Lennox Honychurch is as much a part of Dominica as its green, cloud-drenched peaks, rushing streams and crystal waterfalls. When I met him in Dominica’s capital Roseau, we were constantly interrupted by Dominicans wanting to greet him, and to each he responded warmly in creole, asking about their families and recent activities.

Honychurch’s activities are so numerous and so diverse that it’s hard to believe any single person would have the time and the energy for them all. Researcher, historian, author, artist, actor, poet, activist, legislator — this is a man who has made a profound impact on the consciousness and the landscape of his country.

Perhaps the root of it all is the urge towards research and communication: the need to uncover and record, and then to use any medium available to help people see and understand.

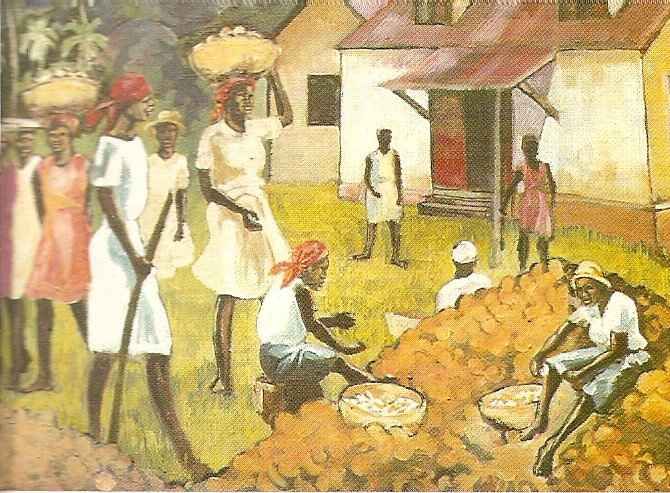

Most visible are his intricate Carnival costumes, many of them celebrating Dominica’s history or environment, and the murals he has painted in Dominica’s churches and public places. His books about Dominican history and culture are well-known, and incorporate his own illustrations and photographs. His poetry is characterised by the most thoughtful and sensitive approach to land and history that any island could hope for.

His books are standard reading for anyone interested in Dominica. In his teens, Lennox Honychurch began writing articles and short stories for the local paper; noticing there was a scarcity of resource materials about the island, he produced a radio series about Dominican history. That provided the basis for his first book The Dominica Story.

Museums are another enthusiasm. A board member and founder of the Museum Association of the Caribbean, Honychurch believes that good museums can transform the Caribbean cliche of sea, sand and sun into a richer, more realistic view. Above all, they must serve Caribbean people – “they should be developed in the first place for the Caribbean people to know and understand their own history.”

But they must influence visitors too. Tourists are encouraged to see the Caribbean as a place where people sing calypso, play steelpans and dance all day, he complains; songs like Yellow Bird, Jamaica Farewell and Island in the Sun perpetuate an image that Caribbean people have grown out of.

“We can provide so much more than that. We can enrich our product and show that we are as diverse and historic as Greece. We can go back over 5,000 years. Our history is bloody, colourful, and tragic. It’s like a Carnival band in many different facets and fabrics.”

This enchantment with Dominica has been lifelong. From childhood, Honychurch was immersed in island life. “My parents took me in the middle of Carnival bands, up into the hills, into little villages dancing quadrilles, exploring here, camping there, swimming over there . . . ”

His family had a keen interest in research. His father was a natural history enthusiast, and his grandmothers wrote articles about Dominica for the local press. His maternal grandmother (the first West Indian woman elected to a legislature) wrote about Dominica and the Caribbean for England’s Manchester Guardian.

His family roots are Caribbean, dating back to the 1790s when the Honychurches of Devon, England, settled in Barbados. The Scottish name Lennox was derived from his grandfather, Lennox Napier, who settled in Dominica with his wife Elma in the 1930s. Other family members came from Trinidad and St Kitts.

Honychurch’s identity is totally Caribbean. Put him in a boat anywhere in the Caribbean sea, and he can tell you the name of each island simply by its outline.

Historic sites in his Caribbean backyard, like Brimstone Hill in St Kitts, Nelson’s Dockyard in Antigua and Pigeon Point in St Lucia, led him towards historic restoration at home. From 1982 to 1990 he researched and supervised the restoration of Fort Shirley, on Dominica’s north-west coast.

This 18th-century British military garrison was built to defend Prince Rupert’s Bay, where ships of the Royal Navy anchored to rest their crews and collect fresh water and provisions. It sits on a 260-acre headland once known as La Pointe de la Cabrits, or “the point of the goat”, because early French sailors would leave goats to run wild there to ensure fresh meat for future visits. In 1986 Cabrits was designated a national park; a cruise ship berth and visitors’ centre have been installed on the site of the old military jetty – it is the only place in the Caribbean where passengers can step off a cruise ship directly into a national park.

Honychurch went to England to unearth and study the fort’s structural plans, and he often located artefacts and buildings that he would later uncover in the tangled jungle. It was a fascinating project, watching the old fort re-emerge from the forgotten past.

But it was not easy. The cannons, weighing two tons each, had to he hauled from the beach to their positions in the fort. Honychurch had the idea of borrowing sailors from a visiting British warship to move the guns (after all, the British navy hauled them up the hill in the first place). The naval attaché was amused by the request, but in the end complied, and the cannons were returned to their old home as they had been in the distant past, by hauling and tying, block and tackle, to the accompaniment of much cursing and drinking of beer.

Honychurch’s powers of persuasion were also used during his association with the Dominica Freedom Party as it rose to power between 1975 and 1980. He helped the party with its publicity and with a new image, coming up with slogans and posters. After the party lost the 1975 election, many members, tired of seven years in opposition, became disillusioned and quit. Looking for new blood, party leader Eugenia Charles proposed the 22-year-old Honychurch as a legislator.

The announcement came a few days before he was consulted. “I was thrown off the deep end,” says Honychurch, “but decided to accept. If I take up something, I go full way in it.”

Because of his knowledge of Caribbean history, particularly the fight for democracy and the vote from the 1920s onward, Honychurch felt duty bound to get involved and help to chart a new course for the country. For the next five years he worked closely with Charles, rejuvenating and building the Freedom Party in its weakest area, communication. He wrote manifestos and news releases for radio. He produced placards and presented slide shows at public meetings.

Honychurch and Charles staged public debates and awareness programmes related to the island’s independence constitution; in 1977 he accompanied Charles to England as a delegate to the constitutional conference. According to Eugenia Charles’s biographer Janet Higbie, they made a curious pair. At 57, (Charles) was now grey-haired and stoutish, wearing sensible shoes and round, black glasses that gave her an owlish look. He was 24, tall, lanky and impetuous, with the manners of a 19th-century aristocrat and the moustache, shaggy hair and bell-bottomed trousers of a 1970s college student.” (Eugenia: The Caribbean’s Iron Lady).

Honychurch’s years as a senator were turbulent; after the Freedom Party’s 1980 victory he worked as Charles’s press secretary and chief aide in her first year of office as Prime Minister.

But then personal tragedy struck. In a politically motivated crime, his parents’ farmhouse was raided and burned, and his father, Edward “Ted” Honychurch, was kidnapped. “Had they planned to destroy a part of Dominica’s heritage, they could not have made a better choice,” he wrote, “for the house was packed with a mass of historical material and artefacts as well as Mrs Honychurch’s copious notes and drawings on the flora and herbal medicines of the Caribbean.”

For months it was hoped that his father would be released. But eventually the truth emerged, that he had been killed while trying to escape during the first night of his capture.

Understandably, Honychurch lost his taste for politics.

Instead, he threw himself with new energy into other work. He became an actor, costume builder and set designer with People’s Action Theatre, an amateur company that performed in Dominica and other islands. “Unfortunately, I always got cast either as the white governor, the white planter, or the priest. But at least they were parts.”

Later there were television opportunities. The first, The Orchid House, based on a novel by the Dominican writer Phyllis Shand Allfrey, was produced in Dominica by a British production company and directed by Trinidadian Horace Ové. “I played the part of a rather devious priest, who attempted to reform members of a old, declining Dominican family.”

The Orchid House took over Roseau for three months. Streets were completely redone to create sets. Traffic was tied up as telephone lines were removed, buildings were repainted and horses and carts appeared on the streets. The production employed plenty of local craftsmen, carpenters, painters and drivers.

In the television docudrama Sargasso, produced by the University of the West Indies and the Caribbean Broadcasting Union, Honychurch played the heroine’s lover. The story was based on the great novel Wide Sargasso Sea by another Dominican, Jean Rhys.

Honychurch’s beloved Dominica continues to be the focus of most of his energy. He has been doing a two-year degree in ethnology and museum studies at Oxford, on a British government scholarship that recognised the value of his work in Dominica. Before leaving, he organised his second illustrated book of poetry, and painted his seventh religious mural, plus another for the Roseau Post Office – A Letter Travels, depicting a postal journey from a Dominican country village to an English relative.

The museum he has been developing for the Carib Indian Territory describes the history of the island’s first settlers. The colourful 500-year history of Caribs in the Lesser Antilles has been presented as a footnote in Caribbean history, says Honychurch. From Grenada to the Virgin Islands, it is a tale of conflict and the annihilation of a whole people.

The sense of being deeply connected with a place, an island, is a wonderful thing, and with Lennox Honychurch it is inescapable. “The land gives you a feeling of strength and security, and when you look at how much it has gone through, you know you can go through it too.” He quotes a poem of fellow Dominican Phyllis Shand Allfrey: “Love for an island is the strongest passion.” “What rings in my mind is that even in death, you’re in the mountain, you’re in the land.

That connectedness with Dominica rings through all his work. Perhaps it is best expressed in the conclusion of his Green Triangles: