You may not know it, but there is more to Grenada than Grenada.

Grenada always tries to outdo the other islands: first woman Governor, first Miss World, first coup in the English-speaking Caribbean. Other countries in the West Indies may have twin-island states: Antigua-Barbuda, St. Kitts-Nevis, Trinidad-Tobago. But we have a tri-island state: Grenada-Carriacou-Petit Martinique. And if anyone attempts to equal that (if St. Kitts ever got Anguilla back, for example) we just might add Isle de Ronde to our state – it does have a population of about forty people!

If you are in Grenada for sufficient time you might try a one-day visit to its sister island, Carriacou. For a few people, one day in Carriacou is too much; they can’t wait to get away. It’s too slow, they complain. But most find that they have been bitten by the island’s offbeat attraction and keep turning up again and again. As they become repeaters, it takes them longer and longer to get the length of Main Street in Hillsborough, the only town, on their first day back. They are continually halted by Carriacouans whom they met before and who show a genuine delight in seeing them again. Many-time returnees may find it takes two mornings to get to the post office and back to their hotel or guest house or cottage, and do alternate sides of the street each morning.

It is possible to visit Carriacou and return to Grenada the same day by LIAT, which has a special rate for this. There are also tours which can be arranged by travel agents and hotels in Grenada. The day includes a sampling of the island’s best known attractions: Windward’s boat building, the Carriacou Museum, and a picnic at Sandy Island.

After breakfast at Hillsborough’s only hotel (you are far too early to get it at your own in Grenada) you may be taken to Windward village on the north-east coast. Across a short stretch of water looms the mountain of Petit Martinique, the third segment of the tri-island state, with a population of about 700.

In Windward live the descendants of Scottish shipwrights who, according to the conflicting opinions of various experts, (a) were brought out by Scottish planters to build their inter-island trading schooners; (b) were transported because of being on the losing side in rebellions in England from the time of Monmouth onward; (c) were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars who were heroes on their first return home but found no jobs awaiting them (shades of World War II veterans!); or (d) were “redlegs” from Barbados who suffered great hardships after the great fire there of 1845. Take your pick: no-one in Windward has as much information as you have now.

All they are sure of is that they are Scots, and their names indicate this: McFarlane, McLawrence, McQuilkin, Davidson, Stewart. A sea captain named Martineau was most astounded to learn that his name was not Scottish.

Their lives are still centered around boats. There is always something being built or careened for repairs. Trading schooners are still one of the best investments in the West Indies. And in Windward the method of building them is much the same as it was two hundred years ago.

If you are very fortunate you may be in Carriacou the day of a launching. The launching of an ocean liner is a poor affair in comparison – a bottle of champagne broken on the bow, a few cocktails, a few sausages on toothpicks. Windward people would scorn such minginess.

Their ship, waiting on the beach, has a goat sacrificed on the bow and a sheep on the stern. The carcasses are quickly removed to the cooking pots, huge kettles like those seen in cartoons of natives boiling missionaries. The deck of the schooner is then filled with little girls dressed in their frilly best – the godmothers of the ship. The priest climbs abroad and, swinging his censer, blesses the ship. Two, religions, in a very civilised manner, have turned a blind eye to each other’s rites. Then the launching begins, with chanting and heaving on ropes. The boat slides into the water and the fête goes on from early to late, with music and eating and drinking.

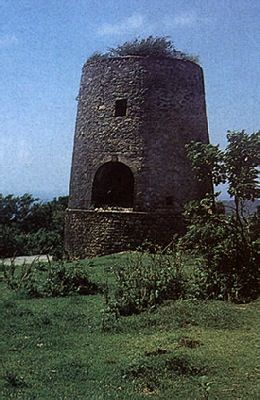

After driving along the central ridge of the island, with its old grey sugar mills, you descend to the town of Hillsborough again.

Your call at the Carriacou Museum may just stretch your mind. The very existence of a museum on an island of five to seven thousand people is a minor miracle. As is the fact that it could happen with no government support, as the Carriacou Historical Society, which owns and operates it, is a completely private organization. Over fifteen years, an Amerindian collection, called by one expert “the most representative in the West Indies”, has been built up. It is in a temporary display, awaiting the funds to complete a permanent exhibit. The European collection includes artefacts illustrating the style of life in a wealthy cotton island where, most unusually, the riches were owned not only by whites but by coloured and black islanders as well. The African display has “big drums” from Carriacou ‘s unique Nation Dances, still little changed from their origins in West Africa, and modern crafts from these countries.

After this a small boat will take you to Sandy Island in Hillsborough Bay. This looks exactly like everyone’s mental picture of a desert island. Around it are reefs with enough colourful fish to satisfy the most jaded snorkeller. If there are enough people on your tour, a chef will grill your fish and chicken on the beach. A combination of rum punches and turquoise sea completely unwinds you.

But if you come to Carriacou on your own for the day, and your time is yours, I have a suggestion. Walk into Hillsborough – it’ s not far. It will be very early, about 6:30 a.m., and deliciously cool. After the exodus of taxis from the airport the road will be very quiet. For the first part there are only palm trees on one side and the sea on the other. Dawn has broken and pinkish clouds float over a hushed seascape. There are few places in the world now where you can have something like this all to yourself.

As the road angles a little inland, you will see people tending their gardens or their sheep and goats. Call “Good morning” and they will answer you with friendliness and an interest in where you’re from. They are a people with family everywhere – in Huddersfield, Brooklyn, Toronto, even Switzerland.

When you come to an almost deserted town, only passing people on their way to mass, your nose may begin to twitch with a most delectable odour. Bread is being baked in old stone ovens over wood embers. You hurry on to the hotel with your stomach crying for breakfast. Inhaling your steaming coffee you look across the morning sea at the islets of Jack a Dan and Sandy and Mabouya, floating, unreal.

And, even though you have only started your day in Carriacou, you may already be hooked.