A huge broken caterpillar of bales, boxes and bags twists along the wharf beside a red-hulled ship. Formidable ladies in bright clothes and straw hats loom like exclamation marks amid the confusion. In the dim light, the lamps of the forklifts flicker like vipers’ tongues through the crowd. Horns sound, voices bawl.

Young men bowed under the weight of huge loads stagger up the gangway to deposit their burden in heaps on the ship’s already tightly packed main deck.

The mood is getting tense. There’s still a mountain of goods on the wharf and it’s being added to all the time as pushcarts enter from left and right bearing more cargo. Surely some people and their belongings will have to be left behind?

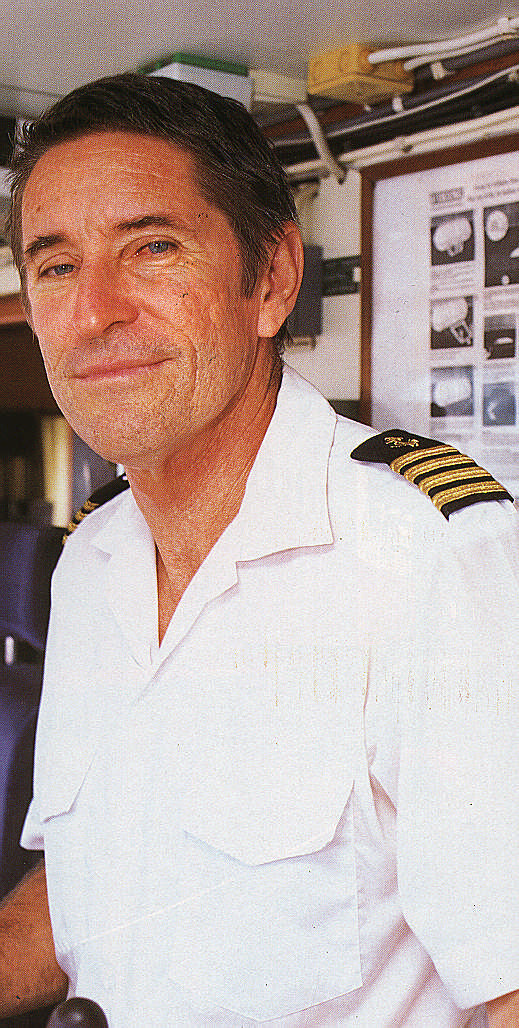

Standing in a state of relative calm in this profusion of disorder is a man in uniform: grey shirt with braid on the shoulders, close-cut hair. He has a boyish face. “Looks like Peter O’Toole,” someone whispers, peering down from the upper deck of the ship.

It’s not O’Toole. This is Tor Torsteinson, owner and captain of the ship, and he’s seen all this before. But right now he might wish this was a movie and he could call “Cut!”, because he’s just conceded that all this cargo may not get on board.

Those big ladies will tear him apart.

But Captain Tor, as he’s known to most of his Caribbean friends, lost none of his appendages that night. In fact, with extraordinary skill and much sweat, the crew of his ship, the M.V. Windward, loaded every last box and bag of yam, ginger, dry coconut and bananas on board before it set sail for Trinidad.

Captain Tor was ebullient. “This will pay US$4,000,” he said. Not bad considering that five years ago, when the Windward’s service was first launched, there were times when it carried only three passengers and one pallet of cargo; in its first year it had a book loss of US$300,000.

The market ladies from St Vincent, to whom the cargo belonged, were among the 28,000 people the Windward now carries annually; they were happy too. They had a comfortable place to rest their heads for the calm overnight passage under a bright starlit sky on a clean, safe, comfortable ship.

And they arrived at their destination on time, their produce intact. The money they’d make from the sale of their produce in Trinidad would purchase goods to resell back in St Vincent, a tidy economic equation which would seem to everyone’s benefit.

Everyone wants to travel with us now,” says Norwegian-born Torsteinson as we approach Trinidad. There are a few light clouds over the Northern Range, the mountains of Venezuela close by in the west, as green as Ireland from the rainy season. The sea is a sparkling mosaic in the morning sunlight. A hammerhead shark has just run across the bow; baby flying-fish scud across the water like showers of hail.

“I just want to establish a good service,” says Captain Tor at the end of his four-hour watch on the bridge. “I look at it as a hobby. It’s fun doing something that has never been done before, although you would think that with all these islands there would have been a good transport service.”

He’s not always as effusive. His work load is excessive, and when he’s not on the bridge he’s hunched over a computer sorting out finances. His wife Yvonne thinks he’s crazy, and he obviously shares her opinion at times.

But the Windward is a success story in West Indian maritime circles, where it’s not unknown for vessels to expire, turn into rotting albatrosses around governments’ necks, or be so poorly maintained that no-one in their right mind would want to travel on them. And as an institution it’s a cheap and slightly offbeat way of travelling around some of the Caribbean islands.

The Windward herself is a stubby child’s version of a ship, with a short funnel that’s just for show — the exhausts are in the stern — and the general appearance of having been assembled from a Lego kit. Although there’s an edge of Nordic efficiency on board, the mood is all Caribbean warmth. Torsteinson is gracious and accommodating to his passengers. The bridge is open to visitors. “People that travel with us are surprisingly easy going,” he says. Maybe it’s their response to the Windward’s good vibes.

For US$158 you can travel from Venezuela to Trinidad, St Vincent, Barbados, St Lucia and back again. Add US$20 a night for a cabin. The food’s extra. “You get to see a bit of local life that you wouldn’t otherwise observe,” says Andreas Bryhn, a 25-year-old Swede travelling to Barbados (“it’s a good party place”) after spending a month in Venezuela.

Theresa Gonzague, who lives in Trinidad, is taking her children, Terry Anne (12) and Ricky (14), on a sentimental trip to St Lucia where she was born. “My father will be there from the US,” she says, holding her daughter tenderly. A Canadian couple, both in safari hats and carrying expensive luggage, travelling from Barbados to St Lucia, chose the Windward simply on the basis of price. “My wife wouldn’t even take a cabin,” says the husband, perched on a bench at the stern rail where the couple spent the night.

The seeds of the Windward were sown in the early sixties when Torsteinson’s father grew tired of his farm in central Norway, bought a 43-foot fishing boat, the Betty Joan, and headed for Martinique with his 17-year-old son. When the fish didn’t bite, Betty Joan sprouted sails and was reincarnated as a budget charter yacht out of Antigua.

Young Torsteinson met and married his wife Yvonne, and together they operated a succession of yachts. In 1972 they bought their first cargo ship, Moruka, followed by Bimiti and Marudi. The stepping-stone to the Windward was the purchase of the ferry boat Admiral, which Torsteinson and partners run with a sister ship between Bequia and St Vincent.

Windward’s purchase from its Norwegian owners was partly financed by a US agricultural loan. Its inspiration was a pair of ships that plied the islands in the late 1950s, the Federal Palm and the Federal Maple, gifts from the Canadian government to the ill-fated West Indian federation. “We run the first ever privately-operated ferry service in the West Indies that’s survived without government subsidies,” Torsteinson says proudly.

Despite its apparent benefits to the region, none of the islands — except St Vincent, where pilot fees have been waived and the ship is registered — give the Captain any concessions. And St Vincent cargo fees are higher than other ports. “They don’t even recognise we’re a ferry with a schedule,” Torsteinson fumes in one port when officials hold him back from departing because they’re late delivering his clearance documents. “Some islands even treat me like a cruise ship and charge for non-island passengers.”

The main financial burden, however, is simply the cost of operating the 33-year-old former Norwegian coastal ferry. It has a crew of 17 and it costs US$12,000 to fill her huge tanks with fuel, although that’s enough to make the Venezuela–St Lucia round trip twice.

On board there’s a duty-free shop that makes a small profit, and a cafeteria that serves food and drinks.

“We haven’t changed our fares and we can’t change them,” says Torsteinson. “We can’t come close to the air fare or we would lose our passengers.”

The sky is overcast, and the Windward is stomping through a swell out of the north-east, heading for Barbados at 13 knots, her two 1,000-horsepower Normo eight-cylinder diesels trumpeting from their stacks at the stern.

“You see that?” says second mate Len Davis, pointing south. Reaching towards the sea out of a dense patch of dark cloud, like a trembling finger, is a waterspout. It is too far away to be any danger on this empty stretch of the ocean; it’s just part of the natural show along the way. In February and March around Bequia, whose waters we sailed through earlier, migrating whales are a common sight.

The Windward is a tourist brochure writer’s dream. It deftly presents the southern Caribbean experience, nature, culture and history in a tidy package. Even the most jaded traveller would be hard pressed not to feel a tremor of excitement or get a whiff of romance arriving by sea in a new country.

It’s the back door approach these days, without the screaming jets and miles of anonymous highway before you reach your destination. Step off the ship, walk a few paces and you are in the heart of the matter. Even after only 12 hours at sea — a strange mix of seduction and being taken hostage — sights and smells on land are heightened.

Because she has to off-load and take on cargo, Windward usually spends several hours in each port. In St Lucia, the most northerly island she sails to, she’s on the wharf in Castries for between 24 and 36 hours, depending on the schedule.

After days of being a hard-working inter-island freighter, Windward briefly becomes a party-boat. Barbadians fill up her cabins on Friday night, when she docks in Bridgetown, then sail west for a weekend of St Lucian fun. “We been dancing, those St Lucia girls are real sweet,” says Michael Hughes, a Bridgetown government worker, after a happy Saturday night in Castries.

On Sunday morning, many of the Barbadian passengers go to church; others hold an impromptu service at the stern of the ship. Officers and crew-members off watch take the Windward’s inflatable dinghy out of Castries harbour to nearby Vigie beach for a game of cricket.

Vigie beach, beside the single-runway airport in Castries, is worth a trip just to meet Rety Graham who runs an alfresco bar and eatery out of coal pots, baskets, boxes and coolers on the beach opposite the airport terminal. People help themselves and help each other. It’s hard not to catch Rety’s enthusiasm as she shrieks at old friends and makes new ones between serving fried fish, chicken, floats, beer, soft drinks and rum, while the wind flaps through the fronds of coconut trees and planes land and take off on the other side of the airport fence.

Back on the Windward, Torsteinson is still catching up on book-keeping.

The vessel’s accounting procedure is computerised but remarkably complex. Alana Weekes, the young Guyanese crew member who operates the ship’s cafeteria, with great aplomb and grace under pressure, has to make change in five currencies: Eastern Caribbean dollars, Barbados dollars, Trinidad and Tobago dollars, Venezuelan bolivars and US dollars. Sterling and Canadian dollars are also accepted on board. Today’s her birthday, and there’s been a party in the crew’s quarters. But she’s back to work tonight. “The crew gets burned out,” says Torsteinson, who wants to implement a better time-off schedule.

He’s just about to close a deal on a new ship, almost twice the size of the Windward, with stabilisers, cabins for 182 passengers, a bar and a restaurant, as well as a cafeteria. He says this will allow better organisation. She will be faster and extend the Windward Lines service further, including calls in Tobago, Martinique, possibly Dominica and Carriacou. There’ll also be a new port of call in Venezuela, closer to Caracas, in addition to Margarita and Guiria which are served now.

The Windward will continue to sail, fares will remain unchanged and passengers will be able to switch from one ship to another. “We have plenty plans,” says Torsteinson, who’s got the backing of a consortium of Norwegian ship-owners for his new vessel. “If we don’t buy a better ship, someone else will and we would lose out. We are going to make it a little more like a cruise ship. We will provide cheap cruises, dirt cheap.”

We’re pulling out of Bridgetown in Barbados, past a US guided-missile cruiser and a British frigate; tied up between them is the white gleaming slab of a cruise ship. This little ship would fit in its swimming pool. But it’s the name of the ship that registers. She’s the Windward too, and Norwegian, owned by Norwegian Cruise Lines. Her passengers are being driven in buses to the gates of the port. They’ll be greeted by eager taxi drivers, guides, hucksters.

Torsteinson’s little dream ship may not be to everyone’s taste. But it’s an alternative to the impersonal floating palaces that ply the Caribbean and the ageing schooners that may or may not carry passengers anyway. The little Windward represents choice, and that can’t be bad.

“Looks like Peter O’Toole,” someone whispers, peering down from the upper deck of the ship

The sea is a sparkling mosaic in the morning sunlight. A hammerhead shark has just run across the bow; baby flying-fish scud across the water like showers of hail.

Although there’s an edge of Nordic efficiency on board, the mood is all Caribbean warmth

“We been dancing, those St Lucia girls are real sweet,” says a Barbados government worker after a happy Saturday night in Castries

She has to make change in five currencies: Eastern Caribbean dollars, Barbados dollars, Trinidad and Tobago dollars, Venezuelan bolivars and US dollars. Sterling and Canadian dollars are also accepted.