the West Indies at St Augustine, majoring in Sociology and Political Science. A generation later, she returns to the Caribbean from Canada, full of possibility, ready to tackle the challenge for which she believes her whole life has been a preparation: working for children in the Caribbean.

“At all levels of the education system, educators are realising that they have to meet the human resource needs of business, while businesses are realising that they need to take a long-term approach to their country’s economic prosperity by supporting with time and money the structural reforms of the educational system . . .

“One hundred years from now, it will not matter what kind of cars we drove, what kind of houses we lived in, what kind of clothes we wore, nor how much wealth we accumulated. All that will matter is the difference we made in the lives of our children.”

Sandra Dean, address to Prime Minister, educators and members of the business community of Grenada, July 1997