The life of an opera singer is not all glamour. The bass baritone Willard White is sitting in a blank hotel room in Liverpool, looking out over a dreary winter’s day. As he talks about his childhood in Jamaica almost 50 years ago, it can seldom have seemed so far away.

The life of an opera singer is a busy one. Last week he was singing in San Francisco; current projects cover Mussorgsky in Brussels, Stravinsky in Paris, Debussy in Amsterdam. Embrace the incessant travel or get out of the business, he says. It’s the price of life at the top of the tree.

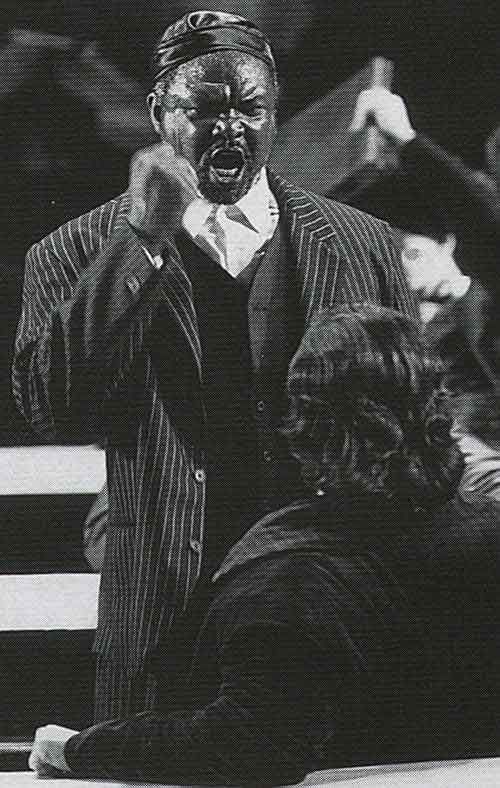

Right now he’s a broadfaced, tranquil man with a graying beard and a leather waistcoat. On stage later, he’ll flame out into violence and madness as the high priest Zaccaria in Verdi’s Nabucco, which might be hard to believe if there weren’t about him a suggestion of underlying force.

“That slowly-moving manner should deceive nobody – inside, the man’s quicksilver brain is working away famously,” the conductor Simon Rattle once said of White. It’s a useful combination in one who has been quite a pathfinder; opera now may have a good handful of black female stars – Jessye Norman, Leontyne price, Barbara Hendricks, Grace Bumbry – but the men are thinner on the ground. There are, says White, still those who think that a black bass equals Ol’ Man River.

Certainly when he started out back in the sixties Willard White was an exotic – which makes his miraculous voice, blooming out of a background with no especial trace of music, seem all the more (he has said like a gift from on high.

The day he first became aware of his voice is one he remembers clearly. “I would have been about 14, and I had been told off by my stepmother, I thought unjustly. I felt greatly injured. In the back of our yard there was a coconut tree. I sat down next to it, stirring myself in a willful fashion into the depths of depression.” He speaks slowly and deliberately.

“I sunk lower and lower, hoping that she would see the effect she was having on my whole personality. To no avail — she was going about her business and so it was up to me. I could stay there with a knot in my stomach, in a fever of self-pity, or I could do something. There was a song I’d heard from Nat King Cole. Smile though your heart is aching, Smile even though it’s breaking. I started to sing it – haltingly at first, then louder and louder, until I was using it like a weapon. That was the first time I really appreciated the power of music. And realised a certain power I had within me.”

His father was a foreman at the Kingston docks, “and a good whistler” he always says, half jokingly, when asked if there wasn’t music in his family. He sang in church, and cousins still in Jamaica remember him going up in the trees and singing from there, or so they told him recently. He sang along to the radio — but that was the music of the Four Tops, Elvis Presley, Bing Crosby, calypso from Trinidad and Jamaican mento. “Classical music I thought a bit boring — the beat wasn’t there.”

Was it the teachers at school who first noticed his remarkable voice? No, the students, he says, remembering vividly. “I’d just gone to high school, and the teacher was doing the register. I was at the back, adopting the retiring attitude which was natural to me. We all had to stand up and say our names, until it got to my turn at the end. Then every head went forward as if something had hit them from behind. One beat, and then prolonged laughter. I didn’t know what it was that made them laugh, but the nicknames soon enlightened me. They called me Thunder, Old Man, Grumbler, Frog, Rumbler. And Bigger — that one stuck.”

White’s voice has always been deep like thunder. “People back off. It still happens today.” Says Trevor Nunn, who directed him in Shakespeare’s Othello: “When he murmurs in a room, it’s immediately noticeable because it’s two octaves lower. People tend to go quiet and say ‘What’s happened? when it’s just Willard asking for a cup of tea.”

The idea of music as a career came only slowly. He wanted to be an economist — it seemed a way to make some difference in the world — and went to work in the office of a food distributor. But colleagues remember him going off to sing in corners at lunchtime, to get his spirits up to face the second half of the day.

He got a scholarship to train part-time at the Jamaica School of Music, and it was then that he was sent to see Lady Barbirolli, wife of the famous conductor Sir John, who was there on tour with the Halle Orchestra.

“I was taken to the Governor’s Residence — we had a governor then. Sir John was having a rest but his wife would come to hear me.” He sang her an aria from Don Carlos he’d picked up by listening over and again to a recording in the school library. Lady Barbirolli was impressed. She wrote a letter of recommendation that Willard should study in London or New York. New York was nearer, the fare was cheaper. The ticket he got was one way.

Growing up in Jamaica, he says, he hardly noticed the beach, the sun, the colours — all the things that tourists want to see. “You take all that for granted.” When he left Jamaica that first time, “I couldn’t wait to get away. But as the plane banked I looked down and I saw the deep green, the various shades, it was like a new world. And tears came to my eyes because of a beauty I’d never seen.

When he got to New York, the culture shock was “enormous”, he says, for the first time using his great voice fully. The weather was one problem. “The first time I experienced five days without sun I thought something terrible was going to happen. In Jamaica it never rained for more than a day, and that was just before a hurricane. Rain was a valid excuse for not going to school.” And he was chronically short of money. He’d arrived with just $200 and got part-time work at a local hospital, wheeling bodies to the morgue.

Race, moreover, was a new issue to deal with. This was the late sixties and a time, as he says, of great tensions. Fellow students met in the streets would sometimes look away. An ongoing factor in his life? In 1972 he met and married his white English wife Gillian, a music teacher from Manchester, and there has been the odd remark when she is out with their five children. But “the world is full of prejudice, whether you’re black or white. I don’t have to dwell on it.”

Professionally, too, there has been the odd controversy. The casting of roles still isn’t always colour-blind. “It depends on who’s doing the casting. The decision they have made about the production, the qualities you embody as a singer.” But his philosophy is one of acceptance, something that goes deeper than mere pragmatism. Something you understand very fast about Willard White is his free-ranging interest in spirituality.

“At the time I embarked on my career, the first thing of all was to accept that the colour is there. I’m not going to make it a problem . . . The best I could do was prepare myself thoroughly, appreciate my differences, believe in what I have.”

He quickly got work with the New York City Opera, then was brought to Britain in 1976 by Lord Harewood on contract for the English National Opera (ENO). But his true breakthrough didn’t come until 10 years later, at Glyndebourne, as Porgy in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. The role of the crippled beggar is a complex one: to help the cast, director Trevor Nunn told them to place the story in their own community.

“I remembered when I used to go to market with my mother, there was a man terribly crippled who would sit on these roller skates and travel by propelling himself along the ground. But he had such dignity.”

Porgy was a triumph for White. From there, Trevor Nunn invited him to play the title role in Shakespeare’s Othello at Stratford three years later. He was the first black singer since Paul Robeson to tackle, not the opera, but the play itself. Another member of the cast gave him advice from Sir Ralph Richardson: stress the last word of every line to get the right bounce. The emotions were more difficult for him. Faced by Othello’s jealous dilemma he himself would walk away (“I hope.”) “A truly towering performance,” wrote theatre critic Jack Tinker reverently.

“Willard works completely from within himself. He doesn’t seem to use any technique, any tricks,” says Michael Grandage, who played Rodrigo in that production. With his six-foot-two height and rolling eye he has a powerful presence, but he works firstly from the character; placing the tone of his voice was something he first understood as a way of making the words interesting, as an end in itself. “You bare your soul when you open your mouth to sing.”

His huge range — one way of arming himself against any scarcity of parts — covers Wagner, Mozart, Verdi, baroque music and oratorio. His voice can stretch from top G right down to low D. He’s sung Wotan in Das Rheingold (though there were letters from Wagnerians complaining that because of his “cultural background” he couldn’t properly portray the god), Osmin in La Seraglio, Colline in La Bohème.

From here, his career should only get better. This sort of voice becomes more mature, more impressive, richer as it goes along. Back in 1976, White bravely bowed out of singing Sarastro in The Magic Flute a week before the opening — it was to have been his ENO debut — saying the voice wasn’t grand enough. He wouldn’t have to worry now.

“It used to be that, gosh, every two years or so my voice made a little shift. Now it’s a shift every day. That’s such a wonderful teacher of relationships, especially the relationship of me to me.”

Artists’ mysteries have a fascination. With so much resting on one single, vulnerable ability, how does a singer protect the voice — from infection, say? Unhysterically, says White. You won’t find him rushing away when anyone sneezes. When he’s not working, he likes to live very ordinarily. Walking or cycling around his South London home, listening to baroque music, or maybe jazz. His chief interest is other people, he says with a kind of unassuming practicality.

He doesn’t get back to Jamaica as much as he’d like. But it remains for him “a particularly vibrant place, in the spirit of the people chiefly.” There is something he learned there that he takes wherever he goes, a blend of confidence, self-reliance and humility.

“A singer’s talent is not just being able to sing. There is a certain nerve there — a courage, you could say. From my upbringing in Jamaica, I learnt that there is blood in me very similar to everyone else, and nobody is better than I am. I learned to reach for whatever I want. To try.”

In New York once, he heard a radio interview with a jazz musician. The interviewer told him how lucky he had been. “Yes, and the harder I work the luckier I get,” the musician replied. Willard White quotes the story approvingly.